![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Internet Crime

This chapter introduces the prevalence of crime committed on the Internet. It utilizes the available studies and reports commissioned by various companies, organizations, and the US government to articulate the Internet crime problem.

Key Words

Internet crime; HTCIA; Norton; Computer Security Institute; Federal Bureau of Investigation; Internet Crime Complaint Center

The Internet is like a giant jellyfish. You can’t step on it. You can’t go around it. You’ve got to get through it.

(John B. Evans, former senior News Corporation executive and pioneer in electronic publishing, 1938–2004)

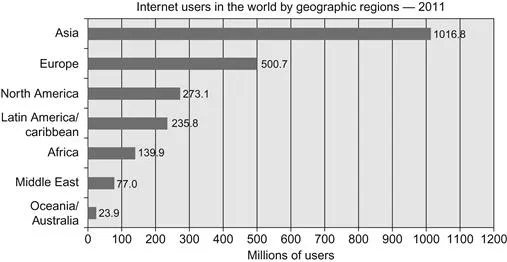

In less then 20 years, the Internet has affected every element of modern society. Worldwide Internet usage increased from almost nothing in 1994 to nearly 2 billion users worldwide at the start of 2012 (Figure 1.1). Seventy-eight percent of North Americans were online in 2011. The current social networking leader, Facebook®, had over 800,000,000 worldwide users on March 31, 2012 (At the time of publishing Facebook according to their website has over one billion users). The Americas alone had over 300 million Facebook® users (Internet World Stats, Usage and Population Statistics, 2012).

Figure 1.1 Internet users in the world by geographical regions—2011. Source: Internet World Stats—www.internetwordstats.com/stat.htm

Internet connectivity is, however, not limited to just humans. In 2008, the number of things connected to the Internet, exceeded the Earth’s human population. Evans (2011) noted “these things are not just smartphones and tablets. They’re everything.” He cites as an example a Dutch start-up company using wireless cattle sensors to report on each cow’s health. Similar medical sensors are being developed for humans. For years many automobiles have been connected to the Internet. By 2020, he notes there will be an estimated 50 billion devices connected to the Internet (Evans, 2011).

Expanding Internet connectivity has been extremely beneficial to many human endeavors, such as communication, education, commerce, transportation, and recreation to name a few. Unfortunately, criminals have also found ways to take advantage of the Internet’s benefits, such as increased opportunities to find and target victims. This translates into a higher likelihood that an Internet crime victim will be walking in the doors of the world’s “brick and mortar” police departments.

Defining Internet crime

Criminal acts on the Internet are as varied as there are crimes to commit. In the Internet’s early years, the notorious criminals were the Kevin Mitnicks1 of the hacker world. Common then was the breaking into phone service and social engineering their way into computer networks. Today hacking has been brought to the masses with the introduction of various “crimeware,” malicious code designed to help the average criminal automate his attacks. But what does the term cybercrime mean? A broad definition would be a criminal offense that has been created or made possible by the advent of technology, or a traditional crime which has been transformed by technology’s use. Internet crimes by definition are crimes committed on or facilitated through the Internet’s use. There is often an over use of the term cybercrime to be all inclusive of many Internet crime categories, including computer intrusion and hacking. Texts have been devoted to the investigation and prevention of computer intrusions and hacking. This book’s primary focus is to provide law enforcement with the basic skills to understand how to investigate traditional crimes committed on the Internet.

Internet crime’s prevalence

Internet crime estimates vary widely depending on the data collection method. Most studies are done through surveying victims and businesses in an attempt to quantify the actual scope of the problem. The Computer Security Institute (CSI) Computer Crime and Security Survey2 solicits information from security experts. Symantec/Norton™ Cybercrime Index interviews individuals on their victimization. The High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA) solicits input from its members, who are made up of law enforcement, corporate, and private investigators, on cybercrime. Other studies look at investigative data, such as Verizon Data Breach Reports. Others collect data concerning specific incidents, such as McAfee Threats Reports, which cover malware3 incidents. Some are concerned with the data collection methods used by many of these studies. After all why would a company selling security products report anything but a high incidence of cybercrime? Normally crime data is collected by law enforcement or criminal justice agencies who presumably do not have a profit motivation.

US crime statistics are reported on a national level by individual law enforcement agencies to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the uniform crime reports (UCR) process. Data is collected on crimes committed by law enforcement agencies under specific guidelines and forwarded to the FBI. The FBI compiles the data and publicly discloses the information in its annual crime reports. Current UCR data collection efforts do not focus on “high-tech” offenses, such as hacking and computer intrusions. There is a hesitancy by some to report cybercrime to the authorities. Publicly traded companies are reluctant to supply information on cyber-incidents fearing such disclosures will damage their image, negatively affect stock prices and/or spark lawsuits (Lardner, 2012).

The reporting requirements also do not mandate the reporting of any information about crimes committed on the Internet or whether a computer was used in the offense. Goodman (2001) points out that those traditional offenses may be classified under something that does not reflect the presence of a computer or Internet use. For instance, an Internet fraud scheme might be classified as a simple fraud. Additionally, cyberstalking might be classified as a criminal threat offense or stalking case.

One ironic data twist concerns sexual enticement cases. These cases are frequently undercover sting operations, in which the suspect believes he4 is communicating via the Internet with a minor. In reality there is no minor. The suspect makes online sexual comments, including his desire to have sex with the fictitious minor. The suspect is arrested when he goes to meet the “minor.” This crime is likely to be classified as sex crime even though there is no real minor or even victim. This is not to minimize the offense’s seriousness or to argue that it should not be counted as sex offense. The computer element and Internet use in this type of offense is clearly apparent and is largely being ignored in the data collection. It is an Internet-based crime but classified as a sex crime where no victim ever existed. This lack of clarity can have important implications for officers attempting to secure resources and training to properly investigate Internet crime.

It is also possible to look to media reports on cybercrime. The important caveat is that such reports tend to focus on the sensational and may not be representative of the vast majority of cybercrime cases. A case may make the headlines because it was novel or was particularly heinous, harmful, or otherwise “newsworthy.” Such crimes may have been isolated incidents and not the norm.

The above realities make it difficult but not impossible to determine the scope of the Internet crime. We obviously can’t definitively state the exact number of Internet crime victims, their actual loss, or even how many possible online criminals are preying on our citizens. We can, however, get a broad outline of Internet crime’s prevalence in our society by examining numerous data sources.

CSI 2010/2011 Computer Crime and Security Survey

The CSI has been a leading educational membership organization for information security professionals for over 30 years. Their study involves sending surveys by post and email to security practitioners. In the 2011, CSI sent out 5,412 such surveys to its members with a total of 351 returns or a 6.3% response rate. The survey looked at the period June 2009 to June 2010. Some of the major findings were as follows:

• Approximately 67% noted malware infections continued to be the most commonly seen attack;

• Almost half the respondents experienced at least one security incident. Slightly more than 45% of these respondents indicated they had been the subject of at least one targeted attack;

• Slightly more than 8% reported financial fraud incidents, which was down compared to previous years;

• At the same time fewer respondents than ever were willing to share specific information about dollar losses suffered (CSI, 2011).

Norton™ Cybercrime Report 20115

Symantec provides information security solutions including software, commonly referred to as Norton™ anti-virus and anti-spyware. Symantec under the trade name Norton™, surveyed a total of 19,636 individuals in 24 countries6 from February 6, 2011 to March 14, 2011. The survey participants included 12,704 adults (including 2,956 parents), 4,553 children (aged 8–17), and 2,379 teachers (of students aged 8–17). Participants were asked if they ever experienced one or more of the following: a computer virus or malware appearing on their computer; responding to a phishing7 message thinking it was a legitimate request; online harassment; someone hacking into their social networking profile and impersonating them; an online approach by sexual predators; responding to online scams; experiencing online credit card fraud or identity theft; responding to a smishing8 message or any other type of cybercrime on their cell/mobile phone or computer. The survey found that more than a million individuals become a cybercrime victim every day. Fourteen adults become a cybecrime victim every second. The top three cybercrimes were computer viruses/malware (58%), online scams (11%), and phishing (10%). Ten percent of the online adults indicated that they experienced cybercrime on their mobile phone (Symantec, 2011).

The Norton™ study also did some data extrapolation and determined the financial losses due to cybercrime to be $114 billion annually. Additionally, they estimated the dollar figure for time individuals lost due to their victimization to be $274 billion. They combined these two amounts for an annual global cybercrime cost of $388 billion. They further noted that this cost was more than the combined global black market in marijuana, cocaine, and heroin ($288 billion) (Symantec, 2011).

HTCIA 2011 Report on Cybercrime Investigation

HTCIA is the largest worldwide organization dedicated to the advancement of training, education, and information sharing between law enforcement and corporat...