- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Thermal Design of Nuclear Reactors

About this book

Thermal Design of Nuclear Reactors

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Summary of Reactor Physics

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the basic principles of reactor physics. It is difficult to understand the need for many components of a nuclear power plant without some appreciation of the way in which the release of nuclear energy is achieved. The source of the heat that is produced in a nuclear power plant is fission. The only naturally occurring isotope that is capable of a self-sustaining fission reaction is uranium-235. In addition to the fission reaction, there are three other types of reactions that are important. The first type is elastic scattering, in which the neutron simply bounces off the nucleus. Total kinetic energy is conserved, which means that the neutron loses kinetic energy. All isotopes exhibit this form of scattering; therefore, the neutrons that escape any other type of reaction steadily slow down. The second type of reaction is inelastic scattering, which is significant in U238 at energies over about 0.1 MeV. The neutron is absorbed to form a U239 nucleus, which immediately reverts to U238 giving out a neutron and a γ-ray. The net effect is that much of the kinetic energy of the neutron is lost to the γ-ray. The third type of reaction is capture, where an isotope of one higher mass number is formed.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter briefly summarises the basic principles of reactor physics. It is difficult to understand the need for many of the components of a nuclear power plant without some appreciation of the way in which the release of nuclear energy is achieved. More detailed information can be found in textbooks on reactor physics, e.g. [1,2].

FISSION

The source of the heat that is produced in a nuclear power plant is fission, i.e. the splitting of a large atom into two smaller atoms. The only naturally occurring isotope that is capable of a self-sustaining fission reaction is uranium-235. One possible reaction when this isotope is bombarded by neutrons is as follows:

The superscripts in this equation are the mass numbers of the various isotopes, i.e. the number of nucleons (neutrons plus protons) in the nucleus. The subscripts are the atomic numbers, i.e. the number of protons in the nucleus, or the number of positive electrical charges. In nuclear reactions the number of nucleons is conserved and electrical charge is conserved.

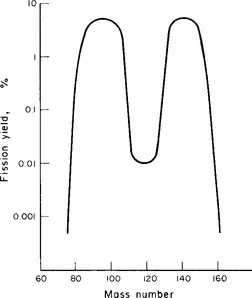

Equation (1.1) is only one of many possible U235 fission reactions. The first step is always the formation of a compound nucleus of uranium-236. This immediately splits into two smaller nuclei plus two or three neutrons. As shown in Figure 1.1 there are a large number of possible fission products. The fission products are radioactive, having too many neutrons in the nucleus for stability, and in a few cases decay after a time of the order of a few seconds by emitting a neutron. The usual decay mode is to give out beta particles and gamma rays, i.e. a neutron in the nucleus turns into a proton plus an electron, and the electron (or β-particle) is ejected at high velocity. The β-emitters have half-lives ranging from seconds to years.

Fig. 1.1 Yield of the different fission products as a function of their mass number. Each fission produces two fission product nuclei, that tend to be of unequal size.

The two most important features of the fission reaction are the fact that more neutrons are produced than were required to initiate the reaction, and the large amount of energy released. On average 2.43 neutrons are produced per U235 fission, so there is the possibility of a self-sustaining chain reaction, at any rate in pure U235 (natural uranium is 0.7% U235 and the rest U238). The total energy released per fission is about 200 MeV and the neutrons produced in fission have an average kinetic energy of about 2 MeV. These quantities are related to SI units by

The distribution of this energy release in time and space is important, and the first step is to know how the energy is divided among the various particles. There are a number of extra points to note. Firstly, the particles produced in equation (1.1) are accompanied by γ-rays emitted instantaneously in fission. Secondly, there are other particles, antineutrinos, given off in association with β-decay. These go straight through the concrete shielding of the reactor, taking their energy with them. They contribute nothing to the heat output of the reactor, and will be ignored in what follows. Thirdly, some of the neutrons in the reactor are captured by other nuclei and do not undergo fission. A small amount of energy is released in the capture reaction, and more later if the new isotope is radioactive. This energy is not produced directly in fission, but must be taken into account in estimating the total heat output. The energy associated with each type of particle is given in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1

ENERGY RELEASED PER THERMAL FISSION OF U235 [3]

| MeV | % | |

| Kinetic energy of fission products | 166.2 | 82.4 |

| Kinetic energy of neutrons | 4.8 | 2.4 |

| Initial γ-rays | 8.0 | 4.0 |

| ²-particles | 7.0 | 3.5 |

| γ-rays associated with β-decay | 7.2 | 3.6 |

| Capture of neutrons | 8.8 | 4.4 |

| Total | 202.0 | 100 |

The distance that the fission products and the β-particles travel in giving up their energy is short, so all their energy will appear as internal energy in the uranium fuel elements, i.e. the initial kinetic energy is converted to the random energy of movement of the individual atoms in the fuel. The fast neutrons and γ-rays have a range of several cm or more. The core is the region of the reactor containing the fuel, and there must in practice be other materials apart from uranium present, so the energy of the neutrons and γ-rays may appear anywhere in the core. However, the fuel elements are very massive, and most of the remaining energy will end up in the fuel as well. So perhaps 95% of the thermal energy will appear in the fuel, and 5% elsewhere in the core, the precise figures depending on the detailed design.

The next problem is what happens when the reactor is shut down. About 7% of the energy released is associated with the decay of the fission products. This will continue after the fission reactions have ceased, and there is no way of stopping it. While the 7% figure only applies for the first second or two heat will continue to be produced at a lower level indefinitely (equation (7.12)). The cooling system must therefore be capable of operating at a reduced level even when the reactor is shut down and no fission is taking place.

The value of 202.0 MeV for the total energy produced has an erro...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Other Titles of Interest

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Summary of Reactor Physics

- Chapter 2: Reactor Systems

- Chapter 3: Fuel-Rod Design

- Chapter 4: Forced-Convection Heat Transfer

- Chapter 5: Boiling Heat Transfer

- Chapter 6: Fluid Flow

- Chapter 7: Safety Analysis

- Chapter 8: Core Thermohydraulic Design

- Chapter 9: Steam Cycles

- Chapter 10: Fusion Reactors

- Notation

- APPENDIX 1: Temperature Distribution Following Sudden Total Loss of Cooling

- APPENDIX 2: Properties of Coolants

- APPENDIX 3: Conversion Factors

- APPENDIX 4: Answers to Selected Problems

- APPENDIX 5

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Thermal Design of Nuclear Reactors by R. H. S. Winterton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemical & Biochemical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.