eBook - ePub

Process Intensification

Engineering for Efficiency, Sustainability and Flexibility

- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Process Intensification

Engineering for Efficiency, Sustainability and Flexibility

About this book

Process Intensification: Engineering for Efficiency, Sustainability and Flexibility is the first book to provide a practical working guide to understanding process intensification (PI) and developing successful PI solutions and applications in chemical process, civil, environmental, energy, pharmaceutical, biological, and biochemical systems.

Process intensification is a chemical and process design approach that leads to substantially smaller, cleaner, safer, and more energy efficient process technology. It improves process flexibility, product quality, speed to market and inherent safety, with a reduced environmental footprint.

This book represents a valuable resource for engineers working with leading-edge process technologies, and those involved research and development of chemical, process, environmental, pharmaceutical, and bioscience systems.

- No other reference covers both the technology and application of PI, addressing fundamentals, industry applications, and including a development and implementation guide

- Covers hot and high growth topics, including emission prevention, sustainable design, and pinch analysis

- World-class authors: Colin Ramshaw pioneered PI at ICI and is widely credited as the father of the technology

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

A Brief History of Process Intensification

Objectives in this Chapter

The objectives of this chapter are to summarise the historical development of process intensification, chronologically and in terms of the sectors and unit operations to which it has been applied.

1.1 Introduction

Those undertaking a literature search using the phrase ‘process intensification’ will find a substantial database covering the process industries, enhanced heat transfer and, not surprisingly, agriculture. For those outside specialist engineering fields, ‘intensification’ is commonly associated with the increases in productivity in the farming of poultry, cattle and crops where, of course, massive increases in yield for a given area of land can be achieved. The types of intensification being discussed in this book are implemented in a different manner, but have the same outcome.

The historical aspects of heat and mass transfer enhancement, or intensification, are of interest for many reasons. We can examine some processes that were intensified some decades before the phrase ‘process intensification’ became common in process engineering (particularly chemical) literature. Some used electric fields, others employed centrifugal forces. The use of rotation to intensify heat and mass transfer has, as we will see, become one of the most spectacular tools in the armoury of the plant engineer in several unit operations, ranging from reactors to separators. However, it was in the area of heat transfer – in particular, two-phase operation – that rotation was first exploited in industrial plants. The rotating boiler is an interesting starting point, and rotation forms the essence of process intensification (PI) within this chapter, with interesting newly revealed data on the HiGee test plant installed at ICI, (Web 3, 2012).

It is, however, worth highlighting one or two early references to intensification that have interesting connections with current developments. One of the earliest references to intensification of processes was in a paper published in the US in 1925 (Wightman et al., 1925). The research carried out by Eastman Kodak in the US was directed at image intensification: increasing the ‘developability’ of latent images on plates by a substantial amount. This was implemented using a small addition of hydrogen peroxide to the developing solution.

T.L. Winnington (1999), in a review of rotating process systems, reported work at Eastman Kodak by Hickman (1936) on the use of spinning discs to generate thin films as the basis of high-grade plastic films (UK Patent, 1936). The later Hickman still, alluded to in the discussion on separators later in this chapter, was another invention of his. Application of PI in the image reproduction area was brought right into the 21st century by the activity reported in 2007 at Fujifilm Imaging Colorants Ltd in Grangemouth, Scotland, where a small continuous three-reactor intensified process has replaced a very large ‘stirred pot’ in the production of an inkjet colorant used in inkjet printer cartridges. The outcome was production of 1 kg/h from a lab-scale unit costing £15,000, whereas a conventional reactor for this application would have required a 60 m3 vessel costing £millions (Web 1, 2007).

In the period between the first and second editions of this book, much of the emphasis on PI has become concentrated in Continental Europe, China and Taiwan. In particular, active intensification methods, particularly using rotating packed beds (see Chapters 5 and 6), have blossomed in the Far East, with organisations such as the Beijing University of Chemical Technology continuing to lead the way with its dedicated ‘Research Center for High Gravity Engineering & Technology’ (Chen, 2009) – see also section 1.4.

Within Europe, the Delft Skyline Debates represent to date the most ambitious attempt to focus PI on meeting the challenges facing humanity. In a special issue of a journal reporting on the outcomes, Professors Andrzej Górak and Andrzej Stankiewicz described how the debates have attempted to define a ‘set of key technological achievements’ that will contribute to sustainability in 2050 and beyond. The areas that the 75 experts within the team addressed were health, transport, living, and food and agriculture (Górak and Stankiewicz, 2012). Aspects of this are discussed in Chapter 2.

1.2 Rotating boilers

One of the earliest uses of HiGee forces in modern day engineering plant was in boilers. There are obvious advantages of using rotation plant in spacecraft, as they create an artificial gravity field where none existed before, see for example, Reay and Kew (2006). However, one of the first references to rotating boilers arises in German documentation cited as a result of post-Second World War interrogations of German gas turbine engineers, where the design was used in conjunction with gas and steam turbines (Anon, 1932, 1946).

1.2.1 The rotating boiler/turbine concept

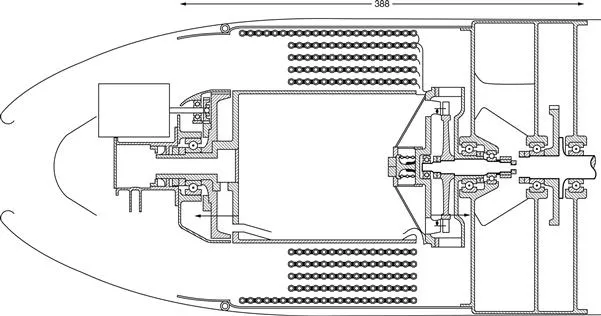

The advantages claimed by the German researchers on behalf of the rotating boiler were that it offered the possibility of constructing an economic power plant of compact dimensions and low weight. No feed pump or feed water regulator were required, the centrifugal action of the water automatically taking care of the feed water supply. Potential applications cited for the boiler were small electric generators, peak load generating plant (linked to a small steam turbine), and as a starting motor for gas turbines, etc. A rotating boiler/gas turbine assembly using H2 and O2 combustion was also studied for use in torpedoes. The system in this latter role is illustrated in Figure 1.1. The boiler tubes are located at the outer periphery of the unit, and a contra-rotating integral steam turbine drives both the boiler and the power shaft (it was suggested that start-up needed an electric motor.)

Figure 1.1 The German 20 h.p. starting motor concept with a rotating tubular boiler (tubes are shown in cross section).

The greatest problem affecting the design was the necessity to maintain dynamic balance of the rotor assembly while the tubes were subject to combined stress and temperature deformations. Even achieving a static ‘cold’ balance with such a tubular arrangement was difficult, if not impossible, at the time.

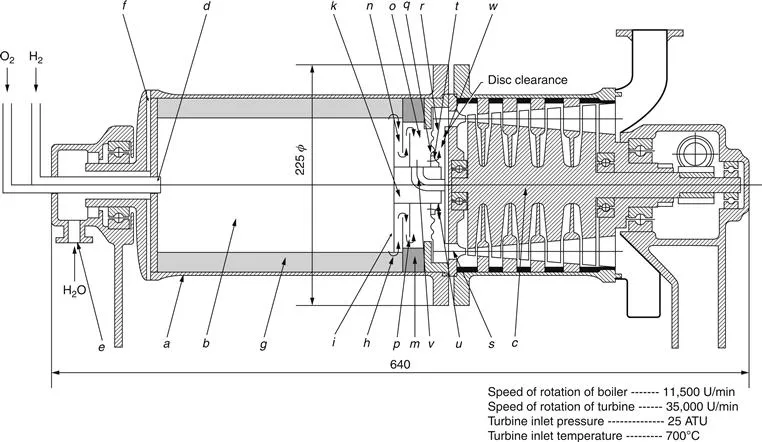

During the Second World War, new rotating boiler projects did not use tubes, but instead went for heating surfaces in two areas: a rotating cylindrical surface which formed the inner part of the furnace, and the rotating blades themselves – rather like the NASA concept described below. In fact, the stator blades were also used as heat sources, superheating the steam after it had been generated in the rotating boiler. One of the later variants of the gas turbine design is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 One of the final designs of the gas turbine with rotary boiler (located at the outer periphery of the straight cylindrical section).

Steam pressures reached about 100 bar, and among the practical aspects appreciated at the time was fouling of the passages inside the blades (2 mm diameter) due to deposits left by evaporating feed water. It was even suggested that a high temperature organic fluid (diphenyl/diphenyl oxide – UK trade name, Thermex) be used instead of water. An alternative was to use uncooled porcelain blades, with the steam being raised only in the rotating boiler.

1.2.2 NASA work on rotating boilers

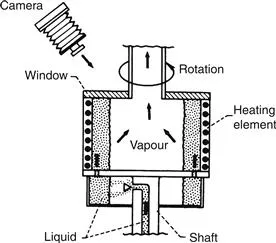

As with the German design above, the first work on rotating boilers by NASA in the US concentrated on cylindrical units, as illustrated in Figure 1.3. The context in which these developments were initiated was the US space programme. In spacecraft it is necessary to overcome the effect of zero gravity in a number of areas that it adversely affects, and these include heat and mass transfer. The rotating boiler is often discussed in papers dealing with heat pipes, which also have a role to play in spacecraft, in particular rotating heat pipes (Gray, 1969; Gray et al., 1968; Reay et al., 2006).

Figure 1.3 Schematic diagram of the experimental NASA rotating boiler.

The tests by NASA showed that high centrifugal accelerations produced smooth, stable interfaces between liquid and vapour during boiling of water at one bar, with heat fluxes up to 2570 kW/m2 (257 W/cm2) and accelerations up to 400 g and beyond. Boiler exit vapour quality was over 99% in all the experiments. The boiling heat transfer coefficients at ‘high g’ were found to be about the same as those at 1 g, but the critical heat flux did increase, the above figure being well below the critical value. Gray calculated that a 5 cm diamet...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. A Brief History of Process Intensification

- Chapter 2. Process Intensification – An Overview

- Chapter 3. The Mechanisms Involved in Process Intensification

- Chapter 4. Compact and Micro-heat Exchangers

- Chapter 5. Reactors

- Chapter 6. Intensification of Separation Processes

- Chapter 7. Intensified Mixing

- Chapter 8. Application Areas – Petrochemicals and Fine Chemicals

- Chapter 9. Application Areas – Offshore Processing

- Chapter 10. Application Areas – Miscellaneous Process Industries

- Chapter 11. Application Areas – the Built Environment, Electronics, and the Home

- Chapter 12. Specifying, Manufacturing and Operating PI Plant

- Appendix 1. Abbreviations Used

- Appendix 2. Nomenclature

- Appendix 3. Equipment Suppliers

- Appendix 4. R&D Organisations, Consultants and Miscellaneous Groups Active in PI

- Appendix 5. A Selection of Other Useful Contact Points, Including Networks and Websites

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Process Intensification by David Reay,Colin Ramshaw,Adam Harvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technologie et ingénierie & Ingénierie de la chimie et de la biochimie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.