Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases

- 444 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases

About this book

Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases provides an overview of oxidative stress in neurological diseases and associated conditions, including behavioral aspects and the potentially therapeutic usage of natural antioxidants in the diet. The processes within the science of oxidative stress are described in concert with other processes, such as apoptosis, cell signaling, and receptor mediated responses. This approach recognizes that diseases are often multifactorial and oxidative stress is a single component of this. The book examines basic processes of oxidative stress—from molecular biology to whole organs—relative to cellular defense systems, and across a range of neurological diseases.Sections discuss antioxidants in foods, including plants and components of the diet, examining the underlying mechanisms associated with therapeutic potential and clinical applications. Although some of this material is exploratory or preclinical, it can provide the framework for further in-depth analysis or studies via well-designed clinical trials or the analysis of pathways, mechanisms, and components in order to devise new therapeutic strategies. Very often oxidative stress is a feature of neurological disease and associated conditions which either centers on or around molecular and cellular processes. Oxidative stress can also arise due to nutritional imbalance during a spectrum of timeframes before the onset of disease or during its development.- Offers an overview of oxidative stress from molecular biology to whole organs- Discusses the potentially therapeutic usage of natural antioxidants in the patient diet- Provides the framework for further in-depth analysis or studies of potential treatments

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenic pathways of depression

Abstract

Keywords

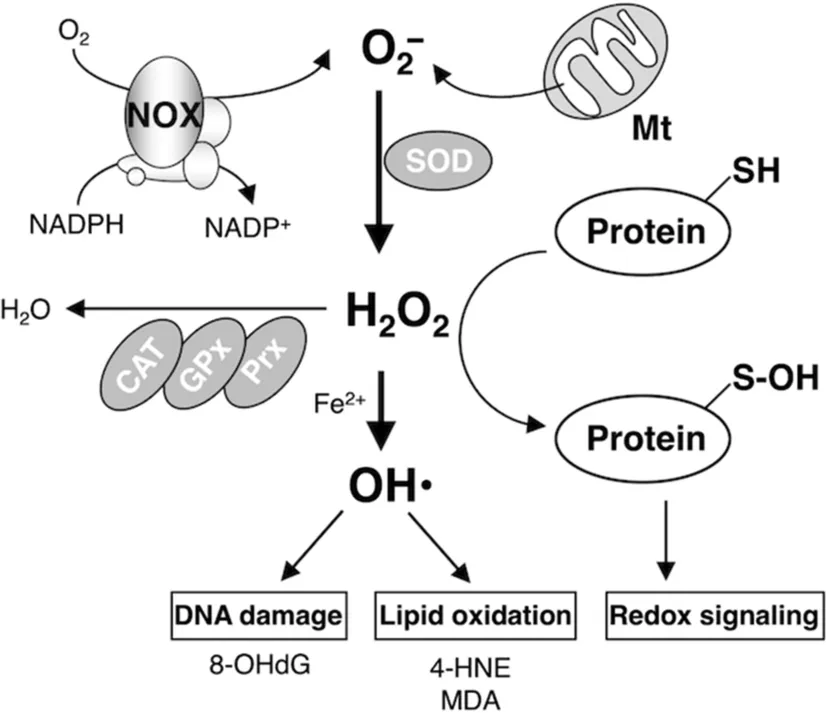

Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant proteins

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part I: Oxidative stress and neurological diseases

- Part II: Antioxidants and neurological diseases

- Index