- 530 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Unraveling Environmental Disasters

About this book

Unraveling Environmental Disasters provides scientific explanations of the most threatening current and future environmental disasters, including an analysis of ways that the disaster could have been prevented and how the risk of similar disasters can be minimized in the future.- Named a 2014 Outstanding Academic Title by the American Library Association's Choice publication- Treats disasters as complex systems- Provides predictions based upon sound science, such as what the buildup of certain radiant gases in the troposphere will do, or what will happen if current transoceanic crude oil transport continues- Considers the impact of human systems on environmental disasters

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unraveling Environmental Disasters by Daniel A. Vallero,Trevor Letcher,Trevor M. Letcher in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780123973177Chapter 1

Failure

This chapter introduces the application of failure analysis to disasters. It identifies five types of failure that can lead to environmental problems: miscalculations, extraordinary natural circumstances, critical path, negligence, and inaccurate prediction of contingencies. These failures are considered from the perspectives of risk and reliability. The various definitions and types of environmental disasters are described, including both anthropogenic (human-caused) and natural disasters. The disasters in Love Canal, New York; Bhopal, India; and Seveso, Italy are introduced as examples of failure analysis. They will be explored in greater detail in later chapters.

Keywords: Disaster, Failure analysis, Environmental release, Events, Risk, Reliability, Hazard rate, Failure density, Bayesian belief network, Critical path, Anthropogenic, Plume, Systems engineering, Methyl isocyanate, Dioxin

A common feature of all environmental disasters is that they have a cause-effect component. Something happens and, as a result, harm follows. The “something” can be described an event, but more often as a series of events. A slight change in one of the steps in this series can be the difference between the status quo and a disaster. Such a series may occur immediately (e.g., someone forgetting to open a valve), or after some years (e.g., the corrosion of pipe), or may be the result of a series of events that occur over decades (buildup up of halocarbons in the stratosphere that destroy parts of the ozone layer).

The mass media and even the scientific communities often treat environmental disasters as “black swan events.”1 That is, even though we may observe a rare event, our scientific understanding argues that it does not exist. Obviously, the disasters occurred, so we need to characterize the events that led to them. Extending the metaphor, we as scientists cannot pretend that all swans are white, once we have observed a black swan. A solitary black swan or a unique disaster “undoes” the scientific underpinning that the disaster could not occur. That said, there must be a logic model that can be developed for every disaster and that model may be useful in predicting future disasters.

Some disasters result from mistakes, mishaps, or even misdeeds. Some are initiated from natural events; although as civilizations have developed, even natural events are affected greatly by human decisions and activities. For example, an earthquake or hurricane of equal magnitude would cause much less damage to the environment and human well-being 1000 years ago than today. There are exponentially more people, more structures, and more development in sensitive habitats now than then. This growth is commensurate with increased vulnerability.

Scientists and engineers apply established principles and concepts to solve problems (e.g., soil physics to build levees, chemistry to manufacture products, biology to adapt bacteria and fungi to treat wastes, and physics and biology to restore wetlands). We also use them as indicators of damage (e.g., physics to determine radiation dose, chemistry to measure water and air pollution, biology to assess habitat destruction using algal blooms, species diversity, and abundance of top predators and other so-called sentry species). Such scientific indicators can serve as our “canaries in the coal mine” to give us early warning about stresses to ecosystems and public health problems. Arguably most important, these physical, chemical, and biological indicators can be end points in themselves. We want just the right amount and types of electromagnetic radiation (e.g., visible light), but we want to prevent skin from exposure to other wavelengths (e.g., ultraviolet light). We want nitrogen and phosphorus for our crops, but must remove it from surface waters (eutrophication). We do not want to lose endangered species, but we want to eliminate pathogenic microbes.

Scientists strive to understand and add to the knowledge of nature.2 Engineers have devoted entire lifetimes to ascertaining how a specific scientific or mathematical principle should be applied to a given event (e.g., why compound X evaporates more quickly, while compound Z under the same conditions remains on the surface). After we know why something does or does not occur, we can use it to prevent disasters (e.g., choosing the right materials and designing a ship hull correctly) as well as to respond to disasters after they occur. For example, compound X may not be as problematic in a spill as compound Z if the latter does not evaporate in a reasonable time, but compound X may be very dangerous if it is toxic and people nearby are breathing air that it has contaminated. Also, these factors drive the actions of first responders like the fire departments. The release of volatile compound X may call for an immediate evacuation of human beings; whereas a spill of compound Z may be a bigger problem for fish and wildlife (it stays in the ocean or lake and makes contact with plants and animals).

This is certainly one aspect of applying knowledge to protect human health and the environment, but is not nearly enough when it comes to disaster preparedness and response. Disaster characterization and prevention calls for extrapolation. Scientists develop and use models to go beyond limited measurements in time and space. They can also fill in the blanks between measurement locations (actually “interpolations”). So, they can assign values of important scientific features and extend the meaning. For example, if sound methods and appropriate statistics are applied appropriately, measuring the amount of crude oil on a small number of marine animals after a spill can be used to explain much about the extent of an oil spill’s impact on whole populations of organisms being threatened or already harmed. Models can even predict how the environment will change with time (e.g., is the oil likely to be broken down by microbes and, if so, how fast?). Such prediction is often very complex and fraught with uncertainty. Missions of government agencies, such as the Office of Homeland Security, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the U.S. Public Health Service, devote considerable effort in just getting the science right. Universities and research institutes are collectively adding to the knowledge base to improve the science and engineering that underpins the physical principles that underpin public health and environmental consequences from contaminants, whether these be intentional or by happenstance.

Beyond the physical sciences is the need to assess the “anthropogenic” factors that lead to a disaster. Scientists often use the term anthropogenic (anthropo denotes human and genic denotes origin) to distinguish human factors from natural or biological factors of an event, taking into account all of the factors that society imposes down to the things that drive an individual or group. For example, anthropogenic factors may include the factors that led to a ship captain’s failure to control his ship properly. However, it must also include why the fail-safe mechanisms were not triggered. These failures are often driven by combinations of anthropogenic and physical factors, for example, a release valve may have rusted shut or the alarm’s quartz mechanism failed because of a power outage, but there is also an arguably more important human failure in each. For example, one common theme in many disasters is that the safety procedures are often adequate in and of themselves, but the implementation of these procedures was insufficient. Often, failures have shown that the safety manuals and data sheets were properly written and available and contingency plans were adequate, but the workforce was not properly trained and inspectors failed in at least some crucial aspects of their jobs, leading to horrible consequences.

Events

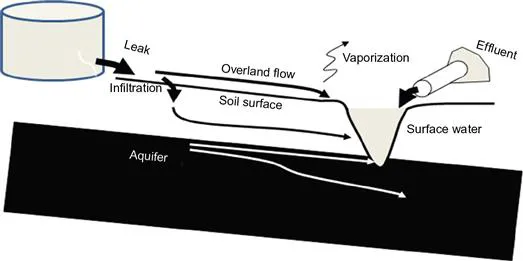

Usually, the event itself or the environmental consequences of that event involve something hazardous being released into the environment (Figure 1.1). Such releases go by a number of names. In hazardous waste programs, such as the Leaking Underground Storage Tank program, contaminant intrusions into groundwater are called “leaks.” In fact, underground tanks are often required to have leak detection systems and alarms. In solid waste programs, such as landfill regulations, the intrusion may go by the name “leachate.” Landfills often are required to have leachate collection systems to protect adjacent aquifers and surface waters. Spills are generally liquid releases that occur suddenly, such as an oil spill. Air releases that occur suddenly are called leaks, such as chlorine (Cl2) or natural gas leak. For clarity, this book considers such air releases to be “plumes.”

Figure 1.1 Contaminants from environmental releases may reach environmental compartments directly or indirectly. Pollutants from a leak may be direct to surface or ground water or indirect after flowing above or below the surface before reaching water or soil. They may even reach the atmosphere if they evaporate, and may subsequently contaminate surface and groundwater after deposition (e.g., from rain or on aerosols).

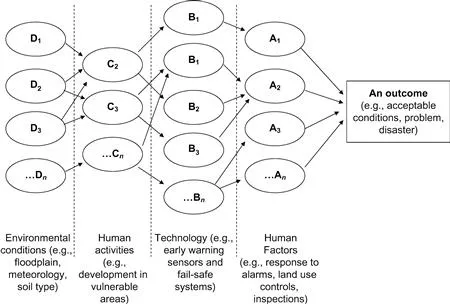

Thus, predicting or deconstructing a disaster is an exercise in contingencies. One thing leads to another. Any outcome is the result of a series of interconnected events. The outcome can be good, such as improved food supply or better air quality. The outcome can be bad, such as that of a natural or anthropogenic disaster (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Bayesian belief network showing interrelationships of events that may lead to a disaster. For example, if D1 is a series of storm events that saturate soils, coupled with housing developments near floodplains and loss of water-bearing wetlands upstream, this could lead to a disaster. However, the disaster could be avoided, at least the likelihood of loss of life and property, with flood control systems and warning systems (B1 and B2). Further, if dikes and levees are properly inspected (A1), the likelihood of disaster is lessened. Conversely, other contingencies of events would increase the likelihood and severity of a disaster [e.g., D3 may be a 500-year storm; coupled with an additional human activity like additions of impervious pavement (B3); coupled with failure of a dike (C3); coupled with improper dike inspections (D4)].

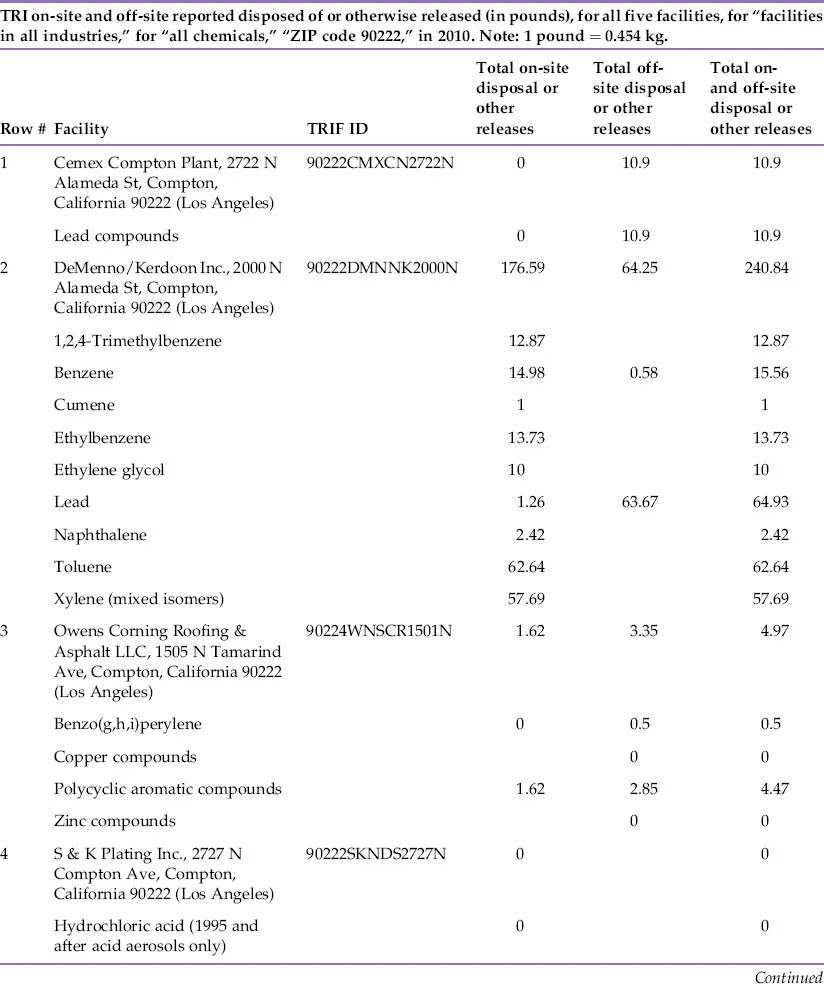

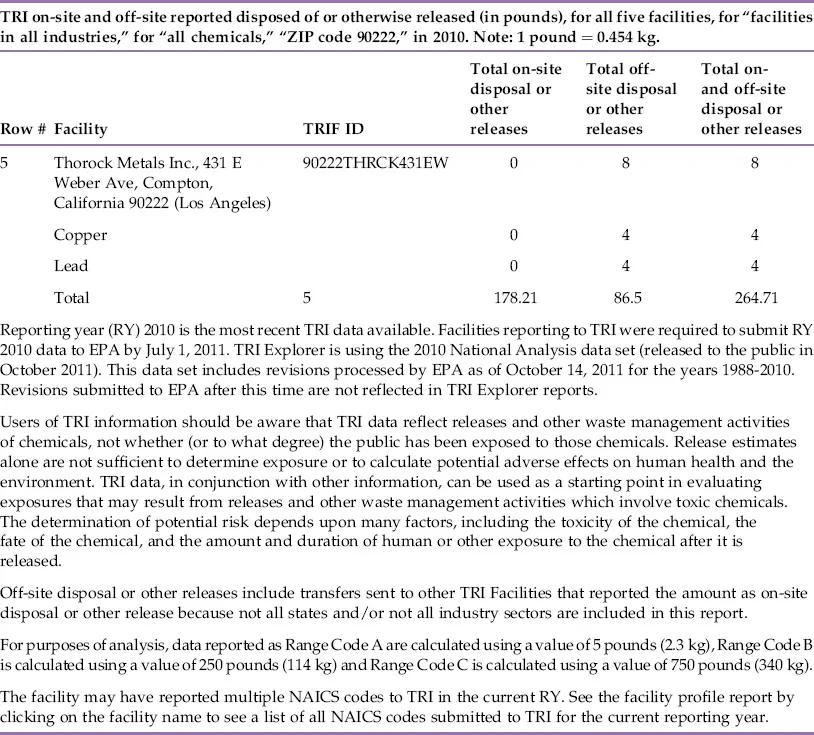

The general term for expected and unplanned environmental releases is just that, that is, “releases,” such as those reported in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI).3 This Web-based database contains data on releases of over 650 toxic chemicals from U.S. facilities. It also includes information on the way that these facilities manage those chemicals, for example, not merely treatment but also more proactive approaches like recycling and energy recover. The database is intended to inform local communities, by allowing them to prepare reports on the chemicals released in or near their communities (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Toxic Release Inventory Report for Los Angeles, CA, Zip Code (90222)

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. http://iaspub.epa.gov/triexplorer/release_fac?zipcode=90222&p_view=ZPFA&trilib=TRIQ1&sort=_VIEW_&sort_fmt=1&state=&city=&spc=&zipsrch=yes&chemical=All+chemicals&industry=ALL&year=2010&tab_rpt=1&fld=TRIID&fld=RELLBY&fld=TSFDSP; 2012 [accessed February 23, 2012].

Disasters as Failures

From a scientific and engineering perspective, disasters are failures, albeit very large ones. One thing fails. This failure leads to another failure. The failure cascade continues until it reaches catastrophic magnitude and extent. Some failures occur because of human error. Some because of human activities that make a system more vulnerable. Some failures occur in spite of valiant human interventions. Some are worsened by human ignorance. Some result from hubris and lack of respect for the powers of nature. Some result from forces beyond the control of any engineering design, no matter the size and ingenuity.

Engineers and other scientists loathe failure. But, all designs fail at some point in time and under certain conditions. So what distinguishes failure from a design that has lasted through an acceptable life? And what distinguishes a disaster from any other failure? We will propose answers shortly. However, we cannot objectively and scientifically consider disasters without first defining our terms. In fact, one important rule of technical professions, particularly engineering and medicine, is that communications be clear.

Reliability

Good engineering requires technical competence, of course. But, it also requires that the engineers be open and transparent. Every design must be scientifically sound and all assumptions clearly ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Failure

- Chapter 2. Science

- Chapter 3. Explosions

- Chapter 4. Plumes

- Chapter 5. Leaks

- Chapter 6. Spills

- Chapter 7. Fires

- Chapter 8. Climate

- Chapter 9. Nature

- Chapter 10. Minerals

- Chapter 11. Recalcitrance

- Chapter 12. Radiation

- Chapter 13. Invasions

- Chapter 14. Products

- Chapter 15. Unsustainability

- Chapter 16. Society

- Chapter 17. Future

- Glossary of Terms

- Index