Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses about spray combustion as a source of energy. The combustion of sprays of liquid fuels is of considerable technological importance to a diversity of applications ranging from steam raising, furnaces, space heating, and diesel engines to space rockets. Because of the importance of these applications, spray combustion alone is responsible for a considerable proportion of the total energy requirements of the world. Spray combustion is a powerful method of burning relatively involatile liquid fuels; indeed it remains the major way of burning heavy fuel oils even at present, though they can be burned in fluidized bed combustors. The basic process involved is the disintegration or atomization of the liquid fuel to produce a spray of small droplets to increase the surface area so that the rates of heat and mass transfer during combustion are greatly enhanced. A burning spray differs from a premixed, combustible gaseous system in that it is not uniform in composition. The fuel is present in the form of discrete liquid droplets which may have a range of sizes and they may move in different directions with different velocities to that of the main stream of gas. This lack of uniformity in the unburnt mixture results in the irregularities in the propagation of the flame through the spray and thus the combustion zone is geometrically poorly defined.

1.1 The General Nature of Spray Combustion

The combustion of sprays of liquid fuels is of considerable technological importance to a diversity of applications ranging from steam raising, furnaces, space heating, diesel engines to space rockets. Because of the importance of these applications spray combustion alone is responsible for a considerable proportion of the total energy requirements of the world, this being about 25% in 1988.

Spray combustion was first used in the 1880’s as a powerful method of burning relatively involatile liquid fuels, indeed it remains the major way of burning heavy fuel oils today even though they can now be burned in fluidised bed combustors. The basic process involved is the disintegration or atomisation of the liquid fuel to produce a spray of small droplets in order to increase the surface area so that the rates of heat and mass transfer during combustion are greatly enhanced. Thus the atomisation of a 1 cm diameter droplet of liquid into droplets of 100 μm diameter produces 106 droplets and increases the surface area by a factor of 10,000.

A burning spray differs from a premixed, combustible gaseous system in that it is not uniform in composition. The fuel is present in the form of discrete liquid droplets which may have a range of sizes and they may move in different directions with different velocities to that of the main stream of gas. This lack of uniformity in the unburnt mixture results in irregularities in the propagation of the flame through the spray and thus the combustion zone is geometrically poorly defined.

Flames used in industrial applications are highly complex systems because of various complicating factors such as the complex flow and mixing pattern in the combustor chamber, heat transfer during the combustion process, and the non-uniform size of the spray droplets. For purposes of demonstration the assumption is often made that the system is uni-dimensional. Thus the flame can be considered as a flowing reaction system in which the properties of flow, temperature, etc. vary only in the direction of flow and are constant in any cross section perpendicular to the direction of flow.

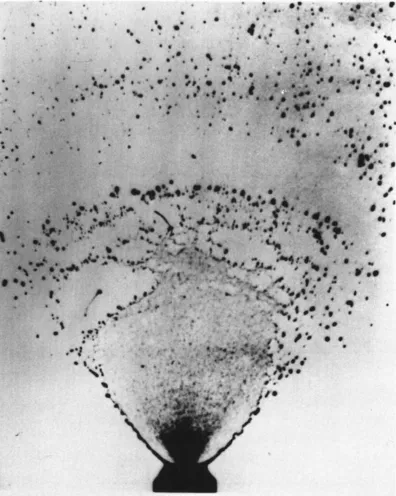

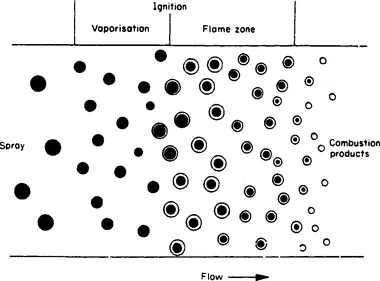

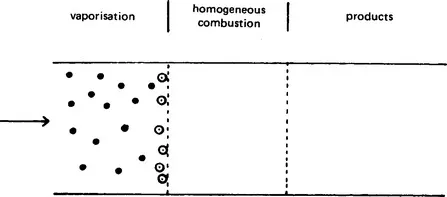

The general nature of the processes involved in spray combustion in such an idealised case for the combustion of a dilute spray is shown in Figure 1.1. Such systems, containing droplet diffusion flames are characterised by their yellow nature. In this one-dimensional case the individual droplets that make up the spray burn as discrete droplets in a surrounding oxidising atmosphere which is most commonly air. This heterogeneous spray combustion is also clearly shown in Plate 1.1 which shows a simplified (flat) spray system. This plate also demonstrates the other major features of a spray flame, namely atomisation, air entrainment, flame stabilisation and the irregular nature of atomisation. The flame front is visible as a diffuse zone across the upper part of the plate. Sprays can also burn in what is effectively a homogeneous way in that the droplets can evaporate as they approach the flame zone so that in fact clouds of fuel vapour are actually burning rather than droplets. This is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1.2. Such flames are characterised by their blue colour and are usually associated with sprays of volatile fuels (such as aviation kerosine) which have small initial droplet diameters (e.g. 10 μm).

Plate 1.1 The essential features of a burning spray. This particular spray flame is produced by means of a fan jet atomiser.

Figure 1.1 A diagrammatic model of idealised heterogeneous spray combustion.

Figure 1.2 A diagrammatic model of idealised homogeneous spray combustion.

It is clear that for any detailed understanding of the process of spray combustion it is necessary to have an adequate knowledge of the combustion of the individual droplets that make up the spray so that a burning spray may be regarded as an ensemble of individual burning or evaporating particles. However it is also necessary to have a statistical description of the droplets that make up the spray with regard to droplet size and distribution in space.

The essential stages involved in spray combustion are outlined in Figure 1.3. The fuel is transmitted from the fuel storage tank by a fuel handling sys...