- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Transdermal Drug Delivery: Concepts and Application provides comprehensive background knowledge and documents the most recent advances made in the field of transdermal drug delivery. It provides comprehensive and updated information regarding most technologies and formulation strategies used for transdermal drug delivery. There has been recent growth in the number of research articles, reviews, and other types of publications in the field of transdermal drug delivery. Research in this area is active both in the academic and industry settings. Ironically, only about 40 transdermal products with distinct active pharmaceutical ingredients are in the market indicating that more needs to be done to chronicle recent advances made in this area and to elucidate the mechanisms involved. This book will be helpful to researchers in the pharmaceutical and biotechnological industries as well as academics and graduate students working in the field of transdermal drug delivery and professionals working in the field of regulatory affairs focusing on topical and transdermal drug delivery systems. Researchers in the cosmetic and cosmeceutical industries, as well as those in chemical and biological engineering, will also find this book useful.

- Captures the most recent advancements and challenges in the field of transdermal drug delivery

- Covers both passive and active transdermal drug delivery strategies

- Explores a selection of state-of-the-art transdermal drug delivery systems

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transdermal Drug Delivery by Kevin Ita in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmaceutical, Biotechnology & Healthcare Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Transcutaneous drug administration

Abstract

The first part of this chapter focuses on the benefits and limitations of transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDSs). Advantages include convenience, avoidance of presystemic metabolism (first-pass effect) and painlessness. Other benefits include noninvasiveness (or minimal invasiveness in the case of microneedles), the absence of gastric irritation, a more uniform absorption, as well as a faster onset of action. One of the limitations of the transdermal route is that externally introduced chemicals (including medications) have to overcome the stratum corneum before entering into systemic circulation. All drugs currently marketed in the form of TDDSs are very potent and typically, their molecular weights are lower than 500 Daltons. Proteins, peptides, and genes are hydrophilic, electrically charged macromolecules and therefore cannot cross the human skin in therapeutic quantities.

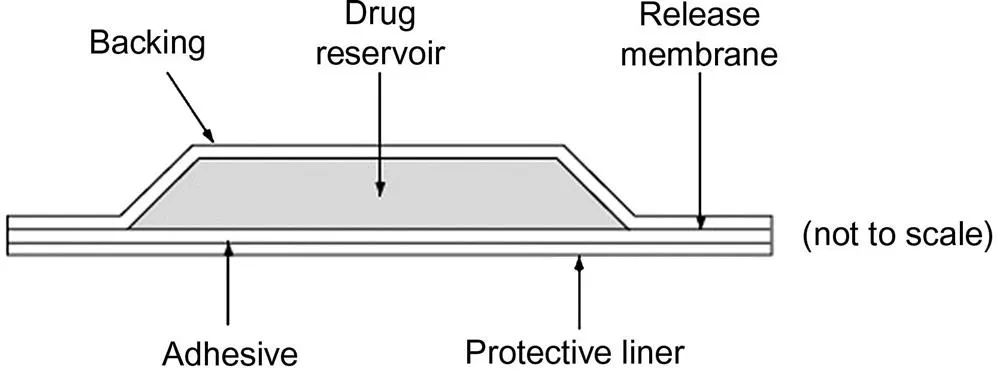

The second part of this chapter examines the classification of transdermal patches. Passive transdermal systems belong to three major categories: the reservoir (membrane-controlled), matrix without a rate-controlling membrane, and matrix systems with a rate-controlling membrane. In reservoir transdermal systems, drug flux depends on the diffusion rate across a polymer membrane. In a matrix transdermal system, the medication is incorporated into an adhesive polymer, from which the medication diffuses through the skin into the bloodstream.

Keywords

Transdermal; drug delivery; benefits of transdermal patches; passive transdermal systems; reservoir systems; matrix systems

Over the last few decades, it has been asserted that the transdermal route of drug administration represents an attractive approach in comparison to oral or parenteral drug delivery [1–3]. Delivering medications through the skin is important because it circumvents presystemic metabolism (first-pass effect), which is typically observed with the oral route. First-pass effect can lead to low bioavailability, adverse secondary effects, and uncomfortable drug dosing schedules [4]. Bacterial enzymes, gut wall enzymes, gastrointestinal lumen enzymes, and hepatic enzymes have all been implicated in the first-pass effect [5]. Recent experimental evidence has demonstrated the utility of transcutaneous drug transport in bypassing the first-pass effect, avoiding intestinal degradation, and providing transcutaneous permeation at controlled rates [6,7]. Percutaneous drug transport is also useful from a pharmacotherapeutic standpoint because there is no pain during drug administration, patients can self-administer, there is no chance of disease transmission by needle sharing, and a slow drug release can be achieved [8]. Transdermal drug delivery can provide effective blood levels for drugs [9]. A drug initially diffuses across the stratum corneum (SC), enters into the viable epidermis/dermis, and then becomes available for systemic absorption through dermal blood capillaries [10]. Transcutaneous drug administration is beneficial in comparison with the traditional administration routes such as oral or parenteral injections due to a number of factors: the oral route is characterized by partial drug absorption, gastrointestinal irritation, and slow onset of action, while hypodermic injections are invasive and painful, generates medical waste, pose risks of infection, and requires administration by medically trained professionals [11]. In contrast, transcutaneous drug administration is painless, noninvasive [12], or minimally invasive (in the case of transdermal microneedles). In addition, percutaneous drug administration usually requires a lower dosage of medications than oral administration due to a shorter diffusional length required to reach the vasculature [13]. Another advantage is the avoidance of side effects caused by erratic absorption and metabolism of the drug in the gastrointestinal tract [13]. Furthermore, transdermal therapeutic systems can be easily applied to the skin, are well accepted, and are relevant options when oral drug delivery is challenging (instances of coma or difficulty in swallowing) [9]. From an economic standpoint, it has been calculated that the global transdermal drug delivery market will grow to approximately $95.57 billion by the year 2025 [14]. The global transdermal drug delivery market is worth $32 billion [15].

The human skin, an organ that receives one-third of the total blood supplied throughout the body, was not used as a drug delivery route for systemic administration until the late 20th century [14]. Scopolamine-loaded transdermal patch was the first commercial patch, and it was approved for clinical use in 1979 [16]. After nearly 40 years of extensive transdermal drug delivery research, only 22 active pharmaceutical ingredients have been approved by regulatory authorities in the United States in the form of transdermal patches [12]. Only low molecular weight, low-dose, lipophilic medications can be developed into transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDSs) with a good chance of therapeutic efficacy and regulatory approval [4,17]. In addition, the daily dose of most approved transdermal medications is typically in the milligram range [4]. Another point worthy of emphasis is that skin sensitivity varies among patients and therefore it is difficult to predict the effect of a transdermal patch. Also, skin occlusion with a patch may induce erythema at the administration site [4]. Furthermore, some medications are intrinsically irritating and early investigation of such compounds should be undertaken early enough in the transdermal drug development [4].

The skin functions as an effective barrier that hinders the ingress of harmful substances from the environment and the efflux of body fluid [18]. This barrier function is ascribed to the intercellular lipids present in the outermost layer of the skin called the SC. One of the obvious limitations of the transdermal route is that externally introduced chemicals (including medications) have to overcome the SC before entering into the bloodstream [19]. The successful transcutaneous permeation of a drug is a function of the partition coefficient (1–3), molecular weight (<500 Da), and the potency of the drug [19]. Equally important is the water solubility of the drug which should preferably be more than 1 mg/mL with the dose being less than 1 mg per day [7]. It is not surprising that all drugs commercially available in the form of TDDSs are very potent and typically, their molecular weights are lower than 500 Da [9]. Even after the drug successfully crosses the SC, it may be degraded prematurely by epidermal enzymes, leading to a reduced bioavailability [13].

From the standpoint of pharmacotherapy, this is an obvious disadvantage as proteins, peptides, and genes are hydrophilic, electrically charged, or large molecules and therefore cannot cross the skin in therapeutic quantities [20]. Various techniques have been utilized over the years to surmount the barrier presented by the SC. Vesicles (elastic liposomes, ethosomes, etc.), chemical penetration enhancers, iontophoresis, sonophoresis, microneedles, electroporation, and other techniques have been used to overcome the SC barrier and increase transdermal drug delivery. The terms TDDSs, transdermal therapeutic systems, and transdermal patches can be used interchangeably. There are two major classes of TDDS: those that are based on passive delivery and those that are based on microneedles, electroporation, sonophoresis, or other physical methods.

Passive transdermal therapeutic systems

There has been a surge in the utilization of transdermal drug therapeutic systems over the past 40 years. The first generation of transdermal delivery systems focused on medications that traversed the skin through passive diffusion [16,21]. Scopolamine-loaded adhesive transdermal therapeutic system was given the FDA approval in 1979 for the management of kinetosis [22]. Subsequently, nitroglycerin patch was approved in 1981 and the nicotine TDDS in 1991 [22]. Developments in science and technology have enabled the utilization of mild electric current (iontophoresis), ultrasound (sonophoresis), and chemical penetration enhancers for enhanced transport of drug molecules that cannot be transported across the skin in therapeutic amounts via passive diffusion alone [16,21]. Third generation transdermal therapeutic systems utilize microscopic needles (microneedles) for transport of medications including high molecular weight agents [16,21]. These TDDSs breach the SC facilitating the transport of the drug molecules [16,21].

Passive transdermal systems belong to three major categories: the reservoir (membrane-controlled) [23], matrix without a rate-controlling membrane [22,24], and matrix systems with a rate-controlling membrane [7,24,25]. A schematic representation of a reservoir transdermal system is shown in Fig. 1.1.

Reservoir systems depend on the transport of the drug out of or through a nonporous or microporous polymer layer [26]. Diffusion through the membrane or the static aqueous diffusion layer may determine the rate of transport [26]. It is important to note that molecular mass and pore size also have significant effect on the diffusion coefficient [26]. In reservoir transdermal systems, the permeation rate is a function of the rate-determining polymer membrane [22]. An adhesive, a rate-c...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- Chapter 1. Transcutaneous drug administration

- Chapter 2. Anatomy of the human skin

- Chapter 3. Basic principles of transdermal drug delivery

- Chapter 4. Elastic liposomes and other vesicles

- Chapter 5. Chemical permeation enhancers

- Chapter 6. Microemulsions

- Chapter 7. Prodrugs

- Chapter 8. Microneedles

- Chapter 9. Iontophoresis, magnetophoresis, and electroporation

- Chapter 10. Sonophoresis

- Chapter 11. Laser and other ablation technologies

- Chapter 12. Mathematical modeling of transdermal drug delivery

- Index