Particle Technology and Engineering

An Engineer's Guide to Particles and Powders: Fundamentals and Computational Approaches

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Particle Technology and Engineering

An Engineer's Guide to Particles and Powders: Fundamentals and Computational Approaches

About this book

Particle Technology and Engineering presents the basic knowledge and fundamental concepts that are needed by engineers dealing with particles and powders. The book provides a comprehensive reference and introduction to the topic, ranging from single particle characterization to bulk powder properties, from particle-particle interaction to particle-fluid interaction, from fundamental mechanics to advanced computational mechanics for particle and powder systems.The content focuses on fundamental concepts, mechanistic analysis and computational approaches. The first six chapters present basic information on properties of single particles and powder systems and their characterisation (covering the fundamental characteristics of bulk solids (powders) and building an understanding of density, surface area, porosity, and flow), as well as particle-fluid interactions, gas-solid and liquid-solid systems, with applications in fluidization and pneumatic conveying. The last four chapters have an emphasis on the mechanics of particle and powder systems, including the mechanical behaviour of powder systems during storage and flow, contact mechanics of particles, discrete element methods for modelling particle systems, and finite element methods for analysing powder systems.This thorough guide is beneficial to undergraduates in chemical and other types of engineering, to chemical and process engineers in industry, and early stage researchers. It also provides a reference to experienced researchers on mathematical and mechanistic analysis of particulate systems, and on advanced computational methods.- Provides a simple introduction to core topics in particle technology: characterisation of particles and powders: interaction between particles, gases and liquids; and some useful examples of gas-solid and liquid-solid systems- Introduces the principles and applications of two useful computational approaches: discrete element modelling and finite element modelling- Enables engineers to build their knowledge and skills and to enhance their mechanistic understanding of particulate systems

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction

Abstract

Keywords

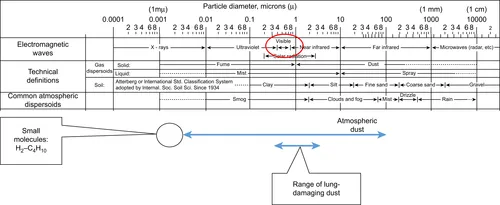

Collective behavior; Discrete element; Particle technology; Particulate products; Predictive relationship1.1. What Are Particles?

1.2. What Is Known?

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Bulk Solid Characterization

- Chapter 3. Particle Characterization

- Chapter 4. Particles in Fluids

- Chapter 5. Gas–Solid Systems

- Chapter 6. Liquid–Solid Systems

- Chapter 7. Mechanics of Bulk Solids

- Chapter 8. Particle–Particle Interaction

- Chapter 9. Discrete Element Methods

- Chapter 10. Finite Element Modeling

- Index