eBook - ePub

Psychology and Climate Change

Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychology and Climate Change

Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses

About this book

Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses organizes and summarizes recent psychological research that relates to the issue of climate change. The book covers topics such as how people perceive and respond to climate change, how people understand and communicate about the issue, how it impacts individuals and communities, particularly vulnerable communities, and how individuals and communities can best prepare for and mitigate negative climate change impacts. It addresses the topic at multiple scales, from individuals to close social networks and communities. Further, it considers the role of social diversity in shaping vulnerability and reactions to climate change.

Psychology and Climate Change describes the implications of psychological processes such as perceptions and motivations (e.g., risk perception, motivated cognition, denial), emotional responses, group identities, mental health and well-being, sense of place, and behavior (mitigation and adaptation). The book strives to engage diverse stakeholders, from multiple disciplines in addition to psychology, and at every level of decision making - individual, community, national, and international, to understand the ways in which human capabilities and tendencies can and should shape policy and action to address the urgent and very real issue of climate change.

- Examines the role of knowledge, norms, experience, and social context in climate change awareness and action

- Considers the role of identity threat, identity-based motivation, and belonging

- Presents a conceptual framework for classifying individual and household behavior

- Develops a model to explain environmentally sustainable behavior

- Draws on what we know about participation in collective action

- Describes ways to improve the effectiveness of climate change communication efforts

- Discusses the difference between acute climate change events and slowly-emerging changes on our mental health

- Addresses psychological stress and injury related to global climate change from an intersectional justice perspective

- Promotes individual and community resilience

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychology and Climate Change by Susan Clayton,Christie Manning in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Applied Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Psychology and climate change

Susan Clayton1 and Christie Manning2, 1The College of Wooster, Wooster, OH, United States, 2Macalester College, Saint Paul, MN, United States

Abstract

Climate change represents a significant threat to the wellbeing of people and societies. As the science of human behavior, psychology has much to contribute to both understanding and addressing that threat. This chapter gives an overview of the current and potential impacts of climate change on society, and outlines areas in which psychological research is relevant. Each of the remaining chapters in the volume is briefly introduced. Because climate change is ongoing and knowledge is still evolving, we highlight the urgent need for continued research in this area.

Keywords

Psychology; climate change impacts; perceptions; responses; research

Climate change requires our urgent attention. It is one of the defining issues of our time and a topic of increasing public interest and discussion; it is often described as a “wicked problem,” referring to the fact that there is no straightforward solution that will address all of the complex and multidimensional challenges that it presents. As we write, each of the past 3 years has broken previous records for global temperatures, and 2017 is likely to be the second-hottest year ever recorded, just behind 2016 (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/2017/06/supplemental/page-1). Unfortunately, this trend is likely to continue. Climate change is transforming our world.

The complexity of the geophysical processes and ecological processes involved, the likelihood of feedback loops, and the possibility of tipping points mean that our best computer models can only provide us with good estimates about the range of effects. Though the effects of climate change for a particular location or precise point in time are uncertain, it is clear that impacts around the globe will be dramatic. Temperature increases are not the only manifestation. There has already been an increase in the number of droughts as well as severe weather events worldwide (e.g., Fischer & Knutti, 2015). Artic sea ice levels are shrinking and glaciers are melting. Because of rising sea levels, coastal flooding has increased in many low-lying areas. The effects on weather and climate have been carefully described, e.g., by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014) and are continually updated with increasing certainty as the scientific evidence accumulates.

Nonhuman species have also been extensively impacted. Changes in their range and relative abundance are most visible, with some species already driven to extinction and many others facing this probability. More subtle effects in physiological and behavioral characteristics have also been documented (Pecl et al., 2017). It is not surprising that animals would change their feeding, predation, and migration habits in response to a changing climate, but the potential for cumulative, downstream impacts of these changes—potentially reconfiguring entire ecosystems—has received relatively little consideration. Species redistribution could have major implications for the many benefits that ecosystems provide to humans, with consequent impacts on the economic sphere (Pecl et al., 2017).

As climate change transforms our world, it will necessarily also transform society. Although many people think first of climate change as something that poses a threat to polar bears, the well-being of human societies is fundamentally tied to ecological well-being in a number of ways. People are already experiencing the effects of changes in the global climate, and these effects are only going to become more pronounced. To prepare for the impacts, we need to have a better understanding of the variety of ways in which climate change is likely to affect people and societies, and the kinds of responses that people and societies will show.

1.1 Direct impacts of climate change on human society

The infrastructure that supports human society was designed under climate conditions that are rapidly disappearing. Roads, bridges, power plants, city sewers, and other parts of the built environment were constructed to withstand a specific range of conditions; however, the “normal” range of conditions has shifted and will continue to shift, as the climate warms. In many communities, these infrastructural systems are already fragile due to age, or stretched beyond capacity because of population growth. With the added burden of extreme weather conditions, many places are experiencing breakdowns in basic services such as water. Infrastructure inadequacy in the face of climate change is becoming obvious as high tides, storm surges, and storm water runoff threaten underground infrastructure in coastal cities such as New York. Climate-change-fueled disruptions to industrial systems will lead to significant economic impacts and likely labor market dislocations as businesses find it too expensive to remain in climate-impacted locations.

Food production will be significantly impacted by climate change. Changing temperatures and precipitation patterns will directly affect the suitability of specific geographic locations for growing specific crops. In addition, crop production is likely to be indirectly affected by climate-change-driven shifts in the distribution of other species, particularly pollinator and pest species. Although some areas may see increased productivity, overall the effect is predicted to be negative (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2014). Meanwhile, food supplies from nonfarmed sources, including hunting and fishing, will also see dramatic changes. Food insecurity is widely predicted to be a major impact of climate change; malnutrition from the reduced availability of food due to climate change could result in over half a million deaths by 2050 (Springmann et al., 2016).

Occupations will be affected. People working in the agricultural sector are likely to experience major changes and serious difficulties, as described above; many working in tourism or recreation industries will also find their jobs changing or becoming obsolete as conditions in, e.g., coastal areas or ski resorts no longer support formerly popular activities. Human health will be affected. The American Public Health Association has emphasized the threat to health, declaring 2017 as the year of “climate change and health” (https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/climate-change). Manning and Clayton, in Chapter 9, Threats to Mental Health and Well-being Associated with Climate Change, provide a brief overview of the many ways human health will be negatively impacted by climate change manifestations such as increased temperatures, changing disease vectors, increased ground-level ozone, and natural disasters.

Climate change also presents serious threats to global security, as it is likely to exacerbate already existing tensions between nations, particularly with respect to access to fresh water. The Pentagon has classified climate change as a threat to national security (e.g., Department of Defense, 2014). Our governance system is not equipped to manage these changes. Old laws and policies will need to be adapted. New laws will need to be written. How will property rights and conservation policies, e.g., reflect the new—and continually changing—geographical realities? We are already seeing challenges related to the opening of the Arctic Ocean to shipping traffic enabled by a decline in sea ice.

1.2 The role for psychology

For most of the previous decades, the preponderance of research and writing on climate change has come from the natural sciences: climate scientists and geologists describing evidence of changes, and ecologists making predictions about their consequences. Because earlier debates were focused primarily on the adequacy of climate models and the evidence for anthropogenic causes, the field of psychology has been underrepresented in both public and academic discourse about climate change. Indeed, for many people, the topic does not seem to have psychological relevance. More recently, however, as natural scientists grow increasingly confident in their predictions, questions concerning humans and their mental and social processes have become more prominent. Why has the behavioral response to such an important threat been so muted? Why has political party become such an important predictor of climate change attitudes? And what types of social consequences can be anticipated?

Human perceptions, behavior, and well-being are clearly implicated as contributors to and/or consequences of climate change. Psychological research on phenomena such as risk perception, denial, threats to mental health, social well-being, and adaptation can and should inform public discussions of the topic. One of the most publically contested aspects of climate change is the extent to which it is a consequence of human behavior (Leiserowitz, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, Rosenthal, & Cutler, 2017); however, the science is clear: the rate and amount of change we are seeing is directly linked to human activity. Psychology, as the science of human behavior, has to be involved in discussions about how human behavior can and should be modified to slow and limit the amount of climate change, and to adjust to new climate realities.

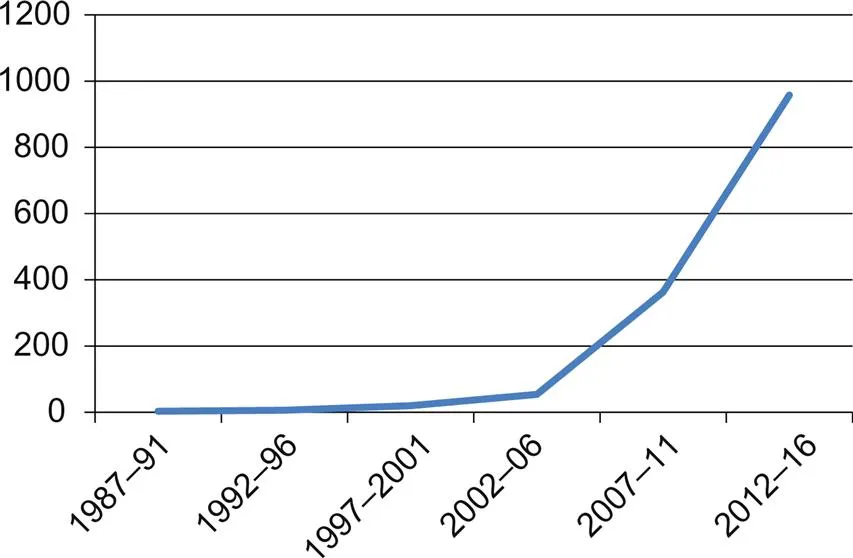

Meaningful and timely action on climate change will require engaging diverse stakeholders, both within and between nations, to develop and implement effective mitigation and adaptation policies; as such, there is an urgent need to better understand the psychological factors that drive differential engagement within pluralistic societies. In response, psychologists are directing more of their research attention to this topic. A search of PsycInfo, the most popular online research database for psychology publications, reveals a dramatically accelerating trend in works with “global warming” or “climate change” as keywords, see Fig. 1.1. The purpose of this book is to organize and summarize recent work in the field of psychology on the issue of climate change.

What does it mean to take a psychological perspective on a problem? Psychology is a broad field, grounded in some fundamental premises. This includes the understanding that individuals matter; that their perceptions, experiences, and reactions are important not only in their own right but also because they are relevant to societal outcomes. Although most of the research on the human side of climate change has emphasized institutional actors like governmental organizations, businesses, and NGOs, individual actions and perceptions matter.

It is widely accepted by scientists that human behavior has played an important role in the changing climate. The IPCC Fifth Assessment report states, “It is extremely likely that more than half of the observed increase in global average surface temperature from 1951 to 2010 was caused by the anthropogenic increase in GHG concentrations and other anthropogenic forcings together” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2014, p. 5). Industrial emissions are significant, but individual choices also matter. People make decisions about whether and how far to drive or fly, whether and how much red meat to consume, whether and how many children to have. The aggregate of individual household behavior contributes a significant proportion of carbon emissions (Dietz, Gardner, Gilligan, Stern, & Vandenbergh, 2009); transportation also represents a large amount.

Individual attitudes also influence the policies that are implemented and whether they are upheld. Public attitudes toward “green” technology are significant in determining their adoption, and thus their impact. One of the interesting—and regrettable—aspects of climate change is the extent to which contradictory assertions are made, and denied, by people holding opposing positions about the topic. Scott Pruitt, head of the US Environmental Protection Agency, e.g., has called into question the link between anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions and climate change (Chiacu & Volcovici, 2017), despite the consensus among climate scientists. US President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has referred to climate change as a “hoax” (Frisk, 2017). Such statements serve as a reminder that attitudes about climate change are formed by factors other than scientific information.

In addition to an emphasis on individuals, a psychological perspective also implies reliance on research to provide empirical evidence. Some things that may sound obvious turn out not, in fact, to be true when tested by rigorous research. For example, educating people about climate change does not necessarily change their opinions or lead them to greater concern; and paying people for sustainable behavior is generally not the best way to encourage behavior change.

Psychologists study a broad range of nested influences on individuals, from the biochemical to the intrapsychic, interpersonal, and societal, and try to recognize and assess the reciprocal interactions between these layers: the ways in which personal motives are affected by social context, for example. Some of the impacts of climate change will come directly from climate and weather; others are mediated by personal interpretations and social relationships. Psychologists utilize a wide range of methods to assess these influences. Throughout this volume the authors emphasize the source of their information and the research methodologies that were used, as well as the conclusions that were drawn.

Finally, psychology is a value-driven science in the sense that it is always mindful of the goal to promote human well-being. Many psychologists have been drawn to study phenomena related to climate change because they recognize it as a significant threat and they hope to develop interventions that can promote human well-being in the face of environmental change. To be truly effective, these interventions will need to involve researchers and practitioners from outside psychology. Our hope is that, by describing some of what psychologists know about the topic, this volume may help to facilitate such interdisciplinary projects.

1.3 Outline of the volume

Following the introductory chapter, this volume presents three sections focusing on different topics within climate change psychology. In somewhat chronological order, they focus on, first, ways in which people perceive and come to understand climate change; second, human behavioral responses to climate change; and third, impacts of climate change on human health and well-being. It is important to recognize, however, that this separation reflects a useful way of organizing the book rather than a clear distinction among topics. Behavioral responses, e.g., are fundamentally tied to perceptions, and impacts are mitigated by and dependent upon responses. Thus the themes of each section are in fact intertwined.

The first section of the book examines the ways in which the topic of climate change is represented in public understandings. Chapter 2, Percept...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1. Introduction: Psychology and climate change

- Part I: Perceptions and Communication

- Part II: Responding to Climate Change

- Part III: Wellbeing and Resilience

- Index