Chapter 1. Best Practices for Environmental Project Teams

The goal of Best Practices for Environmental Project Teams is to help Contractor project teams continuously improve competitiveness and performance on environmental restoration (ER) projects. This book is primarily directed at project team members such as Project Managers, Engineers, Geologists, Chemists, and resource staff who support one or more project teams (e.g. QC Managers, Health and Safety Managers). Best practices described in this book can be implemented by smaller Contractors who directly compete with larger Contractors. They can also help specialty subcontractors seeking to team with large or small prime Contractors. Contractor-perspective insights can help Government Environmental Restoration Service Providers obtain lower prices and better value for their ER funds, and help regulatory agencies support ER continuous improvement.

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) is the most influential driver of change, competition, and continuous improvement in our industry. They are the largest global buyer of ER services. For over three decades, they pushed the “bleeding edge” of ER cleanups within the complex and rigid legal framework. DoD has amassed the most global experience in their ongoing pursuit of best value cleanup. They have spent billions of public tax dollars over this time period. Through 30 September 2009, DoD identified 21,333 Installation Restoration Program (IRP) sites and 86% of these sites are designated as “Response Complete” [Defense Environmental Restoration Program's Annual Report to Congress, Fiscal Year 2009 (April 2010)]. DoD estimates the cost-to-complete (CTC) for IRP sites to be 6.4 billion USD and 3.8 billion USD for the emerging Military Munitions Response Program (MMRP) cleanup. This body of experience represents thousands of mistakes and lessons learned.

In 2002, DoD Component agencies (e.g. Air Force, Army, and Navy) tasked with ER began changing their acquisition strategy to foster broad competition for contracts. They continuously improved their methods of contracting to obtain lower prices for services and began shifting risk to Contractors. The increasing competition to win contracts led to lower Contractor bids, much leaner project team staffing, lower profit margins, and higher risk. One project plagued with problems and cost overruns can quickly erase the profits from several projects that have achieved project objectives and satisfied the customer. Contractor senior managers are now asking, “How can we win more contracts and avoid disaster projects that erase slim profits from other projects?”

This book summarizes ER best practices based on lessons learned over a 15-year period, from my DoD Contractor perspective as a practitioner at the programme management level. Collectively, the ER Contractor community contributed to accelerating the DoD learning curve with numerous mistakes and process improvements. We have made more mistakes in our industry than any other global industry in the world – not because we are less capable or committed to success. We work in the most complex industry in the world. Variability is the norm, which is why experienced DoD ER Remedial Project Managers (RPMs) are the most skeptical professionals in the world. Beware of the Contractor proposal that assumes everything will go as planned. Each ER project is different due to the complex mix of variables (contracts, regulatory requirements, contaminants, geology, and technologies).

U.S. taxpayer funds have been put to good use. Our ecosystem is a safer and cleaner place due to our life-long contributions and commitment to continuous improvement. Other Governments, their Government ER Service Provider organizations, regulatory agencies, project teams, and academia can capitalize on lessons learned and best practices featured in this book. This chapter provides a historical overview of the Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) and lessons learned, including editorial viewpoints from my Contractor perspective. It concludes with a summary of environmental project team challenges and best practice topics covered by Chapters 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Historical Overview of the Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) and Lessons Learned

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) began their Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) in the 1980s under the Installation Restoration Program. The DoD Environment, Safety, and Occupational Health Network and Information Exchange (DENIX) website contains a comprehensive library of historical documents. This section draws heavily upon the DERP Annual Reports to Congress from 1995 to 2009 including lessons learned from my Contractor perspective. The DoD has done an outstanding job of documenting the DERP journey.

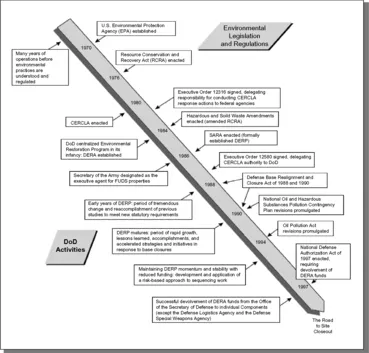

The DERP Annual Report to Congress, FY 1997, contains a graphic that describes the “Evolution of the Defense Environmental Restoration Program” (see Figure 1.1). In previous decades prior to the 1970s, the DoD, along with the United States Department of Energy (DoE), was polluting their facilities, land, and groundwater with the same lack of awareness as many corporations.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency started business on December 2, 1970a. According to the EPA website, “EPA was established to consolidate in one agency a variety of federal research, monitoring, standard-setting, and enforcement activities to ensure environmental protection. EPA's mission is to protect human health and to safeguard the natural environment – air, water, and land – upon which life depends. For more than 30 years, the EPA has been working for a cleaner, healthier environment for the American people”.

In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as Superfund. This law requires responsible parties to clean up releases of hazardous substances in the environment. The 1986 Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) refined and expanded CERCLA, and formally established DERP and funding for the programme through the Defense Environmental Restoration Account (DERA).

RCRA and CERCLA were written before any significant DoD and industry ER site cleanup experience was gained. The popular U.S. slang expression for this is “putting the cart ahead of the horse”. U.S. laws are drafted and available for public comment. However, at that time, nobody knew if the environmental legal framework would enable an efficient process and approach for implementing site cleanups. Strict Government and Contractor compliance with these laws paved the way for project work plans that would be voluminous, detailed, inflexible, and costly to change. The laws required an interactive process with various time-consuming regulatory agency document reviews. The laws also required public involvement and comment. Nobody would disagree with the necessity of engaging public involvement. But it adds more time to the process. Government attorneys review documents before they are provided to the regulatory agencies. The legal process is rigid, time-consuming, and assumes a static and predictable site cleanup process.

During the 1980s, Congress recognized that DoD no longer needed some of its installations and subsequently authorized five rounds of base realignment and closure (BRAC) in 1988, 1991, 1993, 1995, and 2005.

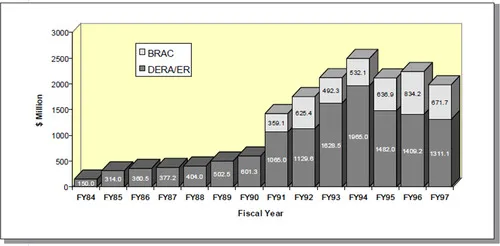

DoD activities from 1975 to 1995 focused on searching for contaminated properties, studying the problems, and writing reports. Figure 1.2 shows the level of funding from 1984 to 1997, including the amount funded to BRAC.

National Economic Stimulus

The multi-billion dollar projected cost-to-complete DoD and DoE cleanup that emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s created a new “environmental cleanup industry” that attracted several large corporations. Corporations and small businesses made substantial investments into “innovative site cleanup technologies”. At that time, the industry had an aura of “gold-rush” prospecting because Government and corporations were looking for “silver-bullet” technology remedies. Many optimists perceived that if the United States can put a man on the moon, then certainly we could meet the challenge of developing innovative technologies to clean up contamination. A variety of speciality subcontractors and analytical laboratories targeted the growing ER industry. Rapid economic growth corresponded with cyclical downturns and downsizing in domestic industries, such as petroleum exploration, nuclear power plant construction, and aerospace. National symposia and conferences attracted scientists, engineers, and regulatory professionals from other countries who were committed to cleaning up contaminated sites.

Universities were caught off guard by the rapid emergence of the environmental cleanup industry. Good professional salaries, interesting projects, extensive research and development, and working outdoors in scenic locations offered very appealing career opportunities for scientists and engineers. The resultant high corporate demand lured many scientists and engineers to join companies that were positioning their capabilities and resources to help clean up the environment. Professionals who transferred from other industries leveraged their experience and college educations in Geology, Chemistry, Engineering, and Biology. To this day, very few senior professionals in our industry began their college education with the goal of doing this type of work, and most take pride in contributing to a cleaner earth.

DoD Pressure to Decrease Studies and Increase Site Cleanups

In the mid-1990's, the U.S. Congress, public, and communities threatened or impacted by contaminated DoD properties thought too much funding was being spent on “studies” and not enough on “site cleanups”. The DERP was under pressure to transition the programme towards accelerated site cleanup. The Defense Environmental Restoration Program Annual Report to Congress, FY 1995, contains the following quote from President Bill Clinton:

“Environmental experts from EPA, DoD, and the state will work together, and a professional cleanup team will be stationed at every site.”

–President Clinton, July 1993

The 1995, Defense Environmental Restoration Program Annual Report to Congress, FY 1995, describes a series of monumental changes to the DERP, such as “Accelerating Cleanup”, “Fast-track Cleanup Moves Ahead”, and “Strengthening the Program”. DoD published highlights of its continuous self-evaluation efforts in a report entitled Fast-Track Cleanup, Successes and Challenges, 1993–1995.

Measuring Performance

DoD developed “Measures of Merit” to measure progress towards goals. Newly developed measures provided crucial feedback needed to develop and adjust programme requirements and budget projections, as well as determine whether established goals reflected fiscal reality.

Three separate categories of Measures of Merit were developed to assess site remediation progress from one discrete time period to the next, generally at the end of each fiscal year:

Relative Risk Reduction. This measurement applied only to DERA and BRAC sites that were ranked using the relative risk site evaluation framework. DoD classified sites as having a high, medium, or low relative risk; response complete; or no further action required.

Progress at sites. Gauging the progress of restoration efforts was still a critical measure that required status reports on particular phases of investigation, design, cleanup,...