- 275 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Urban Climate

About this book

The Urban Climate aims to summarize analytical studies directed toward physical understanding of the rural-urban differences in the atmospheric boundary layer. Attempts to quantify conditions have met with some success. There is certainly a clear understanding of the physical relations that create the climatic differences of urbanized areas. Although some of the earlier classical studies are cited here, the emphasis is on the work done during the last decade and a half. This volume comprises 11 chapters, beginning with an introductory chapter discussing the literature surrounding the topic, its historical development, and the problem of local climate modification. The second chapter presents an assessment of the urban atmosphere on a synoptic and local scale, and examines the observational procedures involved. The following chapters then go on to discuss urban air composition; urban energy fluxes; the urban heat island; the urban wind field; models of urban temperature and wind fields; moisture, clouds, and hydrometeors; urban hydrology; special aspects of urban climate; and finally, urban planning. This book will be of interest to practitioners in the fields of meteorology, urban planning, and urban climatology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 The Literature

The field of urban climatology has grown rapidly in recent years. This is reflected in the phenomenal increase in literature. When Father Kratzer wrote his first book on the subject, an outgrowth of his dissertation, he cited 225 papers (Kratzer, 1937). The second edition (Kratzer, 1956) listed 533 publications. A selective, annotated bibliography by C. E. P. Brooks (1952) found 249 items worthy of abstracting. That was about the time when the modern era of investigation started. Thus we find in Chandler’s (1970) comprehensive bibliography, prepared for the World Meteorological Organization, some 1800 titles. This was followed by a review of progress between 1968 and 1973 by Oke (1974) citing 377 papers that had appeared since Chandler’s work. The same author again reviewed the increment in pertinent literature between 1973 and 1976 (Oke, 1979) and found 434 references worthy of citation. A recent bibliography restricted to Australian contributions gives some 554 titles, some of only peripheral relation to the urban climate theme.

This enormous increase in literature reflects the growing concern about man’s influence on his environment. This concern kindled all kinds of inquiries in many parts of the world. The efforts to gain insight into the man-made climatic alteration in cities ranged from the profound to the trivial. The momentum gathered in recent years will carry these inquiries forward for a while yet. Such work can elucidate further details here and there or add other towns to the list for which data are obtained, generally only confirming older results. The main remaining tasks are to translate these results for use by urban planners and to clarify that elusive mechanism of urban-induced precipitation and its areal extent.

A major effort was made to come to grips with the latter problem in project METROMEX, which was a comprehensive study of the atmospheric effects of a major metropolitan area. Extensive reports have been rendered (Changnon et al.,1977; Ackerman et al.,1978), and a whole issue of the Journal of Applied Meteorology has been devoted to general publication of results of this project (Changnon, 1978). Any student interested in the topic of urban climatology must refer to these original studies. It was this project that brought this field of scientific inquiry to its present plateau. Because of the vastness of the literature (well in excess of 3000 titles), its recent repetitive character, and the excellent bibliographical resources cited earlier, only direct sources of material given in this book will be cited henceforth.

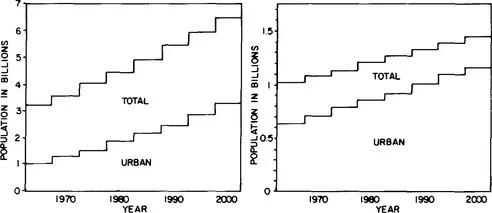

We may be justified in asking: Why has the topic reached such dimensions? The reason is simple. Cities and metropolitan areas have grown into vast conurbations, where a variety of human influences impinge on the local atmosphere—and the end is not in sight. United Nations projections indicate that by the end of the twentieth century over 6 billion people will live on earth, about 50 percent of them crowded into urban areas. In the so-called developed world the expectation is for about 1.4 billion inhabitants with about 80 percent living in cities (Fig. 1.1). In a few short years some metropolitan areas will reach the 20-million population figure. Clearly, in addition to the vast changes that have already taken place, further transformations of land must take place to accommodate these people. More fuel must be used, more waste heat dissipated, more pollutants dispersed to furnish housing, employment, and transportation to these masses. All of this impinges on the atmosphere. The ecological impact is enormous. This has been a topic for debate for over a decade. A number of these discussions have found their way into print and the reader should take time to look at the larger context. Urban climate is just one small facet of a much larger problem facing mankind (see, e.g., Eldridge, 1967; Dansereau, 1970).

Fig. 1.1 United Nations projections of population in the world (left) and in developed areas (right) to the year 2000, with the percentage living in urban areas.

1.2 Historical Developments

Ever since cities developed in antiquity, people noticed that urban air was different from rural air. They sensed a persistent evil of cities with that highly sensitive chemical monitor, the nose. The reaction is to air pollution. Although the sources have changed through the ages, polluted air seems to be the hallmark of the urban atmosphere.

An allusion to Roman smoke pollution already appears in the odes of Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace, 65–68 B.C.) about 24 B.C. (Neumann, 1979). More specifically we read in the writings of Lucius Annaeus Seneca (ca. 3 B.C.–A.D. 65): “As soon as I had left the heavy air of Rome with its stench from smoky chimneys which, when stoked, will belch their enclosed pestilential vapor and soot, I felt a change in mood.”

In the outgoing Middle Ages London became the prototype of urban pollution. It prompted prohibition of coal burning in 1273. This was to little avail. In 1306 King Edward I (1239–1307) issued a proclamation banning the burning of sea coal in furnaces. Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) banned the burning of coal in the city during sessions of Parliament. The great naturalist, John Evelyn (1620–1706), a Fellow of the Royal Society, wrote a pamphlet in 1661 decrying the use of coal for manufacturing. In it he said: “For in all other places the Aer is most Serene and Pure, it is here Ecclipsed with such Cloud of Sulphure as the Sun itself, which gives day to all the World besides, is hardly able to penetrate and impart it here; and the weary Traveller at many Miles distance, sooner smells, than sees the City to which he repairs.” The pollution problem persisted for nearly another 300 years until an air pollution episode in 1952 caused 4000 excess deaths and led to legislation that converted this and other English cities into “smokeless” zones.

London appeared again in the annals of urban climatology when in 1818 Luke Howard (1772–1864, Fig. 1.2) published the first edition of a book dealing with the climate of the city. A second volume appeared in 1820 and a third, enlarged edition was published in 1833. Howard, a chemist, was a pioneering amateur meteorologist. His cloud classification of 1803 is still the basis for cloud identification. In his book, also incidentally the first monographic treatment of the climate of a city, Howard clearly recognized a major alteration of a meteorological element. For this he created the term “city fog.” He vividly described the phenomenon for several cases. About January 10, 1812 he wrote:

Fig. 1.2 Portrait of Luke Howard (1772–1864), FRS, discoverer of London’s heat island.

London was this day involved, for several hours, in palpable darkness. The shops, offices &c were necessarily lighted up; but the streets not being lighted as at night, it required no small care in the passenger to find his way and avoid accidents. The sky, where any light pervaded it, showed the aspect of bronze. Such is, occasionally, the effect of the accumulation of smoke between two opposite gentle currents, or by means of a misty calm. I am informed that the fuliginous cloud was visible, in this instance, for a distance of forty miles. Were it not for the extreme mobility of the atmosphere, this volcano of a thousand mouths would, in winter be scarcely habitable.

The colorful description of the urban scene as a volcano has been rep...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Inside Front Cover

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Assessment of the Urban Atmosphere

- Chapter 3: Urban Air Composition

- Chapter 4: Urban Energy Fluxes

- Chapter 5: The Urban Heat Island

- Chapter 6: The Urban Wind Field

- Chapter 7: Models of Urban Temperature and Wind Fields

- Chapter 8: Moisture, Clouds, and Hydrometeors

- Chapter 9: Urban Hydrology

- Chapter 10: Special Aspects of Urban Climate

- Chapter 11: Urban Planning

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- International Geophysics Series

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Urban Climate by Helmut E. Landsberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.