- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Research in Organizational Behavior

About this book

Volume 22 of Research in Organizational Behavior continues the tradition of innovation and theoretical development with eight diverse papers. Most of these papers present theory and propositions that make linkages between different levels of analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Research in Organizational Behavior by B.M. Staw,R.I. Sutton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Network Structure Of Social Capital

Ronald S. Burt

ABSTRACT

This is a review of argument and evidence on the connection between social networks and social capital. My summary points are three: (1) Research and theory will better cumulate across studies if we focus on the network mechanisms responsible for social capital effects rather than trying to integrate across metaphors of social capital loosely tied to distant empirical indicators. (2) There is an impressive diversity of empirical evidence showing that social capital is more a function of brokerage across structural holes than closure within a network, but there are contingency factors. (3) The two leading network mechanisms can be brought together in a productive way within a more general model of social capital. Structural holes are the source of value added, but network closure can be essential to realizing the value buried in the holes.

INTRODUCTION

Social capital is fast becoming a core concept in business, political science, and sociology. An increasing number of research articles and chapters on social capital are appearing (look at the recent publication dates for the references to this chapter), literature reviews have begun to appear (e.g. Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Portes, 1998; Sandefur & Laumann, 1998; Woolcock, 1998; Foley & Edwards, 1999; Lin, 1999; Adler & Kwon, 2000), books are dedicated to it (e.g. Leenders & Gabbay, 1999; Baker, 2000; Lesser, 2000; Lin, Cook, & Burt, 2001; Lin, forthcoming), and the term in its many uses can be found scattered across the internet (as a business competence, a goal for non-profit organizations, a legal category, and the inevitable subject of university conferences). Portions of the work are little more than loosely-formed opinion about social capital as a metaphor, as is to be expected when such a concept is in the bandwagon stage of diffusion. But what struck me in preparing this review is the variety of research questions on which useful results are being obtained with the concept, and the degree to which more compelling results could be obtained and integrated across studies if attention were focused beneath the social capital metaphor on the specific network mechanisms responsible for social capital. For, as it is developing, social capital is at its core two things: a potent technology and a critical issue. The technology is network analysis. The issue is performance. Social capital promises to yield new insights, and more rigorous and stable models, describing why certain people and organizations perform better than others. In the process, new light is shed on related concerns such as coordination, creativity, discrimination, entrepreneurship, leadership, learning, teamwork, and the like – all topics that will come up in the following pages. I cover diverse sources of evidence, but focus on senior managers and organizations because that is where I have found the highest quality data on the networks that provide social capital.1 The goal is to determine the network structures that are social capital.

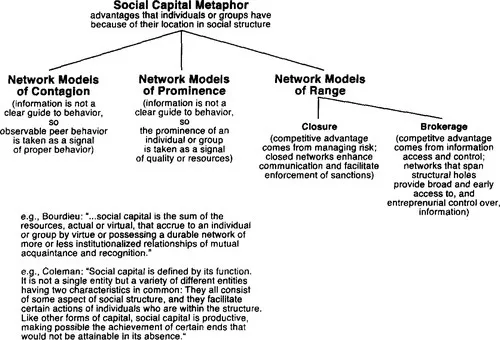

SOCIAL CAPITAL METAPHOR

Figure 1 is an overview of social capital in metaphor and network structure. The figure is a road map through the next few pages, and a reminder that beneath the general agreement about social capital as a metaphor lie a variety of network mechanisms that make contradictory predictions about social capital.

Fig. 1 Social Capital, in Metaphor and Network Structure.

Cast in diverse styles of argument (e.g. Coleman, 1990; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992; Burt 1992; Putnam, 1993), social capital is a metaphor about advantage. Society can be viewed as a market in which people exchange all variety of goods and ideas in pursuit of their interests. Certain people, or certain groups of people, do better in the sense of receiving higher returns to their efforts. Some enjoy higher incomes. Some more quickly become prominent. Some lead more important projects. The interests of some are better served than the interests of others. The human capital explanation of the inequality is that the people who do better are more able individuals; they are more intelligent, more attractive, more articulate, more skilled.

Social capital is the contextual complement to human capital. The social capital metaphor is that the people who do better are somehow better connected. Certain people or certain groups are connected to certain others, trusting certain others, obligated to support certain others, dependent on exchange with certain others. Holding a certain position in the structure of these exchanges can be an asset in its own right. That asset is social capital, in essence, a concept of location effects in differentiated markets. For example, Bourdieu is often quoted as in Fig. 1 in defining social capital as the resources that result from social structure (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 119, expanded from Bourdieu, 1980). Coleman, another often-cited source as quoted in Fig. 1, defines social capital as a function of social structure producing advantage (Coleman, 1990, p. 302; from Coleman 1988, S98). Putnam (1993, p. 167) grounds his influential work in Coleman’s argument, preserving the focus on action facilitated by social structure: “Social capital here refers to features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated action.” I echo the above with a social capital metaphor to begin my argument about the competitive advantage of structural holes (Burt, 1992, pp. 8, 45).

So there is a point of general agreement from which to begin a discussion of social capital. The cited perspectives on social capital are diverse in origin and style of accompanying evidence, but they agree on a social capital metaphor in which social structure is a kind of capital that can create for certain individuals or groups a competitive advantage in pursuing their ends. Better connected people enjoy higher returns.

NETWORK MECHANISMS

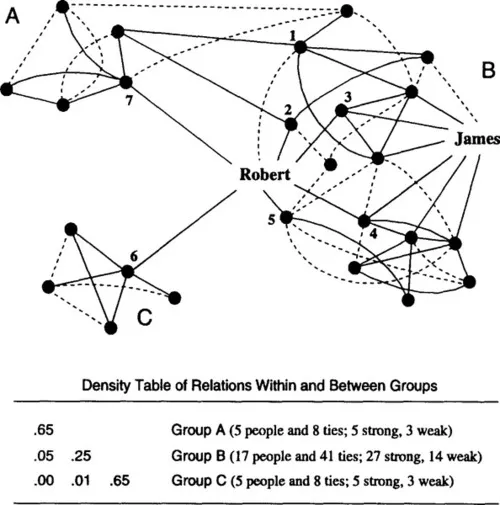

Disagreements begin when the metaphor is made concrete in terms of network mechanisms that define what it means to be ‘better connected’. Connections are grounded in the history of a market. Certain people have met frequently. Certain people have sought out specific others. Certain people have completed exchanges with one another. There is at any moment a network, as illustrated in Fig. 2, in which individuals are variably connected to one another as a function of prior contact, exchange, and attendant emotions. Figure 2 is a generic sociogram and density table description of a network. People are dots. Relations are lines. Solid (dashed) lines connect pairs of people who have a strong (weak) relationship.

Fig. 2 Social Organization.

In theory, the network residue from yesterday should be irrelevant to market behavior tomorrow. I buy from the seller with the most attractive offer. That seller may or may not be the seller I often see at the market, or the seller from whom I bought yesterday. So viewed, the network in Fig. 2 would recur tomorrow only if buyers and sellers come together as they have in the past. The recurrence of the network would have nothing to do with the prior network as a casual factor. Continuity would be a by-product of buyers and sellers seeking one another out as a function of supply and demand.

Networks Affect and Replace Information

Selecting the best exchange, however, requires that I have information on available goods, sellers, buyers, and prices. This is the point at which network mechanisms enter the analysis. The structure of prior relations among people and organizations in a market can affect, or replace, information.

Replacement happens when market information is so ambiguous that people use network structure as the best available information. Such assumption underlies the network contagion and prominence mechanisms to the left in Fig. 1. For example, transactions could be so complex that available information cannot be used to make a clear choice between sellers, or available information could be ambiguous such that no amount of it can be used to pick the best exchange. White (1981) argues that information is so ambiguous for producers that competition is more accurately modeled as imitation. A market is modeled as a network clique (in other words, a small, cohesive group distinct from an external environment). Price within the clique is determined by producers taking positions relative to other producers on the market schedule. Information quality is also the problem addressed in Podolny’s concept of status as market signal (Podolny, 1993; Podolny, Stuart & Hannan, 1997; Benjamin & Podolny, 1999). In his initial paper, Podolny (1993) described how investors not able to get an accurate read on the quality of an investment opportunity look to an investment bank’s standing in the social network of other investment banks as a signal of bank quality, with the result that banks higher in status are able to borrow funds at lower cost. More generally, presumptions about the inherent ambiguity of market information underlie social contagion explanations of firms adopting policies in imitation of other firms (e.g. Greve, 1995; Davis & Greve, 1997; see Strang & Soule, 1998, for review; Burt, 1987, on the cohesion and equivalence mechanisms that drive contagion). Zuckerman’s (1999) market model is an important new development in that the model goes beyond producer conformity to describe penalties that producers pay for deviating from accepted product categories, and the audience (mediators) that enforce the penalties.

The network contagion and prominence mechanisms describe social capital. Contagion can be an advantage in that social structure ensures the transmission of beliefs and practices more readily between certain people and organizations (a theme in Bourdieu’s discussion of cultural capital), and of course, network prominence has long been studied as an advantage for people (e.g. Brass, 1992) and organizations (e.g. Podolny, 1993).

Although contagion and prominence mechanisms can be discussed as social capital, they are more often discussed as other concepts – for example, imitation in institutional theory, or reputation and status in economics and sociology – so I put them aside for this turn-of-the-century review. Future reviewers will not be so lucky. The contagion and prominence mechanisms are not ideas around which current social capital research has accumulated, but they certainly could be, and so are likely to be in future if the social capital metaphor continues to be so popular.

The other two mechanisms in Fig. 1, closure and brokerage, have been the fou...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright page

- List of contributors

- Preface

- How Emotions Work: The Social Functions of Emotional Expression in Negotiations

- Contagious Justice: Exploring The Social Construction of Justice in Organizations

- Theories of Gender in Organizations: A New Approach to Organizational Analysis and Change1

- Coordination Neglect: How Lay Theories of Organizing Complicate Coordination in Organizations

- Corporations, Classes, and Social Movements After Managerialism

- Power Plays: How Social Movements and Collective Action Create New Organizational Forms

- The Kibbutz for Organizational Behavior

- The Network Structure Of Social Capital