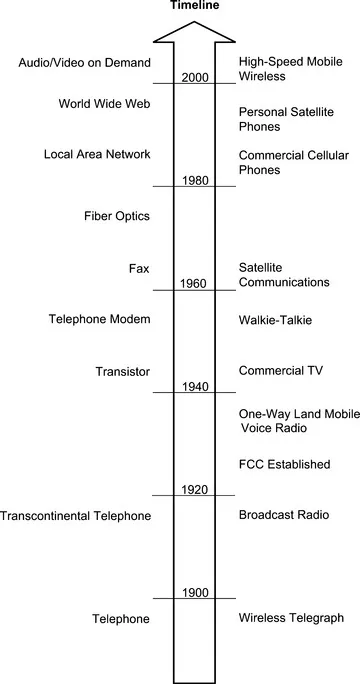

A short history of wireless communication

Figure 1.0-1 shows a time line of the development of wireless communications. We are well into the second century of radio communications. The pioneering work of Faraday, Maxwell, Hertz, and others in the 1800s led to Marconi’s wireless telegraph at the turn of the century. The precursors to mobile radio as we know it have been available since the first transportable voice radios of the 1920s. Radio technology matured in the subsequent decades, with broadcast radio and television, and the portable manpack walkie-talkies of World War II. In the 1940s, cellular technology was conceived, with the ability to divide radio frequency service areas into “cells” to reduce interference and increase capacity. This is the basis for today’s wide area voice and wireless local area networking technologies. Within a few years of the first satellite launch in 1957, satellites were being sent into space to act as communication relays.

Figure 1.0-1 The graph indicates general telecommunications advances on the left and wireless-specific advances on the right.

In 1969, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allotted portions of the radio frequency spectrum for mobile telephones. In the 1970s the Post Office Code Standardization Advisory (POCSAG) numeric paging code was standardized, and AT&T rolled out the first mobile telephone services operating on a cellular system. In 1987, the FCC allowed the use of new technologies in the 800 MHz cellular spectrum, with the first digital cellular transmissions (code division multiple access [CDMA], time division multiple access [TDMA], and global system for mobile communication [GSM]) tested in the United States shortly thereafter. With the adoption of digital technologies, new features such as voice mail, fax, and short messages have been enabled.

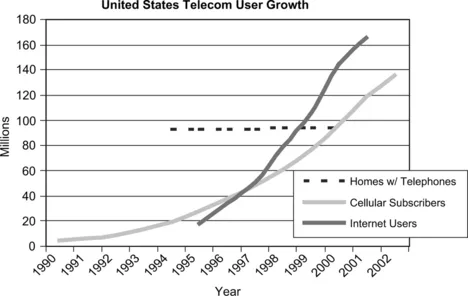

The boom in wireless usage in the 1990s (paralleling the Internet boom) has led to near ubiquitous wireless voice service throughout the United States and in much of the world. Personal wireless data services, exemplified by such technologies as short message service (SMS), wireless application protocol (WAP), ReFlex, Bluetooth, i-Mode, and 802.11, offer a range of mobile data services that are not far behind. For every wireline technology, from serial cable to fiber optics, there is an analogous wireless technology available when it is not feasible or convenient to use a cable connection. Figure 1.0-2 depicts how rapidly newer technologies grew in the 1990s while the number of wireline telephone installations in homes remained relatively static.

Figure 1.0-2 United States Telecom User Growth. With voice line penetration in saturation, wireless and Internet users continue to grow. Wireless data usage will follow. (Internet users include the United States and Canada.)

Where we are

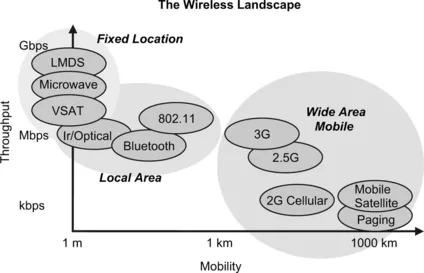

Today’s wireless technologies offer an immense range of capabilities to the user. System throughputs continue to expand, offering the ability to support an increasing number of applications. Wireless communication system availability is also increasing, due to investment in fixed infrastructure, as well as reduced device cost and size.

Figure 1.0-3 categorizes select wireless technologies, graphed by system throughput and user mobility. Several groupings are identified for convenience. On the left are Fixed Location systems, such as point-to-point microwave and stationary satellite systems, which generally operate at high rates (over one Mbps) on line-of-sight channels. Near the fixed systems, providing limited mobility over shorter transmission paths but still supporting Mbps data rates, are Local Area systems, such as wireless local area networks (802.11) and personal area networks (Bluetooth). Finally, Wide Area Mobile systems, such as paging and cellular, provide extended mobility but with relatively limited throughput. These categories are explored in the following section.

Figure 1.0-3 Current technologies in the wireless landscape provide a range of choices, from high-bandwidth fixed systems to wide area systems supporting low to moderate data rates.

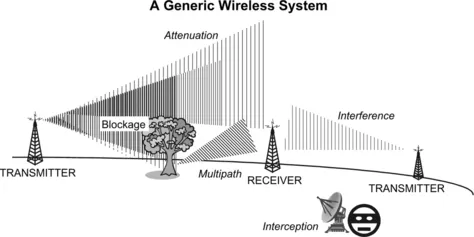

Before entering a discussion of specific wireless technologies, it is useful to review the relevant characteristics of a generic radio system. Figure 1.0-4 illustrates a wireless system, showing a signal sent from the transmitter on the left to the receiver in the center. Other aspects of the environment are shown to highlight the challenges inherent in wireless communications. These challenges are the focus of much research aimed at improving RF communications.

Figure 1.0-4 A generic wireless system. Inherent weaknesses of the wireless medium are offset by its flexibility and support for mobility.

First, even in the best of situations, we have free space attenuation, where the signal loses strength at a rate proportional to the square of the distance traveled. This limits the signal propagation distance. The electromagnetic radio waves are further attenuated due to blockage by objects (including atmospheric particles) in their propagation paths. Both types of attenuation limit the ability of the receiver to capture and interpret the transmitted signal.

Additionally, radio signals are subject to reflection, which leads to multipath fading, another form of signal loss. A reflected signal, since it travels a longer distance between transmitter and receiver, arrives at the receiver with a time delay relative to a signal following a direct (or shorter reflected) path. Two similar signals, offset in time, may cancel each other out.

Another difficulty facing the receiver operating in the unprotected wireless environment is the possibility of other similar signals sharing the same medium and arriving at the receiver simultaneously with the desired signal, thus causing interference. Finally, the unprotected medium also allows the possibility of eavesdropping, or interception, where a third party captures the transmitted signal without permission, potentially compromising the privacy of the system’s users.

Each of the challenges illustrated in Figure 1.0-4 identifies an area where wireless communications is at a disadvantage to a comparable wireline communication system. Why then are wireless communications so prevalent? Each wireless deployment may have its own design rationale, but two fundamental reasons cover most cases. First, wireless systems provide flexibility in deployment. Whether connecting a laptop PC in a conference room or a pipeline monitor in the Arctic, the setup of a radio connection may be orders of magnitude faster than a wireline connection, due to the fact that no physical connecting media is required. Second, wireless systems can provide the option of mobility. Communicating on the move is very useful, if not critical, to many applications, and this is just not well supported through a wired medium.

Note that some of these “weaknesses” can cleverly be turned to the user’s advantage. For example, attenuation and blocking may be le...