Geological Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide

Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Reaction Path Modeling

- 470 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Geological Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide

Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Reaction Path Modeling

About this book

The contents of this monograph are two-scope. First, it intends to provide a synthetic but complete account of the thermodynamic and kinetic foundations on which the reaction path modeling of geological CO2 sequestration is based. In particular, a great effort is devoted to review the thermodynamic properties of CO2 and of the CO2-H2O system and the interactions in the aqueous solution, the thermodynamic stability of solid product phases (by means of several stability plots and activity plots), the volumes of carbonation reactions, and especially the kinetics of dissolution/precipitation reactions of silicates, oxides, hydroxides, and carbonates. Second, it intends to show the reader how reaction path modeling of geological CO2 sequestration is carried out. To this purpose the well-known high-quality EQ3/6 software package is used. Setting up of computer simulations and obtained results are described in detail and used EQ3/6 input files are given to guide the reader step-by-step from the beginning to the end of these exercises. Finally, some examples of reaction-path- and reaction-transport-modeling taken from the available literature are presented. The results of these simulations are of fundamental importance to evaluate the amounts of potentially sequestered CO2, and their evolution with time, as well as the time changes of all the other relevant geochemical parameters (e.g., amounts of solid reactants and products, composition of the aqueous phase, pH, redox potential, effects on aquifer porosity). In other words, in this way we are able to predict what occurs when CO2 is injected into a deep aquifer.* Provides applications for investigating and predicting geological carbon dioxide sequestration* Reviews the geochemical literature in the field* Discusses the importance of geochemists in the multidisciplinary study of geological carbon dioxide sequestration

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

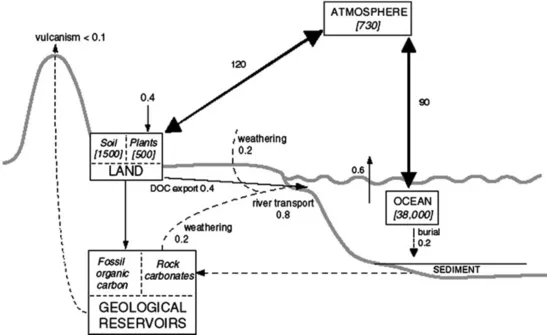

Why We Should Care: The Impact of Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide on the Carbon Cycle

1.1 Carbon dioxide: from its discovery to the understanding of its role

1.2 The short-term carbon cycle

1.2.1 The terrestrial biosphere

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Developments in Geochemistry

- Front Matter

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Why We Should Care: The Impact of Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide on the Carbon Cycle

- Chapter 2: The Thermodynamic Background

- Chapter 3: Carbon Dioxide and CO2–H2O Mixtures

- Chapter 4: The Aqueous Electrolyte Solution

- Chapter 5: The Product Solid Phases

- Chapter 6: The Kinetics of Mineral Carbonation

- Chapter 7: Reaction Path Modelling of Geological CO2 Sequestration

- References

- Subject Index