![]()

Chapter 1

Milestones in the Development of Gas Chromatography

Walter G. Jennings and Colin F. Poole

Outline

1.1. Introduction

1.2. The Invention of Gas Chromatography

1.3. Early Instrumentation

1.3.1. Early Commercial Instruments

1.4. Early Column Developments

1.4.1. Do-it-Yourself Glass Capillary Columns

1.4.2. The Positive Results of Patent Enforcement

1.4.3. Mileposts in Coating WCOT Capillary Columns

1.4.4. Commercial Column Manufacturers

1.4.5. Bonded, Crosslinked, and/or Immobilized Stationary Phases

1.4.6. Further Improvements in Stationary Phases

1.5. Interfacing Glass Capillary Columns to Injectors and Detectors

1.6. The Hindelang Conferences and the Fused-Silica Column

1.7. Increasing Sophistication of Instrumentation

1.7.1. Column Heating

1.7.2. Sample Introduction

1.7.3. Detectors

1.7.4. Data Handling

1.7.5. Comprehensive Gas Chromatography

1.8. Decline in the Expertise of the Average Gas Chromatographer

1.1 Introduction

This article was started by the senior author Walter Jennings who was unable to complete it due to poor health. Sections 1.2–1.6 are a personal account of the early days of gas chromatography seen through the eyes of one of the major pioneers and innovators in this field. With only minor editorial changes made by the junior author, these are presented as Walter intended. As the junior author I am responsible for Sections 1.7 and 1.8. These sections extend Walter’s comments on the early days of gas chromatography to the present day.

1.2 The Invention of Gas Chromatography

In 1952 A.J.P. Martin and R.L.M. Synge were both awarded Nobel Prizes for their work in the field of liquid/solid chromatography. Martin, in his award address, suggested it might be possible to use a vapor as the mobile phase. Some years later, James and Martin used ethyl acetate vapor to desorb a mixture of fatty acids that had been affixed to an adsorbent, and placed in a tube. The vapor stream eluting from that tube was directed to an automated titration apparatus, resulting in a graph showing a series of “steps” that reflected the sequential additions of base as each eluted acid was neutralized by automated titration [1]. Many practitioners have for far too long considered this as the starting point of gas chromatography.

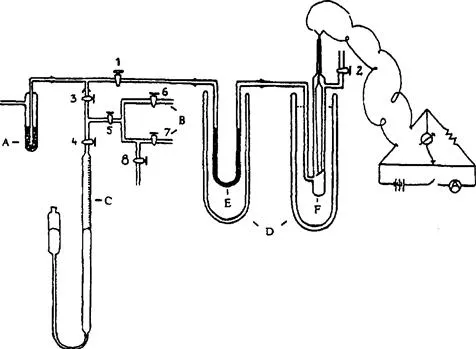

In 2008 Leslie Ettre published an article in which he stated, “… the activities of Professor Erika Cremer and her students at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, in the years following the Second World War, represented the true start of their continuous involvement in gas chromatography” [2]. After exploring Ettre’s arguments and conducting some research myself, I fully agree with his conclusions. I now believe that the theoretical basis for gas chromatography was first conceived by Erika Cremer, an Austrian scientist at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, in the late 1940s during the period of the Second World War. As Ettre points out, this was a period when women, especially in Germanic countries, were expected to confine their activities to “children, church, and kitchen”. In spite of her “superb Ph.D. thesis work” she had great difficulty in finding a position. Her opportunity came in 1940 when the war started, and university teachers were drafted. She obtained an academic position at the University of Innsbruck, Austria (then a part of Germany) in the Institute of Physical Chemistry. It was here that she and her students (with major credit to Fritz Prior) constructed the first prototype of a gas chromatograph (Figure 1.1) and, after a long delay that was probably attributable to the war, published the results of their research in 1951 [3,4]. At this time she was promoted to Professor and, some twenty years later, to director of the University’s Institute of Physical Chemistry. Professor Dr. Cremer, by all accounts a brilliant woman scientist, died in 1996.

FIGURE 1.1 The gas chromatographic system used in Prior’ work, in 1945–1947. A = adsorbent for purification of the carrier gas (hydrogen); B = sample inlet system; C = buret containing mercury with niveau glass for sample introduction; D = Dewar flask; E = separation column (containing silica gel on activated carbon); and F = thermal conductivity detector.

Source: From ref. [4] copyright Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn.

1.3 Early Instrumentation

By 1953, several petroleum companies, primarily in Great Britain and the Netherlands, were exploring this new analytical technique, and in 1954, a few flavor chemists (including this author) were building crude chromatographs, many of them based on an article by N. H. Ray [5]. Ray inserted thermal conductivity cells into a Wheatstone bridge, whose outlet connected to a strip chart recorder, thus generating a Gaussian peak for each eluting solute; this was (to my knowledge) the first gas chromatogram as we know them today. The schematics and chromatograms published by Ray encouraged a number of readers (including the author) to build similar chromatographs. Almost every part of these crude instruments had to be self-designed and self-made, but this introduced the days of the packed column; supports, such as granules of diatomaceous earth, were coated with a variety of high boiling fluids (e.g. diethylene glycol succinate, DEGS) and, in our earliest efforts, packed into copper columns, typically 3–6 m long with internal diameters of about 6 mm, and (usually) coiled. It was soon recognized that copper columns were quite active and most workers switched, first to stainless steel, and then to coiled glass tubing of similar dimensions. The reminiscences of many of the early pioneers in gas chromatographic instrumentation are summarized in [6].

1.3.1 Early Commercial Instruments

The first companies to manufacture gas chromatographs (GCs) in Europe were Griffin and George (London) and Metropolitan Vickers Electric (Manchester), but the U.S. instrument companies had a greater impact on the development of this new area [7]. Perkin Elmer was one of the first companies to market a gas chromatograph; in May of 1954, they introduced their Model 154 Vapor Fractometer. The temperature of the column oven was adjustable from room temperature to 150 °C, and it offered a “flash vaporizer” with a rubber septum permitting syringe injection into the carrier gas stream. The detector was a thermal conductivity cell. The instrument was a great success and sold widely [8]. In early 1956, Perkin Elmer followed up with their Model 154-B, with a temperature range from room temperature to 225 °C and could be fitted with an optional rotary valve offering a variety of sample loops for the injection of gas samples.

1.4 Early Column Developments

All of the early instruments utilized packed columns, some coiled, some U-shaped. Packed columns all have one thing in common: they possess a high resistance to gas flow, and this limits the practical length of the column, usually to a few meters. In much later days, some packed columns approached an efficiency equivalent to our current 0.32 mm internal diameter capillary columns (ca. 3000 plates per meter), but because of their length limitations, they could achieve perhaps 35,000 theoretical plates while a 30 m open-tubular 0.25 mm internal diameter column should be capable of three times that efficiency, merely because it is three times longer.

It was at the 1958 Second International Symposium on Gas Chromatography in Amsterdam that Marcel Golay, who was then a consultant to Perkin Elmer, introduced the theory of open-tubular capillary columns and demonstrated their superiority to packed columns [9]. (There is no connection between the old Perkin Elmer referred to here and the Perkin Elmer of today, they are entirely different companies.) These columns demanded much smaller sample injections, necessitating more sensitive detectors than the thermal conductivity detectors that were in common use at the time. Fortunately, James E. Lovelock had invented an electron-capture detector in 1957 [10], and in 1958 the flame ionization detector appeared; some credit this to Harley, Nel, and Pretorious [11], and others to McWilliams and Dewer [12,13]; these increased detector sensitivities by ca. 103–106. The invention and development of the flame ionization detector is discussed in more detail in [14]. Early capillary columns were of plastic and copper tubing; the former had serious temperature limitations and the latter was active; this led to stainless steel tubing. Perkin Elmer had filed for and been granted patents on the open-tubular concept, essentially worldwide. I purchased two Perkin Elmer wall-coated open-tubular (WCOT) columns at different times, only to find that the columns available from them produced abominable results. Perkin Elmer apparently recognized this fact, because they essentially abandoned their research efforts on WCOT columns, outsourced their production, and re-directed their efforts to columns whose interiors were first coated with a support material (e.g. diatomaceous earth) and then with the stationary phase. These were dubbed “support coated open-tubular (SCOT) columns”. Perkin Elmer continued to rigorously enforce the patent on WCOT (and SCOT) columns, but under considerable pressure (especially from the applicant) they were forced to issue one license, to Hansjurg Jaeggi, a former assistant of Kurt Grob in Switzerland. Under Swiss law, if a patent bars a Swiss from conducting his or her business, a license must be issued. Jaeggi had been and still was making excellent glass WCOT columns. The high quality of his columns led Perkin Elmer to later propose that they collaborate, but, probably because of the acrimonious battle he had gone through to obtain his license, he wanted nothing more to do with Perkin Elmer, and refused their offer. His obituary, written by Konrad Grob, makes interesting reading [15].

1.4.1 Do-it-Yourself Glass Capillary Columns

In 1965, Desty et al. invented an elegantly simple machine for drawing long lengths of coiled glass capillaries [16]. Besides the fact that his was much less expensive tubing, it also had a smoother interior and it was transparent. For the first time, it was possible to scrutinize the layer of stationary phase as it existed on the column wall; soon it was obvious that when a new unused column exhibiting a thin uniform film of stationary phase was exposed to higher temperatures, the stationary phase collected into beads that were randomly scattered over the inner surface. Almost immediately scores of scientists realized that many of the low viscosity fluids that worked well in packed columns were unsatisfactory for WCOT columns and should be replaced with high viscosity materials that would retain their high viscosity even at higher temperatures. Low-viscosity silicone fluids (e.g. OV 101) were replaced with high viscosity silicones (e.g. OV 30, a viscous paste-like silicone), and experimenters soon began producing much more stable columns.

1.4.2 The Positive Results of Patent Enforcement

The low quality of the Perkin Elmer WCOT columns and enforcement of their patent led many scientists to begin making their own columns for their own use. This caused investigators in many other fields, who would have preferred to purchase usable columns from an outside source and confine their research to some other field, to now have to make columns; scores of scientists were now studying and publishing on methods of pretreating, deactivating, and coating columns. Their combined results were responsible for many of the advances in column improvements, and they soon surpassed the results that had been generated by Perkin Elmer [17].

1.4.3 Mileposts in Coating WCOT Capillary Columns

Golay had coated his original glass open-tubular columns by completely filling them with a dilute solution of stationary phase in a low-boiling solvent, sealing one end, and then drawing the column, open end first, through an oven [18]. As used by Golay, the column could be coiled only after coating, a distinct drawback. The method was improved by Ilkova and Mistrykov [19], who coiled, and then filled the column and sealed one end. The open end of the filled column was fed into a heated oven by supporting the column on a rotating rod fitted with a drive roller at the entrance to the column oven, thus literally screwing the rest of the column into the oven.

Up until just a few years ago, all chemistry departments at the multicampus Universities of California system frowned on applied research, and chemistry department faculties drifting away from pure organic chemistry or pure physical chemistry rarely survived to tenure. Analytical chemistry was essentially forbidden. There were many faculty members scattered through various other departments who were analytical chemists, and eventually they formed a “Group in Analytical and Environmental Chemistry”, open to anyone in any department who had interests in the analytical side. At one time I chaired that group for several years and it still exists. At this time, my title was “Professor of Food Science and Technology and Chemist in the Experiment Station”. This had several advantages: for one thing, those with just the academic title worked nine months per year, while the Experiment Station operated eleven months a year. My department chairman tolerated what he called my “dabbling” in gas chromatography, but insisted that I should also be working on subjects ...