- 339 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reactions in the Solid State

About this book

The whole of Volume 22 is devoted to the kinetics and mechanisms of the decomposition and interaction of inorganic solids, extended to include metal carboxylates. After an introductory chapter on the characteristic features of reactions in the solid phase, experimental methods of investigation of solid reactions and the measurement of reaction rates are reviewed in Chapter 2 and the theory of solid state kinetics in Chapter 3. The reactions of single substances, loosely grouped on the basis of a common anion since it is this constituent which most frequently undergoes breakdown, are discussed in Chapter 4, the sequence being effectively that of increasing anion complexity. Chapter 5 covers reactions between solids, and includes catalytic processes where one solid component remains unchanged, double compound formation and rate processes involving the interactions of more than three crystalline phases. The final chapter summarises the general conclusions drawn in the text of Chapter 2-5.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

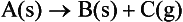

Application of the term decomposition to a chemical process is, in general, intended to signify the breakdown of one or more constituents of the reactant into simpler atomic groupings. Thermal decomposition is intended to imply that such reorganization is brought about by a temperature increase. (The word pyrolysis has the same meaning.) In this review, we are concerned with the thermal decomposition of solids. This term may be regarded as encompassing all processes which involve the destruction of the stabilizing forces of the crystal lattice of a reactant solid, including both chemical reactions and physical reorganizations (e.g. melting, sublimation and recrystallization). In general usage, a more restricted meaning of the definition has become acceptable and is specifically applied to those processes in which bond redistribution yields a solid residue of different chemical identity from that of the reactant. The thermal decomposition of a solid is, therefore, represented by

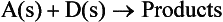

where A is the reactant, B and C are the product or products and (s) and (g) specify the solid and gaseous phases, respectively. Interactions between solids may, in general, be represented by

where the products may be solid, liquid and/or gaseous.

The thermal decomposition of a solid, which necessarily (on the above definition) incorporates a chemical step, is sometimes associated with the physical transformations to which passing reference was made above: melting, sublimation, and recrystallization. Aspects of the relationships between physical transitions and decomposition reactions of solids are discussed in a book by Budnikov and Ginstling [1]. Since, in general, phase changes exert significant influence upon concurrent or subsequent chemical processes, it is appropriate to preface the main survey of the latter phenomena with a brief account of those features of melting, sublimation, and recrystallization which are relevant to the consideration of thermal decomposition reactions.

Melting.: Loss of crystallinity of a solid reactant through melting, or eutectic formation, or dissolution in a product often results in an enhanced rate of decomposition as a consequence of the relaxation of the bonding forces responsible for lattice stabilization. The appearance of a liquid phase during the decomposition of solid reactants (e.g. metal nitrates or oxychlorides and organic substances) is often accompanied by an increased rate of product evolution. The presentation and discussion of observations for thermal decomposition reactions of solids should normally include due consideration of the possible occurrence of melting and the role of any liquid phase formed.

There is no generally acceptable comprehensive theory of melting. A feature of the fusion process, which is usually regarded as important in theoretical treatments of the subject, is the inability of a solid to superheat, and only a very small number of exceptions to this generalization are known [2]. This almost universal onset of liquefaction immediately upon reaching the melting point is in sharp contrast with the reverse process since supercooling of the vast majority of liquids can be demonstrated under appropriate conditions.

In a review of the subject, Ubbelohde [3] points out that there is only a relatively small amount of data available concerning the properties of solids and also of the (product) liquids in the immediate vicinity of the melting point. In an early theory of melting, Lindemann [4] considered that when the amplitude of the vibrational displacements of the atoms of a particular solid increased with temperature to the point of attainment of a particular fraction (possibly 10%) of the lattice spacing, their mutual influences resulted in a loss of stability. The Lennard-Jones—Devonshire [5] theory considers the energy requirement for interchange of lattice constituents between occupation of site and interstitial positions. Subsequent developments of both these models, and, indeed, the numerous contributions in the field, are discussed in Ubbelohde’s book [3].

Christian [6] treats melting as a nucleation and growth process, and discusses the possibility that the surface may be its own nucleating agent and lattice defects or impurities retained in such regions may similarly facilitate the formation of the melt. The melting process is, therefore, always effectively a two-phase phenomenon and any theoretical explanation must be based on consideration of the interactions between phases which differ in the degree of ordering.

Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf [7] provided a new theoretical approach in which melting was ascribed to the unrestricted proliferation of dislocations at the temperature for which the free energy of formation of glide dislocation cores becomes negative. Several physicists have shown interest in this model which has not so far been accorded similar attention in the chemical literature.

The theory of melting continues to be the subject of recent publications, including consideration of vacancy concentrations near the melting point [8,9], lattice vibrations and expansions [8, 10–12]. Meanwhile, the phenomenon also continues to be the subject of experimental investigations; Coker et al. [13], from studies of the fusion of tetra-n-amyl ammonium thiocyanate, identify the greatest structural change as that which occurred in the phase transition which preceeded melting. Solid and molten states of the salt are believed to possess similar structures, the significant difference being identified as the ability of the hydrocarbon chain to kink and unkink after fusion. The electrical conductivity of the solid increased as the melting point was approached. Allnatt and Sime [14] similarly found an anomalously large increase in the electrical conductivity of sodium chloride in the vicinity (i.e. within ∼4 K) of the melting point. Clark et al. [15] considered premelting transitions in the context of a general theory of disorder in plastic crystals.

As with other properties of solids, the increased relative significance of surface energy in very small (i.e. micrometre-sized) crystals influenced the melting points [2,16,17] and diffusion at this temperature. Quantitative studies of rates of melting of solids are impracticable since superheating is effectively forbidden and the rate of the endothermic phase change is determined by the rate of heat supply and the thermal conductivity of the solid.

Sublimation.: During sublimation, the lattice constituents of the solid are directly transferred to the gas phase without the intervention of liquefaction, though there may be mobile intermediates at the surface of the heated solid. Various features of the sublimation process have been reviewed by Somorjai [18] and by Rosenblatt [19] who included consideration of kinetic aspects. Rhead [20] has discussed diffusion processes at surfaces.

Recrystallization.: The recrystallization of a solid may result in the production of a higher temperature lattice modification, which permits increased freedom of motion of one or more lattice constituents, e.g. a non-spherical component may thereby be allowed to rotate. Such reorganizations are properly regarded as premelting phenomena and have been discussed by Ubbelohde [3]. The mechanisms of phase transitions have been reviewed by Nagel and O’Keeffe [21] (see also Hannay [22]).

Recrystallization may also result in the elimination of regions of local lattice distortion, e.g. dislocations, grain boundaries etc., without change in chemical composition or, indeed, lattice configuration: such behaviour has been described by Christian [6]. Where two phases are present, certain particles of the discontinuous phase may grow at the expense of other (smaller or less perfect) crystallites so reducing the total interfacial energy [23,24]. Reactions involving the precipitation of a new phase from supersaturated solution are of great commercial importance, e.g. carbide formation during the manufacture of ferrous alloys [25], and the crystallization of glasses [1246].

1 Characteristic features of decomposition reactions of solids

The main distinguishing features of reactions involving solids are that (i) the chemical transformation occurs within a restricted zone of the solid, characterized by locally enhanced reactivity (this zone is often referred to as the reaction interface); and (ii) where more than a single reactant is involved, solid products may constitute a barrier layer which tends to oppose further reaction.

Both of these mechanistic representations have been widely applied in interpretations of observations on solid state reactions and there is ample experimental evidence for their exis...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Comprehensive

- Front Matter

- Copyright page

- Comprehensive Chemical Kinetics

- Contributors to Volume 22

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Experimental

- Chapter 3: Theory of Solid State Reaction Kinetics

- Chapter 4: Decomposition Reactions of Solids

- Chapter 5: Reactions Between Inorganic Solids

- Chapter 6: Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reactions in the Solid State by Michael E. Brown,D. Dollimore,A.K. Galwey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Physical & Theoretical Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.