eBook - ePub

Human Papillomavirus

Proving and Using a Viral Cause for Cancer

- 460 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Human Papillomavirus: Proving and Using a Viral Cause for Cancer presents a steady and massive accumulation of evidence about the role of HPV and prevention of HPV-induced cancer, along with the role and personal commitment of many scientists of different backgrounds in establishing global relevance. This exercise involved years of personal commitment to proving or disproving an idea that aroused initial skepticism, and that still has difficult implications for some. It remains one of the big successes of medicine that exploited both established medical science dating back to the nineteenth century and new molecular genetic science during a time of transition in medicine.

- Presents a comprehensive, up-to-date review of the role of HPV in cancer from those involved in its study

- Includes the way evidence on the role and utility of HPV based prevention has been accumulated over almost 40 years

- Gives a series of vignettes of individual scientists involved in the development of the science of HPV and cancer at different stages and their experiences and reasons for involvement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Papillomavirus by David Jenkins,Xavier Bosch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Immunology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A Brief History of Cervical Cancer

David Jenkins, Emeritus Professor of Pathology, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom; Consultant in Pathology to DDL Diagnostic laboratories, Rijswijk, The Netherlands

Abstract

Cervical cancer is not a new disease. The history of how it was experienced, viewed, and managed in the past has been studied as a part of women’s history and the history of medicine and gynecology. The story is important for understanding how current knowledge developed and provides a link to how it is still seen in some societies outside the range of the modern Western medical tradition. This becomes very relevant to guiding attempts at global eradication.

Keywords

Cervical cancer; medicine; gynecology; tumor; Western medicine; screening

Cervical cancer is not a new disease. The history of how it was experienced, viewed, and managed in the past has been studied as a part of women’s history and the history of medicine and gynecology. The story is important for understanding how current knowledge developed and provides a link to how it is still seen in some societies outside the range of the modern Western medical tradition. This becomes very relevant to guiding attempts at global eradication.

The way in which diseases are defined and understood depends on the whole framework of ideas and customs that a society has developed, not just the doctors’ view or that of the patient. Cervical cancer has been for at least two millenia the archetypal “woman's cancer” because of its frequency and obvious unpleasnat symptoms.” The knowledge of the nature of cancer has, of course, changed hugely: clear pathological definition of cancer itself did not develop until the second half of the 19th century in a way that would be recognizable to modern medicine. Instead, the dominance of cervical cancer was a result of its frequent and dramatic, unpleasant, external manifestations of uncontrolled vaginal bleeding, and offensive discharge with severe pain and an often isolated death. Sometimes examination of the vagina would reveal ulcers and swelling, “tumor,” of the cervix to provide support for this diagnosis.

This led to cancer as a diagnosis, being seen as a “woman’s disease” before scientific autopsy provided better recognition of other cancers. The strict limitation of cancer to women also meant that the relationship of an almost entirely male medical profession to women’s encounter with cancer was complicated. The involvement of doctors was often limited to the very late stage of the disease when management of the illness within the home became impossible. Furthermore, midwives dealt with many of women’s reproductive problems and medical intervention in cervical tumors and ulcers was ineffective and sometimes fatal if a cure was attempted. Otherwise, it was limited to trying to relieve symptoms such as offensive discharge or pain.

It was not until pathology was extended from the 1830s by the application of the microscope to normal and abnormal tissues and cells that cervical cancer began to be defined more precisely. Right from the start microscopy was criticized for its solipsism and problems of reproducibility with arguments about its clinical utility, but nonetheless with Virchow’s Cellular Pathology published in 1858, there developed the foundations of modern understanding of the process of neoplasia and a definition of cancer based on tissue of origin and the behavior of cells. By the end of the century, pathologists were giving advice on whether a tumor should be removed, but even Virchow himself made misdiagnoses, very unfortunately in the case of the laryngeal cancer of Frederick III, Emperor of Germany. However, by the early 20th century, the definition of cervical cancer was now firmly based on microscopic pathology and not on symptoms, limited clinical examination, and ultimately the death of the unfortunate woman.

Understanding Cervical Cancer—From Paleopathology to the 19th Century

Papillomaviruses have been found to be the key to cervical cancer and some other important cancers within the last 40 years. However, modern phylogenetic research into the almost unlimited range of different papillomavirus genomes, the host specificity to many different animals and slow mutation rate has led to awareness that this virus family can be traced back for several hundred million years. It is therefore likely that cervical cancer, unlike cancers that are related to risk factors of the modern lifestyle, has been an important disease of women from prehistory. This gives a perspective that some types of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) have taken advantage of ordinary human sexuality as a part of their evolutionary approach to maintaining their existence, with unfortunate side effects for some humans, as is discussed in Section 1 of this book.

The problem with determining how long cervical cancer has existed with any certainty is that cancer of the cervix is unlikely to be reflected in purely skeletal remains, so most archeology is not that helpful, and retrospective diagnosis on mummies is often uncertain. There is a description of HPV in a genital warty lesion in a medieval mummy of an Italian Renaissance noblewoman who died in 1568, which was shown to contain HPV18 (Lancet 2003), but otherwise the early history relies entirely on the surviving descriptions of symptoms and signs, death as an outcome, and naked-eye appearances of cervical lesions by ancient medical authors. Cervical cancer, as we understand it today, was not really defined until the development of microscopic cellular pathology in the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century.

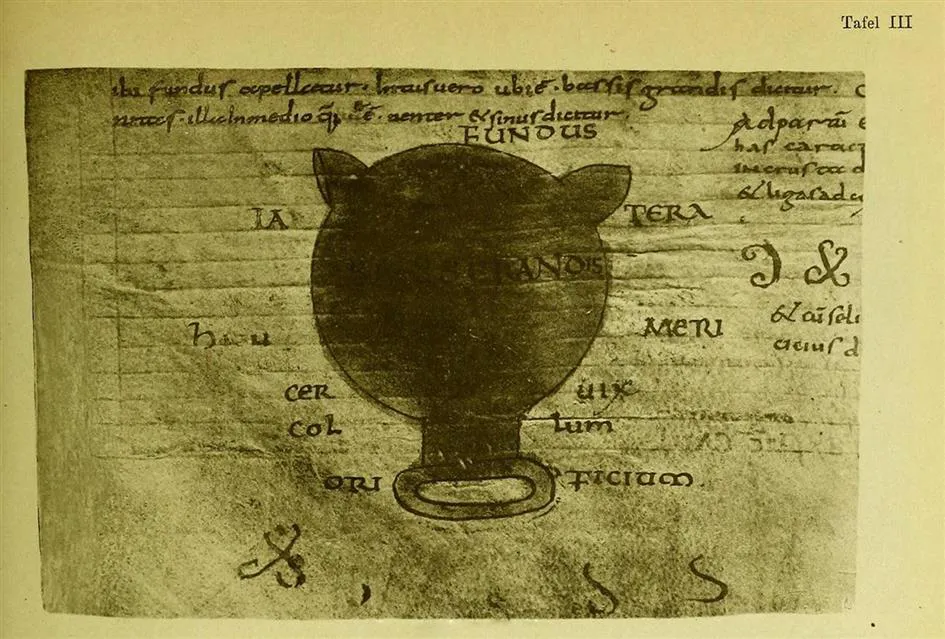

Nonetheless there are descriptions of probable uterine tumors in an Egyptian papyrus of 1700 BCE, and in the Hippocratic writings of the 4th century BCE. One of the most learned, critical and lucid, surviving, ancient texts is that of the Greek physician Soranus who was born in Ephesus, studied in Alexandria and eventually practiced in Rome in the early 2nd century CE. His Gynecology includes a description of a kind of vaginal speculum and also of cervical scirrhous and ulcerating lesions that almost certainly included cervical cancers (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). He was a “Methodist” eschewing the theoretical study of etiology and humoral ideas, but looking for patterns of disease rather than unfiltered experience. Other classical medical authors also discussed “malignant thymus” of the womb and Aetius of Amida (CE 502–575) summarized available information on “uterine chancres” and divided them into ulcerative and nonulcerative types. The Dutch surgeon Nikolaas Tulp (1593–1674) is credited with the first successful surgical removal of the cervix and Jean Astruc (1684–1766) described both pelvic inflammatory disease and “tumors of the cervix”—the distinction between benign and malignant growths being made using the patient’s ultimate fate. In the 17th and 18th centuries many drugs, including belladonna, strychnine and lead were applied to uterine tumors, but other doctors such as Herman Boerhaave treated these with milder substances.

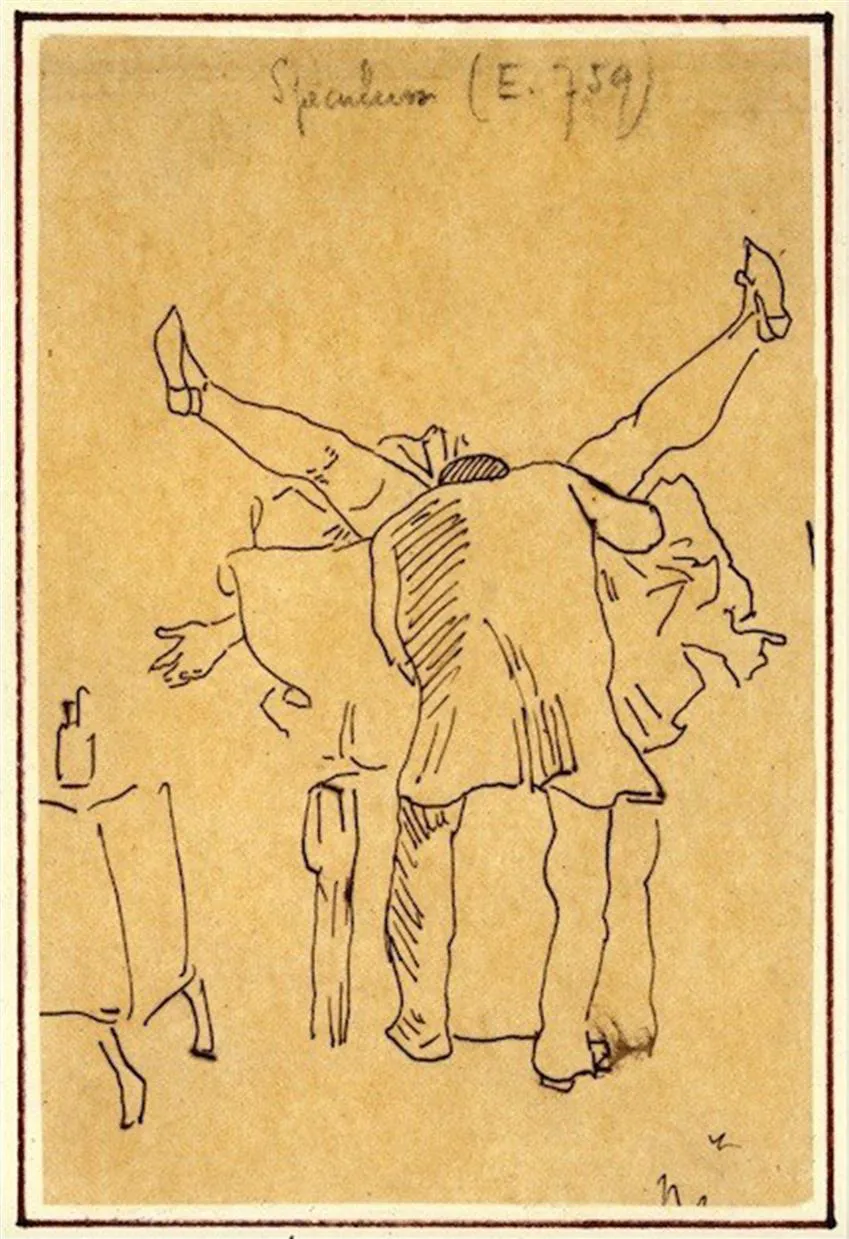

Transforming Western Medicine and the Rise of Medical Science

This picture of cervical cancer began to change with the development of morbid anatomy in the 18th century. The first drawing of a cancerous uterus appeared in Matthew Baillie’s The Morbid Anatomy of Some of the Most Important Parts of the Human Body in 1793, but whether this was cervical cancer is unclear. Doctors were interested in this new morphological approach but could not see the relevance to practice based on symptoms and trying to relieve them. In postrevolutionary France in the 1790s, the Paris school formed the basis of Western medicine in the first half of the 19th century, based on detailed observation of patients, routine autopsy, and the use of statistics. The French surgeon and gynecologist Joseph Recamier was credited as reviving the use of the vaginal speculum, although its main use was to detect venereal disease in prostitutes. The speculum was not permitted for midwives and its use linked to deviant female behavior, which made it an unwelcome symbol of male power for women (Fig. 1.3). Nonetheless, it provided the basis for the scientific development of gynecology, and the use of local treatments, although separation of scirrhous and ulcerating lesions from “true” cancer remained difficult.

Ideas on the origin of cancer were also developing. In 1806 the French doctor Auguste Rossignol explained that “the majority of experts agree that the cancerous virus is produced at the site of developments of this disease and infects the whole system only when it is carried through the circulation.” This was connected to the idea that cancer could be prevented or cured through elimination of lesions that might become cancerous. Opportunity for this was, however, limited by difficulties in diagnosing an early cancer from other “scirrhous” lesions.

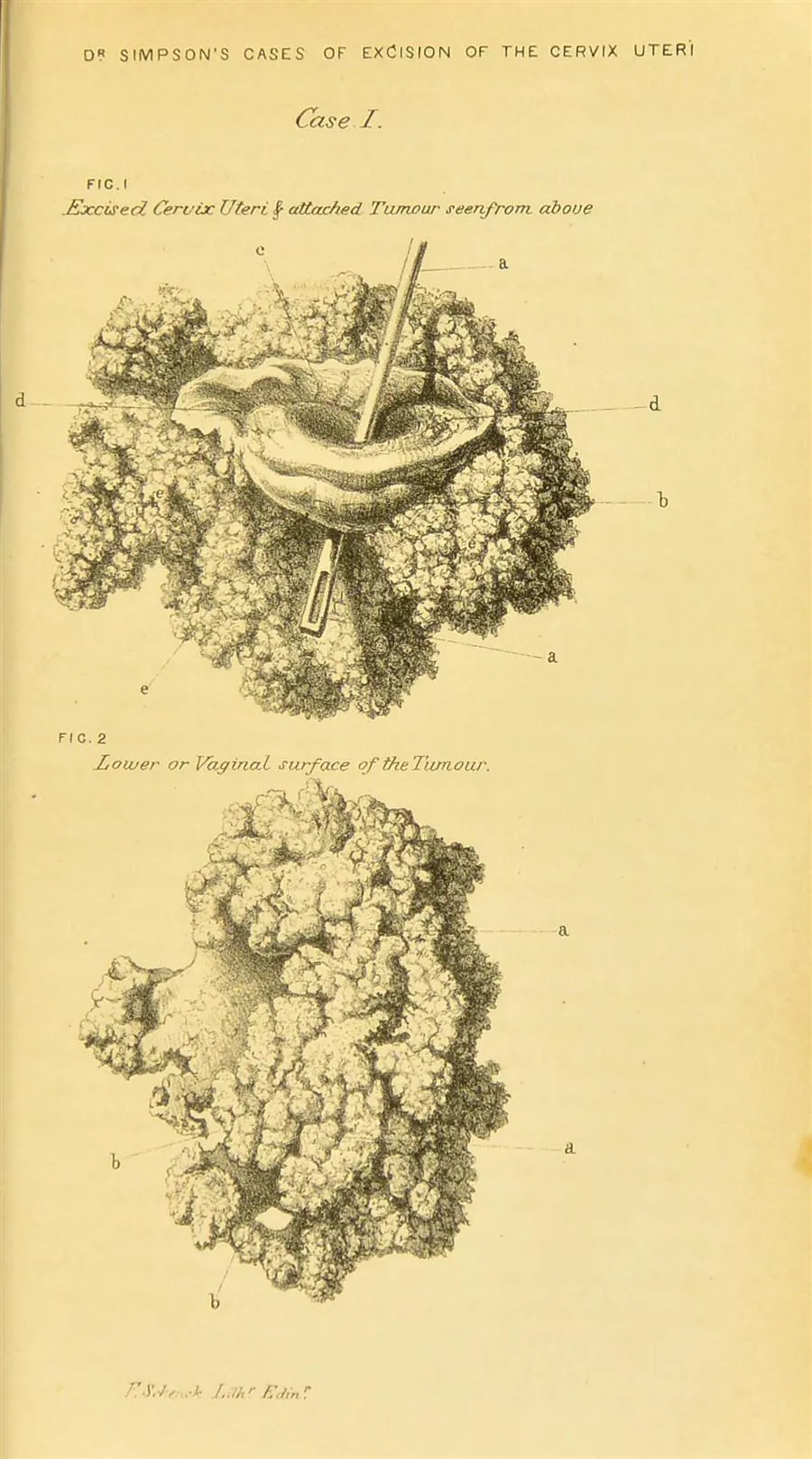

Although some “heroic,” painful, and often fatal surgery, cautery, and application of destructive chemicals took place in the treatment of suspect cancers, it was not until the development of anesthesia and antiseptic, then aseptic surgery that surgical treatment began to become more than occasional. Fig. 1.4 shows the surgical specimen of one excision of a suspect cervical cancer by the Victorian gynecologist, Sir James Simpson, a few years before he introduced anesthesia into obstetrics. Unfortunately, this might well be a giant condyloma not a cancer. The woman survived. The 1870s and 1880s were a period of rapid expansion of surgery. The German gynecologist Karl Schroeder (1838–87) recommended high amputation of the cervix; in 1878 Wilhelm Alexander Freund successfully removed a cancerous uterus by abdominal hysterectomy; and in 1891 Frederich Schauta proposed vaginal hysterectomy. This only carried a 25%–30% operative mortality compared to over 50% for more radical surgery. By the end of the 19th century hysterectomy had become the standard for tumors confined to the uterus, although there were few long-term survivals. In 1898 the Austrian gynecologist Ernst Wertheim introduced his radical abdominal hysterectomy, and within 10 years, he had reduced mortality from 20%–30% to 10%. Long-term survival was still only 10%–20% at 5 years but this was better than vaginal hysterectomy.

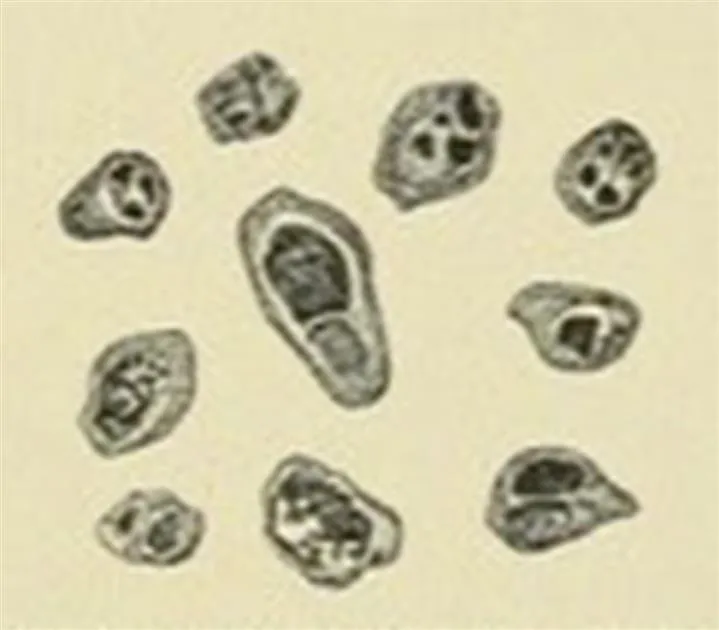

In the second half of the 19th century, cancer was becoming increasingly more precisely defined by microscopy. Following the approach of Rudolf Virchow, two doctors from the gynecological clinics of the University of Berlin, Carl Ruge and Johann Veit in 1880 analyzed tissues from women operated on by Karl Schroeder, found only half had confirmed malignancy and recommended biopsy before surgery. As well as defining the differences between endometrial and cervical cancer and showing the much higher frequency than of cervical cancer, the first description of carcinoma-in-situ emerged in 1886 by John Williams, and by the early 20th century, other such cases were being reported from time to time. There was interest in possible infectious causes of cancer, including protozoa (Fig. 1.5).

Soon after the discoveries of X-rays and of radium, in the early 1900s, they were being employed to treat gynecological malignancies as well as skin cancers. This introduced a new treatment with lower mortality than radical surgery, but with new and sometimes severe complications. It did not provide a complete solution.

The Idea of Prevention (Fig. 1.6)

In the 192...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- General Introduction—The Background to Human Papillomavirus and Cancer Research

- Chapter 1. A Brief History of Cervical Cancer

- Section 1: Proving the Role of Human Papillomavirus in Cervical Cancer: Studies in the Laboratory, Clinic, and Community

- Section 2: Human Papillomavirus Beyond Cervical Cancer

- Section 3: Using Human Papillomavirus Knowledge to Prevent Cervical and Other Cancers

- Section 4: Accumulating Long-Term Evidence for Global Control and Elimination of Human Papillomavirus Induced Cancers

- Epilogue: Looking forward to cervical cancer elimination

- Index