- 476 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Synthetic Membranes and Membrane Separation Processes

About this book

Synthetic Membranes and Membrane Separation Processes addresses both fundamental and practical aspects of the subject. Topics discussed in the book cover major industrial membrane separation processes, including reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, microfiltration, membrane gas and vapor separation, and pervaporation. Membrane materials, membrane preparation, membrane structure, membrane transport, membrane module and separation design, and applications are discussed for each separation process. Many problem-solving examples are included to help readers understand the fundamental concepts of the theory behind the processes. The book will benefit practitioners and students in chemical engineering, environmental engineering, and materials science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Synthetic Membranes and Membrane Separation Processes by Takeshi Matsuura in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Chemie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

NaturwissenschaftenSubtopic

Chemie1

Membranes for Separation Processes

Membranes for industrial separation processes can be classified into the following groups according to the driving force that causes the flow of the permeant through the membrane.

1. Pressure difference across the membrane is the driving force.

• Reverse osmosis

• Ultrafiltration

• Microfiltration

• Membrane gas and vapor separation

• Pervaporation

2. Temperature difference across the membrane is the driving force.

• Membrane distillation

3. Concentration difference across the membrane is the driving force.

• Dialysis

• Membrane extraction

4. Electric potential difference across the membrane is the driving force.

• Electrodialysis

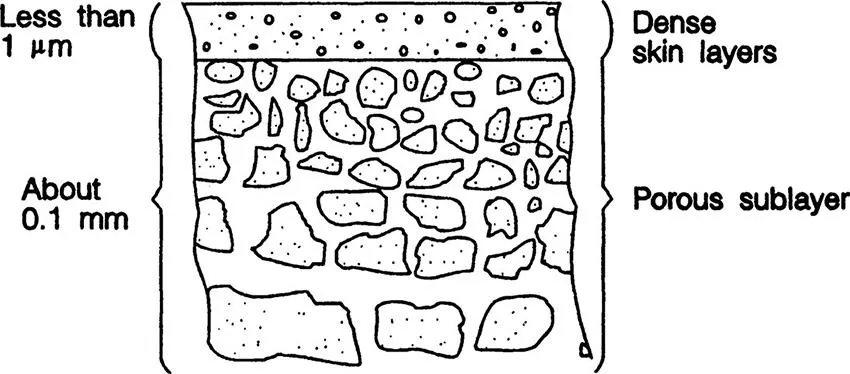

Reverse osmosis is a process to separate solute and solvent components in the solution. Although the solvent is usually water, it is not necessarily restricted to water. The pore radius of the membrane is less than 1 nanometer (nm) (1 nm = 10−9 m). While solvent water molecules, whose radius is about one tenth of 1 nm, can pass through the membrane freely, electrolyte solutes, such as sodium chloride and organic solutes that contain more than one hydrophilic functional group in the molecule (sucrose, for example), cannot pass through the membrane. These solutes are either rejected from the membrane surface, or they are more strongly attracted to the solvent water phase than to the membrane surface. The preferential sorption of water molecules at the solvent-membrane interface, which is caused by the interaction force working between the membrane-solvent-solute, is therefore responsible for the separation. Polymeric materials such as cellulose acetate and aromatic polyamide are typically used for the preparation of reverse osmosis membranes. Figure 1.1 illustrates schematically the cross-sectional structure of such membranes. A thin, dense layer responsible for the separation, and therefore often called an active surface layer, is supported by a porous sublayer that provides the membrane with sufficient mechanical strength. The entire thickness of the membrane is about 0.1 mm, while the thickness of the active surface layer is only 30 to 100 nm.

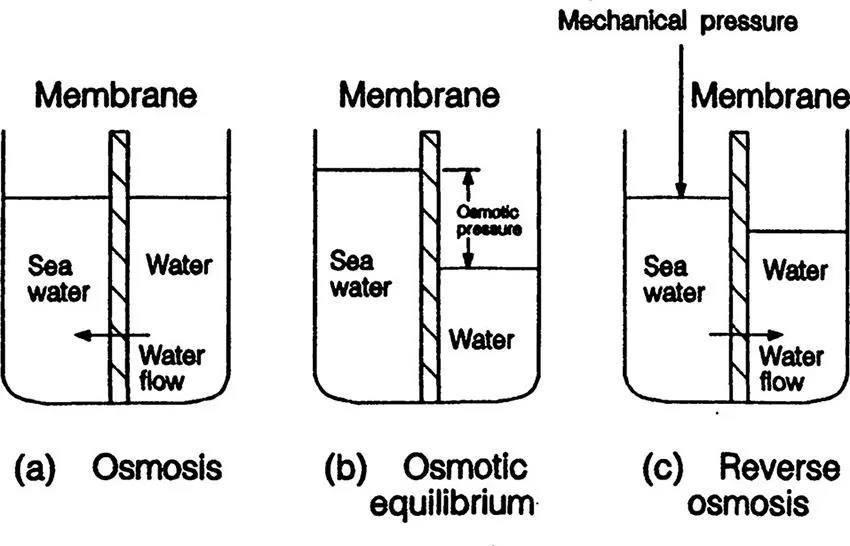

When a membrane is placed between pure water and an aqueous sodium chloride solution, water flows from the chamber filled with pure water to that filled with the sodium chloride solution, whereas sodium chloride does not flow (Figure 1.2a). As water flows into the sodium chloride solution chamber, the water level of the solution increases until the flow of pure water stops (Figure 1.2b) at the steady state. The difference between the water level of the sodium chloride solution and that of pure water at the steady state, when converted to hydrostatic pressure, is called osmotic pressure. When a pressure higher than the osmotic pressure is applied to the sodium chloride solution, the flow of pure water is reversed; the flow from the sodium chloride solution to the pure water begins to occur. There is no flow of sodium chloride through the membrane. As a result, pure water can be obtained from the sodium chloride solution. The above separation process is called reverse osmosis.

The most successful application of the reverse osmosis process is in the production of drinking water from seawater. This process is known as seawater desalination and is currently producing millions of gallons of potable water daily in the Middle East. Fishing boats, ocean liners, and submarines also carry reverse osmosis units to obtain potable water from the sea. In brackish water where the content of sodium chloride is much less than in seawater, lower osmotic pressures should be overcome for desalination. The reverse osmosis process is also being used to produce ultrapure water for the manufacture of semiconductors.

Ultrafiltration is a process based on the same principle as that of reverse osmosis. The main difference between reverse osmosis and ultrafiltration is that ultrafiltration membranes have larger pore sizes than reverse osmosis membranes, ranging from 1 to 100 nm. Ultrafiltration membranes are used for the separation and concentration of macromolecules and colloidal particles. Osmotic pressures of macromolecules are much smaller than those of small solute molecules, and therefore operating pressures applied in the ultrafiltration process are usually much lower than those applied in the reverse osmosis process. Membranes having pore sizes between those for reverse osmosis and ultrafiltration membranes are sometimes called nanofiltration membranes. The size of the solute molecules that are separated from water, and the range of operating pressures, are also between those for reverse osmosis and ultrafiltration. Ultrafiltration membranes are prepared from polymeric materials such as poly-sulfone, polyethersulfone, polyacrylonitrile, and cellulosic polymers. Inorganic materials such as alumina can also be used for ultrafiltration membranes.

Typical applications of ultrafiltration processes are the treatment of electroplating rinse water, the treatment of cheese whey, and the treatment of wastewater from the pulp and paper industry.

The pore sizes of microfiltration membranes are even larger than those of ultrafiltration membranes and range from 0.1 μm (100 nm) to several μ m. The sizes of the particles separated by microfiltration membranes are therefore even larger than those separated by ultrafiltration membranes. However, the separation mechanism is not a simple sieve mechanism whereby the particles whose sizes are smaller than the pore size flow freely through the pore while the particles that are larger than the pore size are stopped completely. In many cases the particles to be separated are adsorbed onto the surface of the pore, resulting in a significant reduction in the pore size. Particles can also be deposited on top of the membrane, forming a cake-like secondary filter layer. Therefore, the sizes of the particles that can be separated by microfiltration membranes are often much smaller than those of the pores in the “uncontaminated” membranes. Several methods are used to prepare microfiltration membranes. One of the methods is to sinter small particles made of metals, ceramics, and plastics. The spaces formed between the particles become the pores through which materials can be transported. A second method is to stretch a polymeric film. When a polyethylene film is stretched, part of the film becomes opaque. Pores are found in this part by electron micrographic observation. Another method is to irradiate a plastic film, such as a polycarbonate film, with an electron beam. Pores are formed when sections hit by the electron beam are chemically etched with a strong alkaline solution. The phase-inversion technique, in which the polymeric solution is cast onto a film and then solidified by immersing the film in a nonsolvent gelation bath, is also applied to prepare microfiltration membranes.

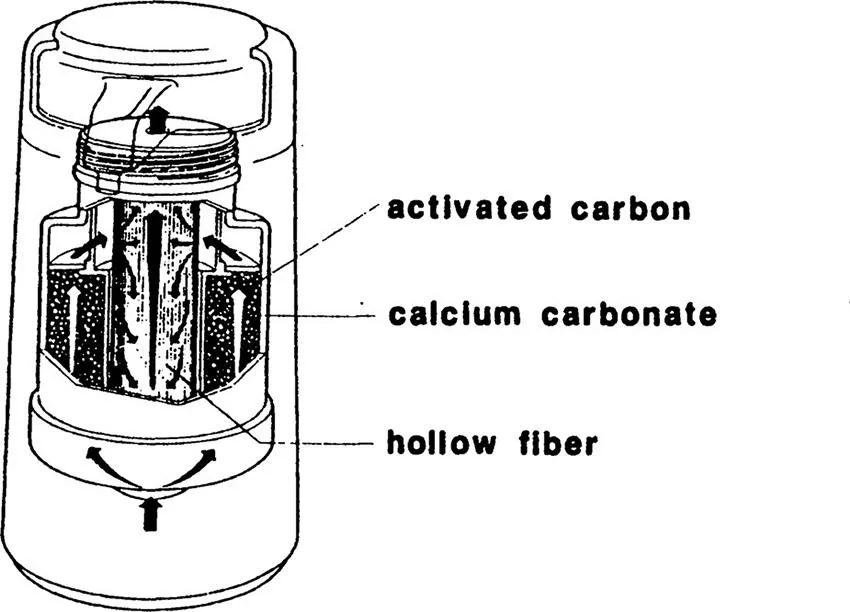

Microfiltration membranes are used for the removal of microorganisms from the fermentation product. For example, various antibiotics are produced by the function of microorganisms. Microfiltration membranes are used to separate the microorganisms from the product antibiotics. Microfiltration membranes are also used to remove yeast from alcoholic beverages. For example, in the process of producing draught beer, yeast is removed by membrane filtration. Recently, a cartridge for cleaning tap water was developed. Microfiltration hollow fibers made of polyethylene are combined in the cartridge with calcium carbonate and activated carbon columns, as illustrated in Figure 1.3. Small organic molecules, such as halogenated hydrocarbons, are removed by adsorption to activated carbon. Mineral and CO2 contents in water are increased while passing through a calcium carbonate layer. Finally, microorganisms, molds, and other turbid materials are removed by filtration with microfiltration hollow fibers.

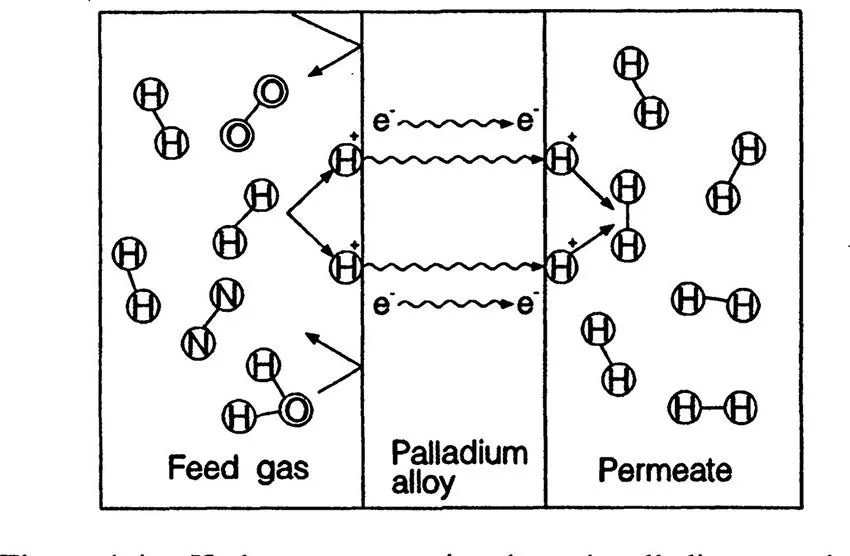

There are several types of membranes for gas and vapor separation. Palladium is known to absorb a large amount of hydrogen gas. One mol of palladium can absorb 6 mol of hydrogen. When the palladium alloy is stretched into a film, and a hydrogen pressure gradient across the membrane is applied, the transport of hydrogen starts to occur by this mechanism, illustrated in Figure 1.4. Hydrogen molecules are decomposed into atoms and adsorbed on the high-pressure side of the membrane. Then the electrons that surround the proton are transferred to the free electron band of palladium. The naked proton permeates the membrane from the high-pressure to the low-pressure side of the membrane and receives an electron at the low-pressure side of the palladium membrane, forming a hydrogen atom. Two hydrogen atoms are combined to form a hydrogen molecule, which leaves the membrane at the low-pressure side. Since the above transport mechanism works only for hydrogen gas, it can be used for the separation of hydrogen from other gases. The production of ultrapure hydrogen by palladium membranes is currently used in semiconductor industries. The separation and recovery of hydrogen from industrial exhaust gases that are rich in hydrogen also are important processes.

The properties of polymeric materials are similar to those of rubber, at temperatures above the glass transition temperature. Polymers in this state are called rubbery polymers. Usually, gas molecules permeate through the rubbery polymer very quickly because the binding force between molecular segments of the polymer is not strong, and segments can move relatively easily to open a channel through which even large gas molecules can pass. Therefore, the more the permeant molecule is sorbed to the membrane material, the faster the gas molecule can be transported through the polymeric membrane. Thus, volatile organic compounds, to which the polymeric material exhibits a strong affinity, permeate through a rubbery polymeric membrane much faster than do oxygen and nitrogen, even though the latter molecules are smaller. Membranes prepared from rubbery polymers can therefore be used to remove volatile organic compounds from air. A typical example of rubbery polymers is polydimethyl-siloxane.

When the temperature is below the glass transition temperature, the polymer is in a glassy state. There are regions where polymer segments are rigidly assembled in a crystalline form and also regions where they are loosely assembled in an amorphous form. The segmental motion of the polymeric molecule is, however, not as free as that of the rubbery polymer, even in the amorphous region, since the motion is restricted by the surrounding crystalline region. The size of the permeant molecule is a factor governing the permeation rate in the glassy polymer. Since hydrogen molecules have the smallest size, membranes prepared from glassy polymers can be used effectively for hydrogen enrichment. Carbon dioxide permeates through these membranes much faster than does methane, partly because a carbon dioxide ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Membranes for Separation Processes

- Chapter 2 Membrane Material

- Chapter 3 Membrane Preparation

- Chapter 4 Microscopic Structure of the Membrane and the State of the Permeant

- Chapter 5 Membrane Transport/Solution-Diffusion Model

- Chapter 6 Membrane Transport/Pore Model

- Chapter 7 Membrane Modules

- Chapter 8 Concentration Profile in a Laminar Flow Channel

- Chapter 9 Membrane Reactors

- Chapter 10 Applications

- References

- Appendix

- Index