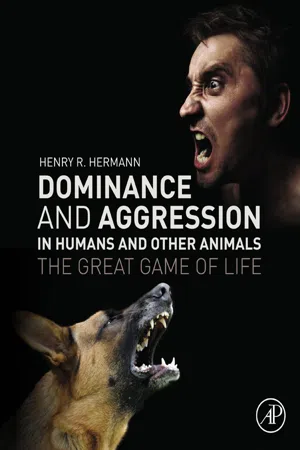

Dominance and Aggression in Humans and Other Animals

The Great Game of Life

- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Dominance and Aggression in Humans and Other Animals: The Great Game of Life examines human nature and the influence of evolution, genetics, chemistry, nurture, and the sociopolitical environment as a way of understanding how and why humans behave in aggressive and dominant ways. The book walks us through aggression in other social species, compares and contrasts human behavior to other animals, and then explores specific human behaviors like bullying, abuse, territoriality murder, and war. The book examines both individual and group aggression in different environments including work, school, and the home. It explores common stressors triggering aggressive behaviors, and how individual personalities can be vulnerable to, or resistant to, these stressors. The book closes with an exploration of the cumulative impact of human aggression and dominance on the natural world.- Reviews the influence of evolution, genetics, biochemistry, and nurture on aggression- Explores aggression in multiple species, including insects, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals- Compares human and animal aggressive and dominant behavior- Examines bullying, abuse, territoriality, murder, and war- Includes nonaggressive behavior in displays of respect and tolerance- Highlights aggression triggers from drugs to stress- Discusses individual and group behavior, including organizations and nations- Probes dominance and aggression in religion and politics- Translates the impact of human behavior over time on the natural world

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Defining Dominance and Aggression

Abstract

Keywords

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Biography

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- A Dominant Species on Planet Earth

- Chapter 1. Defining Dominance and Aggression

- Chapter 2. Traits of Dominant Animals

- Chapter 3. The Significance of Comparative Studies

- Chapter 4. Social Nonprimate Animals

- Chapter 5. From Whence We Came: Primates

- Chapter 6. The Human Animal

- Chapter 7. Similarities Between Humans and Other Living Organisms

- Chapter 8. Human Nature

- Chapter 9. Alternate Human Behavior

- Chapter 10. The Chemical, Physical, and Genetic Nature of Dominance

- Chapter 11. Dominance and Aggression in the Workplace

- Chapter 12. Dominance in Religion

- Chapter 13. Dominance in Politics

- Chapter 14. Human Aggression: Killing and Abuse

- Chapter 15. Killing Humans

- Chapter 16. Are We Our Own Worst Enemy?

- Chapter 17. Attempts to Save the Natural World

- Chapter 18. The Nature of Things

- Appendix

- References

- Glossary

- Index