1.1 Climate change and anthropogenic emissions of CO2

The surface of the Earth is about 33 °C warmer than would otherwise be the case because of the greenhouse effect, the name given to the natural warming of the planet as a result of absorption of infra-red radiation in the atmosphere. Without the greenhouse effect, the planet would be largely uninhabitable by humans (Solomon et al, 2007).

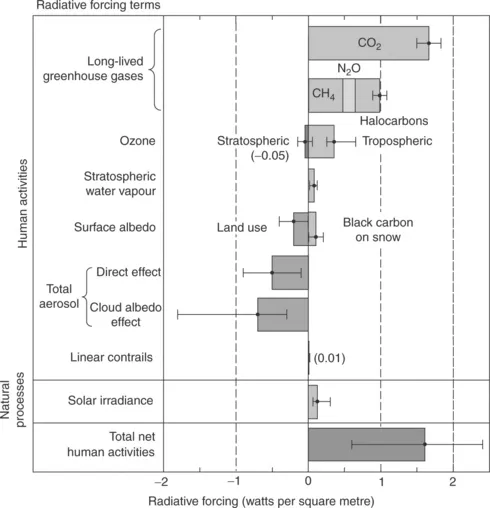

In recent years there have been many reports of changes in the Earth’s climate – the increasing frequency of unusually warm years, rising sea levels, the melting of snow, ice and permafrost in areas normally regarded as permanently frozen. Many of these changes are now widely recognised to be the result of the enhancement of the natural greenhouse effect by increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other gases, a phenomenon that was first predicted by Arrhenius more than 100 years ago (Arrhenius, 1896). These gases are the products of human activities – for example, the main causes of the rising level of CO2 in the atmosphere are the combustion of fossil fuels and deforestation (Peters et al, 2011). The concentration of CO2 reached 392 ppm in December 2011 (Tans and Keeling, 2012), compared with 320 ppm in 1965 (Keeling et al, 1976); the corresponding level before the industrial revolution would have been around 270 ppm. The contributions of the various gases to changing the greenhouse effect (more specifically, to changes in radiative forcing) over the past 250 years are illustrated in Fig. 1.1. The emissions of many of these gases continue to increase so further changes are expected.

Figure 1.1 The radiative forcing of climate due to various gases emitted between 1750 and 2005. Source: Reproduced with permission from Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, FAQ 2.1, Figure 2. Cambridge University Press.

What may happen to the climate is deduced from use of complex mathematical models of the atmosphere, called Global Circulation Models, coupled with models of terrestrial ecosystems and, most importantly, with models of the oceans. With emissions continuing to grow (Boden and Blasing, 2011), these models predict that global temperatures might rise by 3-4 °C by the year 2100 but there is considerable uncertainty in this figure, not only due to uncertainty about future emissions but also due to uncertainty about the sensitivity of the climate to increasing levels of greenhouse gases. After 2100, further change is expected and the rate of change may accelerate, something that provides even more cause for concern.

In order to avoid such changes in the climate, many actions have been proposed – to give some indication of what might be involved, calculations show that, if global emissions of greenhouse gases could be reduced by about 60% by 2100 compared with 1990 levels, the global temperature might be stabilised at 2 °C above 1990 levels by 2100 (with uncertainty of + 1/–0.7 °C) (Eickhout et al, 2003). However, global emissions have increased considerably since 1990 so it is now more realistic to consider that a target of 80% cut in current emissions might be needed to achieve such stabilisation. Although these figures are not at all certain, they help to illustrate the scale of the actions required if emissions are to be controlled sufficiently to halt the change in climate. Further reduction in emissions would be needed to reverse the changes in climate.

The models of the climate are hugely complex and, as indicated, are subjected to considerable uncertainty. Using them to make predictions about the future requires extrapolation beyond the range of data that has been used to build them which must add further uncertainty to the predictions. Further insight into how the climate may be changing, and a testing of the models, can be achieved by considering the state of the climate in prehistoric times.

1.1.1 The relevance of past geological periods for understanding climate change

Looking back to earlier periods provides information on the state of the planet when global temperatures and CO2 concentrations were higher than they are now, or have been in recent history. This allows testing of the climate models over a wider range of conditions. In this way it may also be possible to understand better why the climate changed in the past, which could increase confidence in the predictions of future changes.

A prime source of information on past states of the climate is the analysis of air trapped in polar ice and of the ice itself; such measurements give information on the condition of the prehistoric atmosphere (from which temperature can also be inferred) up to 650 000 years ago (Solomon et al, 2007). Before that time, other geological data can be used but there is greater uncertainty about such ancient atmospheric conditions. Nevertheless such data are important because they can be used to test climate models in conditions outside the range of the data from the ice measurements, in particular testing a key parameter, the sensitivity of the climate to CO2, which is difficult to do in other ways.

Some understandings about the climate in the past (Jansen et al,2007) include:

• Recognition that average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere during the second half of the twentieth century were higher than during any other 50-year period in the past 500 years. It is also likely that, in the Northern Hemisphere, the second half of the twentieth century was the warmest such period in the past 1300 years.

• The warming of the globe in the twentieth century has been about 10 times faster than any such change since the last period of maximum glaciation (21 000 years ago).

• There have been many other changes in the climate in the past, such as changes in the strength and frequency of El Nino-type events, abrupt changes in the strength of Asian monsoons, occurrence of droughts lasting for tens to hundreds of years in Africa and North America; these indicate that recent unusual events are not without precedent.

• Current atmospheric concentrations of CO2, CH4 and N2O are higher than for the past 650 000 years. Over that period, Antarctic temperatures have been closely related to atmospheric CO2 concentrations, although that does not prove which change caused what.

• In earlier periods (several million years ago) the Earth seems to have been warmer than at present. Indeed there were periods when it was mostly free of ice. The major expansion of Antarctic ice, which started around 35–40 million years ago, was likely due to declining CO2 levels from the peak in the Cretaceous era.

• Around 55 million years ago there was an abrupt warming of the planet and a large release of carbon into the atmosphere; this event lasted about 100 000 years; it is being studied now because it has some similarity with the rapid release of CO2 taking place at present.

• Going further back in time, the warmth of the Earth in the Mesozoic era (65–230 million years ago) was likely associated with high levels of atmospheric CO2. Major glaciations occurred around 300 million years ago which likely coincided with relatively low concentrations of CO2 (compared with the periods immediately before and after).

Such measurements show that the Earth’s climate can change substantially. In some periods of warming, CO2 levels have also been high but cause and effect is less clear. Nevertheless, the risk that changes due to hu...