Introduction

Threats to nations and their citizens—be they human made or natural—are often moments of crisis and can have huge impacts on individuals, communities, businesses, and societies. Preventing, mitigating, or supporting resilience in the face of such crises remains a major role for nation states. Yet we inhabit a world where nations may be replaced by networks and where threats are global in reach. How do the governmental and policy functions of nation states address such changes? How can they develop strategies to deal with threats to themselves and/or their neighbors? Importantly, how can the technologies that have created this globalized and networked world—information and communication technologies (ICT) as well as global travel and trade—provide tools to support such strategies? Or are these networks opening us up to new threats and dangers?

In this book we are concerned with the links between ICT and national security strategies. Overall the concern is with “national security”; however, that may be conceptualized. This book addresses contemporary understanding of national security and threats to national security, predominantly from those tasked with providing this security, or those providing academic and research support to these practitioners. It also addresses issues of technological development and design, information, and communication technology use as well as the threats that such new technologies bring to nation states.

It is interesting to note that journalist and writer Simon Winchester argued that the Internet was born in 1883 with the eruption of Krakatoa. The international telegraph network spread the news of this disaster around the world almost as fast as the sound waves from the explosion. This disaster also demonstrated the fragility of this fledgling global ICT network as the resultant earthquakes, tsunamis, and eruption cut undersea cables. We now live in a networked world and this reality needs to be part of our security planning and strategies.

National strategy and strategy formulation process

To discuss the notion of National Security strategy formulation process, it is essential to first define strategy, particularly at the national level. The concept of strategy originates from the military. The word derives from the Greek strategia, the office of the military council. It is commonly used in many domains to imply an overall plan or approach. Since the widespread adaptation of the concept of strategy by academics and practitioners in the 1950s, particularly in business and military schools, there has been a proliferation of research on “strategy.” Despite this, a general consensus about what strategy is has not been reached. Across a broad range of disciplines a variety of conceptual frameworks and methodologies have been developed for the formulation and implementation of “strategies.” All of these are based on different interpretations of the meaning of strategy. Some key examples include: Andrews (1971), Mintzberg (1976), Hofer and Schendel (1984), Porter (1985), Rainer (1989), Johnson and Scholes (1993), Stacey (1993), Thompson (1993), Levy (1994), Lynch (1997), Hussey (1998), and Wickham (2000). In this chapter we are not aiming for a critical evaluation of strategy as a concept, and we are not introducing various schools of thought on strategy or strategy formulation process. Instead, we are using a concept of strategy that is, in our view, more closely aligned to the notion of national security.

Nickols (2000) stated:

Strategy is at once the course we chart, the journey we imagine and, at the same time, it is the course we steer, the trip we actually make. Even when we are embarking on a voyage of discovery, with no particular destination in mind, the voyage has a purpose, an outcome, an end to be kept in view.

Based on this view, and that of Mintzberg (1976), we put forward the proposition that strategy at the national level can consist of the epistemological combination of proposition, perspective, position, results of an oriented long-term plan, and pattern. In essence national strategy is the bridge between governmental policy or high-order goals for maintaining and preserving national interests on the one hand and concrete actions on the other. In short, national strategy is a term that reflects an evaluable framework that provides specific guidance for specific actions in pursuit of a national interest by utilizing resources within dynamic local and global settings. This setting and the strategy that is cognizant to some degree of the complex web of thoughts, ideologies, visions, doctrines, ideas, insights, knowledge, legal and constitutional frameworks, experience, goals, expertise, values, perceptions, and expectations of those making, implementing, or impacted by the strategy. Importantly the strategy will reflect the collective mental constructs of those individuals in positions of power or responsibility with regard to the strategy. Nickols (2000) stated that strategy “has no existence apart from the ends sought.” This implies that the necessary precondition for formulating strategy is a clear and widespread understanding of the ends to be obtained. Without these ends in view, action is superficial and likely to lead to “strategic failure.” Thus national strategy formulation also can be defined as a pragmatic, action-oriented, and goal-driven process of transforming current national status (AS IS) to the desired status (TO BE) based on mental constructs (e.g., vision, values, and motivation) of individuals with governing and policy-making responsibilities. This has to take place within the constraints of relevant material, social, cultural, constitutional, and legal frameworks.

When considering national strategy, the following properties should also be considered:

• The time frame for implementation is usually medium to long term.

• The evaluation of the value of the impact of a national strategy should be based on the return on investment and return on capital employed; however, these may be consistently measured.

• Overall national strategy usually combines more functional strategies (e.g., defense strategy, financial strategy, and social and economic strategy), which also decompose to operational strategies (e.g., naval strategy, banking sector strategy, policing strategy).

• National strategy should support/shape a national competitive advantage or reduce its rivals’ competitive advantage. National strategy is not limited to geographical and territorial boundaries of a nation; therefore, the notion of competitive advantage should be considered at a global level.

Johnson and Scholes (1993) provided a framework (see Figure 1.1) for summarizing the key stages of strategic management. In the next section this view of strategy is adapted and applied in the context of a national strategy.

Figure 1.1 Elements of national strategy life cycle. (Johnson and Scholes, 1993).

At the heart of Johnson and Scholes’ (1993) framework lie three interconnected components:

1. Strategic analysis for understanding the strategic position of a nation

2. Strategic choice for generation of strategic options, evaluation of strategic options, and selection of strategy

3. Strategy implementation for the translation of strategy into action by considering national resources, legal and constitutional frameworks, and the management of deployment/implementation

The glue that provides the linkage between the three components is the strategic intelligence of the nation. This consists of all of the critical data, information, and knowledge needed for realization of the national strategy. Therefore the systems, platforms, and infrastructure that support or create such intelligence are considered one strategic national asset needed for realization of national strategy.

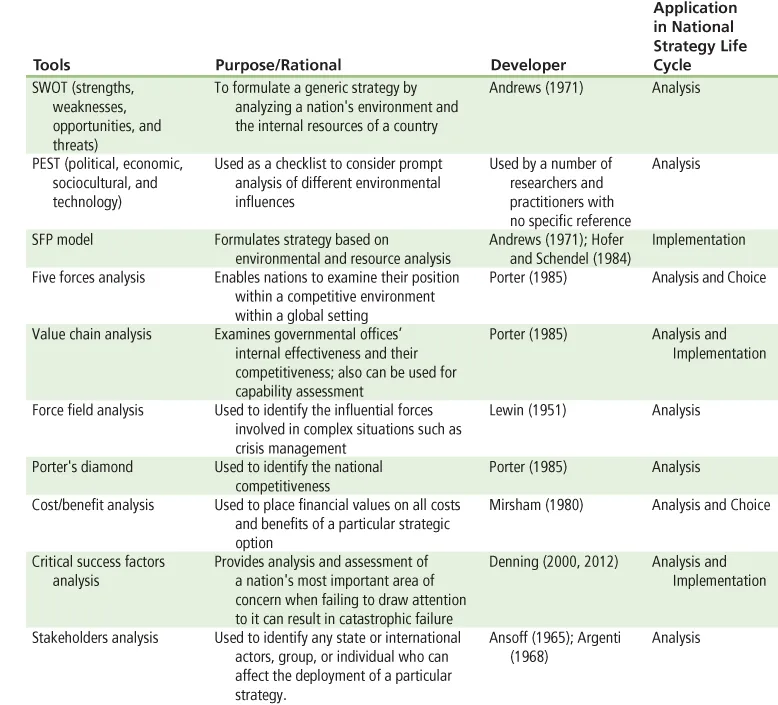

The realization of the above model requires a set of analytical tools that can aid the strategy formulation process. There are various tools and techniques that have been used in the strategy formulation process in military and business planning, and their application can be extended and adapted for a national strategy formulation process. A simple taxonomical classification can place their application into three categories:

1. Those who aid the analysis of the environment in which strategy is formulated

2. Those who identify choices, options, and alternative scenarios

3. Those tools and techniques that facilitate realization/implementation and evaluation of strategy.

Table 1.1 summarizes some of the most important (widely used) techniques, models, frameworks, and tools. Here we have to re-emphasize that the tools and models stated in Table 1.1 are only a sample representation, and in-depth evaluation of every tool and model stated in this table is outside the scope of this book. We have used a control vocabulary to adapt the application of these techniques, tools, and framework, for national strategy.

Tabel 1.1

Strategy Techniques, Models, Frameworks, and Tools

National security

The term national security has no universally accepted definition and concepts linked to it are often ambiguous with an emphasis on freedom from military threat. A common understanding of national security focuses on the protection of society and citizens against threat or risk by government or nation states. It is traditionally associated with military defense and the security services, and is often focused on a local level. The provenance of the concept of national security appears to be the U.S. National Security Act of 1947 that was in response to WW II. It is therefore unsurprising that much of the literature around national security focuses upon the American perspective. The National Security Act (1947) was considered legally ambiguous in part, although this was allowed for broad interpretation whenever issues were deemed to threaten the interest of the state (Romm, 1993). Although the National Security Act did include a realization that it was more than just military security, this was understated from the beginning (Paleri, 2008). The Clinton administration’s National Security Strategy for a New Century (1999) said:

Nearly 55 years ago, in his final inaugural’ address, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt reflected on the lessons of the first half of the 20th Century. ‘We have learned,’ he said, ‘that we cannot live alone at peace. We have learned that our own well-being is dependent on the well-being of other nations far away. We have learned to be citizens of the world, members of the human community.

Once again though this strategy similarly focuses on strong military might. The terrorist events of recent years (New York twin towers attack of 2001, Madrid bombing 2004, London 2005 metro bombing, Mumbai 2008, etc.) have forced governments to think about national security in a broader context than just military operations and issues of competitive advantage in armed forces. For example, the current UK national security strategy readily admits that the country faces a different and more complex range of threats and includes terrorism, cyber warfare, and natural disasters as examples. Current national security strategies have therefore had to expand to consider sophisticated antiterrorism strategy. This is of course especially true as domestic attacks have been made on civilians and there has been a greater diversity of potential threats across the globe (see UK National Security Strategy; HM Government, 2011).

Therefore, today’s national security st...