![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Boyun Guo, Shanhong Song and Ali Ghalambor

1.1 Overview

The first pipeline was built in the United States in 1859 to transport crude oil (Wolbert, 1952). Through the one-and-a-half century of pipeline operating practice, the petroleum industry has proven that pipelines are by far the most economical means of large-scale overland transportation for crude oil, natural gas, and their products, clearly superior to rail and truck transportation over competing routes, given large quantities to be moved on a regular basis. Transporting petroleum fluids with pipelines is a continuous and reliable operation. Pipelines have demonstrated an ability to adapt to a wide variety of environments including remote areas and hostile environments. Because of their superior flexibility to the alternatives, with very minor exceptions, largely due to local peculiarities, most refineries are served by one or more pipelines.

Man’s inexorable demand for petroleum products intensified the search for oil in the offshore regions of the world as early as 1897, when the offshore oil exploration and production started from the Summerland, California (Leffler et al., 2003). The first offshore pipeline was born in the Summerland, an idyllic-sounding spot just southeast of Santa Barbara. Since then the offshore pipeline has become the unique means of efficiently transporting offshore fluids, i.e., oil, gas, and water.

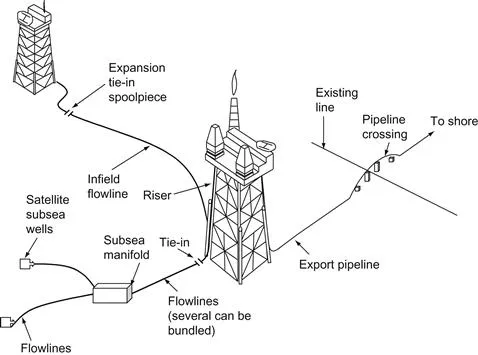

Offshore pipelines can be classified as follows (Figure 1.1):

• Flowlines transporting oil and/or gas from satellite subsea wells to subsea manifolds;

• Flowlines transporting oil and/or gas from subsea manifolds to production facility platforms;

• Infield flowlines transporting oil and/or gas between production facility platforms;

• Export pipelines transporting oil and/or gas from production facility platforms to shore;

• Flowlines transporting water or chemicals from production facility platforms, through subsea injection manifolds, to injection wellheads.

Figure 1.1 Uses of offshore pipelines.

Further downstream from the subsea wellhead, as more streams commingle, the diameter of the pipelines increases. Of course, the pipelines are sized to handle the expected pressure and fluid flow. To ensure desired flow rate of product, pipeline size varies significantly from project to project. To contain the pressures, wall thicknesses of the pipelines range from 3/8 in. to 1½ in.

1.2 Pipeline Design

Design of offshore pipelines is usually carried out in three stages: conceptual engineering, preliminary engineering, and detail engineering. During the conceptual engineering stage, issues of technical feasibility and constraints on the system design and construction are addressed. Potential difficulties are revealed and nonviable options are eliminated. Required information for the forthcoming design and construction are identified. The outcome of the conceptual engineering allows for scheduling of development and a rough estimate of associated cost. The preliminary engineering defines system concept (pipeline size and grade), prepares authority applications, and provides design details sufficient to order pipeline. In the detail engineering phase, the design is completed in sufficient detail to define the technical input for all procurement and construction tendering. The materials covered in this book fit mostly into the preliminary engineering stage.

A complete pipeline design includes pipeline sizing (diameter and wall thickness) and material grade selection based on analyses of stress, hydrodynamic stability, span, thermal insulation, corrosion and stability coating, and riser specification. The following data establish design basis:

• Reservoir performance

• Fluid and water compositions

• Fluid PVT properties

• Sand concentration

• Sand particle distribution

• Geotechnical survey data

• Meteorological and oceanographic data.

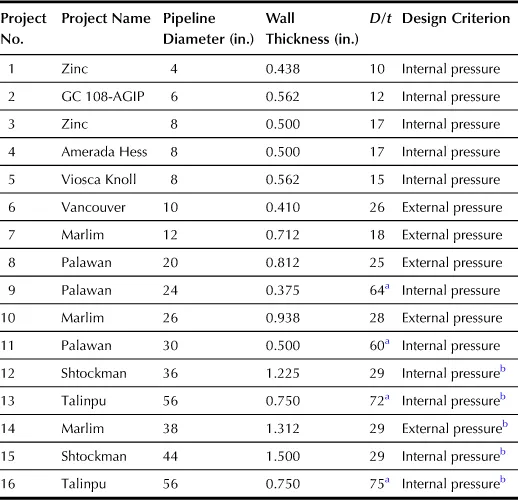

Table 1.1 shows sizes of some pipelines. It also gives order of magnitude of typical diameter/wall thickness ratios (D/t). Smaller diameter pipes are often flowlines with high design pressure leading to D/t between 15 and 20. For deepwater, transmission lines with D/t of 25–30 are more common. Depending upon types, some pipelines are bundled and others are thermal- or concrete-coated steel pipes to reduce heat loss and increase stability.

Table 1.1

Sample Pipeline Sizes

aPipelines with D/ t over 30.5 float in water without coating.

bBuckle arrestors required.

Although sophisticated engineering tools involving finite element simulations (Bai, 2001) are available to engineers for pipeline design, for procedure transparency, this book describes a simple and practical approach. Details are discussed in Part I of this book.

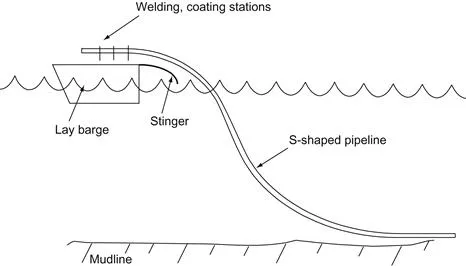

1.3 Pipeline Installation

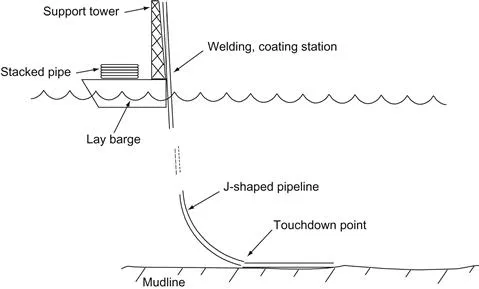

Once the design is finalized, pipeline is ordered for pipe construction and coating and/or insulation fabrication. Upon shipping to the site, pipeline can be installed. There are several methods for pipeline installation including S-lay, J-lay, reel barge, and tow-in methods. As depicted in Figure 1.2, the S-lay requires a laying barge to have on its deck several welding stations where the crew welds together 40–80 ft of insulated pipe in a dry environment away from wind and rain. As the barge moves forward, the pipe is eased off the stern, curving downward through the water as it leaves until it reaches the touchdown point. After touchdown, as more pipe is played out, it assumes the normal S-shape. To reduce bending stress in the pipe, a stinger is used to support the pipe as it leaves the barge. To avoid buckling of the pipe, a tensioning roller and controlled forward thrust must be used to provide appropriate tensile load to the pipeline. This method is used for pipeline installations in a range of water depths from shallow to deep. The J-lay method is shown in Figure 1.3. It avoids some of the difficulties of S-laying such as tensile load and forward thrust. J-lay barges drop the pipe down almost vertically until it reaches touchdown. After that, the pipe assumes the normal J-shape. J-lay barges have a tall tower on the stern to weld and slip prewelded pipe sections of lengths up to 240 ft. With the simpler pipeline shape, J-lay can be used in deeper water than S-lay.

Figure 1.2 S-lay barge method for shallow to deep pipelines.

Figure 1.3 J-lay barge method for deepwater pipelines.

Small-diameter pipelines can be installed with reel barges where the pipe is welded, coated, and wound onshore to reduce costs. Horizontal reels lay pipe with an S-lay configuration. Vertical reels most commonly lay pipe by J-lay method but can also use S-laying.

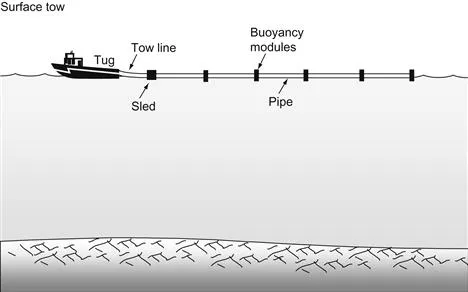

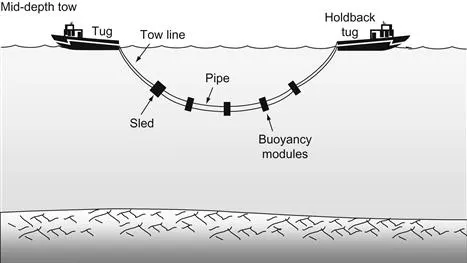

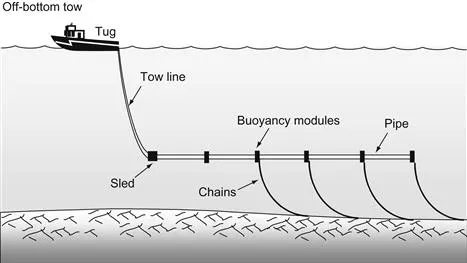

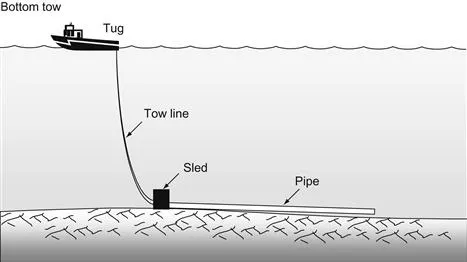

There are four variations of the tow-in method: surface tow, mid-depth tow, off-bottom tow, and bottom tow. For the surface-tow approach, as shown in Figure 1.4, buoyancy modules are added to the pipeline so that it floats at the surface. Once the pipeline is towed on site by the two towboats, the buoyancy modules are removed or flooded, and the pipeline settles to the sea floor. Figure 1.5 illustrates the mid-depth tow. It requires fewer buoyancy modules. The pipeline settles to the bottom on its own when the forward progression ceases. Depicted in Figure 1.6 is the off-bottom tow. It involves both buoyancy modules and added weight in the form of chains. Once on location, the buoyancy is removed, and the pipeline settles to the sea floor. Figure 1.7 shows the bottom tow. The pipeline is allowed to sink to the bottom and then towed along the sea floor. It is primarily used for soft and flat sea floor in shallow water.

Figure 1.4 Surface tow for pipeline installation.

Figure 1.5 Mid-depth tow for pipeline installation.

Figure 1.6 Off-bottom tow for pipeline installation.

Figure 1.7 Bottom tow for pipeline installation.

Several concerns require attention during pipeline installation. These include pipeline external corrosion protection, pipeline installation protection, and installation bending stress/strain control. Details are discussed in Part II of this book.

1.4 Pipeline Operations

Pipeline operation starts with pipeline testing and commissioning. Operations to be carried out include flooding, cleaning, gauging, hydrostatic pressure testing, leak testing, and commissioning procedures. Daily operations include flow assurance and pigging operations to maintain the pipeline under good conditions.

Flow assurance is defined as an operation that generates a reliable flow of fluids from the reservoir to the sales point. The operation deals with formation and depositions of gas hydrates, paraffin, asphaltenes, and scales that can reduce flow efficiency of oil and gas pipelines. Because of technical challenges involved, this operation requires the combined efforts of a multidisciplinary team consisting of scientists, engineers, and field personnel.

Technical challenges in the flow assurance operation include prevention and control of depositions of gas hydrates, paraffin (wax), asphaltenes, and scales ...