1.1 Energy supply and waste management

Energy supply and waste management are great challenges that humans have faced for millennia. Tremendous progress has occurred, yet these issues are still important today. To meet these challenges we must move to an atom economy where every atom is utilized in the best possible manner. To achieve this goal, a fundamental understanding of the underlying mechanisms and processes of energy and waste generation is necessary.

Demand for energy has increased rapidly in the last century. This will continue as the rate of consumption increases as people strive to improve their living standards. The requirement that the rate of energy consumption matches the rate of energy accumulation and conversion has led to a transition from wood (biomass) to coal to oil to natural gas: biomass needs to be grown, has to be harvested, dried and processed before use, coal needs to be mined, transported and processed before use and oil needs to be transported and refined before use, whereas gaseous fuels, which are ready to use immediately, only need to be transported. This trend in energy use – an increased emphasis on energy sources that are distributed and ready for immediate use with preferably no pre-processing – is expected to continue as populations spread out.

For thousands of years humans have had to take care of waste effectively and we will have to continue to do so if the human species is to survive. In fact, nearly all of societies’ health problems can be traced to insufficient treatment or management of waste. Initially, waste management was only concerned with human excrement and sewage. It has now transitioned to what we term municipal solid waste (MSW), which includes other non-hazardous solid waste and is also increasingly concerned with gaseous wastes, primarily CO2 but also CH4 and others (NOx, SOx, etc). In terms of the impact of waste on society, concern about the former as an emitted by-product or waste is increasing due to the threat of climate change associated with CO2 emissions into the atmosphere.

Energy and waste are intimately connected in many ways. One of the more challenging is the gaseous and thermal waste associated with energy use. That is, useful work can be extracted from heat energy but is limited by the Carnot cycle and thus must yield thermal waste. Currently 80% of the world’s energy is produced via combustion or gasification, thus there is gaseous waste (emissions) such as NOx, SOx, particulate matter and CO2.

A convergence of energy and waste is occurring as evidenced by the growth in conversion of landfill gas to energy (LFGTE) and landfill gas (LFG) to fuels and the growth of WTE (nearly 100 new plants in the past few years). New technology development is focused on the extraction of energy in the most efficient manner and from all possible sources while reducing waste from those processes. Nations that do not have entrenched energy generation infrastructures are aggressively pursuing generation from all indigenous sources, particularly waste and biomass. Production of energy at optimal conditions from these ‘alternative’ sources comes from understanding the underlying reaction sequences (mechanisms) that occur. This enables the technologies to be designed in the most efficient way, extracting the maximum energy possible simultaneously producing the minimum amount of waste.

After reuse and recycling there are only two methods that can manage waste by matching the rate at which it is generated. The two proven means for disposal are burying municipal solid waste in landfill or thermally converting it in specially designed chambers at high temperatures, thereby reducing it to one tenth of its original volume and simultaneously recovering materials and energy. The heat generated by combustion or gasification is transferred to steam, which flows through a turbine to generate electricity. This process is called waste to energy (WTE). It recycles the energy and the metals contained in the MSW while most of the remaining ash by-product can be beneficially used for the maintenance of landfill sites (in the US) or for building roads and other construction purposes (in the EU and Japan). Waste to energy reduces the volume of MSW by 90%; if the remaining ash is reused, this is a nearly ‘zero waste’ solution.

1.1.1 Global municipal solid waste (MSW) generation and disposal

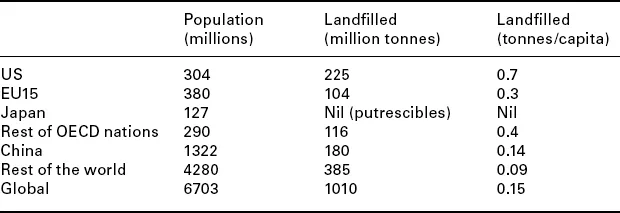

The economic development of the last century was accompanied by a greatly increased generation of solid wastes, which, when not managed properly, can adversely affect the environment and human health. In the generally accepted waste hierarchy adopted by USEPA and the EU, the first priority is waste reduction, followed by recycling of reusable materials, mostly paper fiber and metals, plus composting of fairly clean biodegradable yard and food wastes. In 2007, the Earth Engineering Center collaborated with NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies to produce a study on global landfill.1 More recent information2 on the amount of urban MSW landfill required in developing nations resulted in a downward revision of the global landfill to about one billion tonnes annually. This estimate is based on a combination of known tonnages landfilled in the US and other countries and interpolation to the rest of the world, as shown in Table 1.1. In comparison, the amount of MSW processed in thermal treatment facilities globally is estimated currently to be less than 200 million tons annually.3

Table 1.1

Estimate of MSW landfilled globally

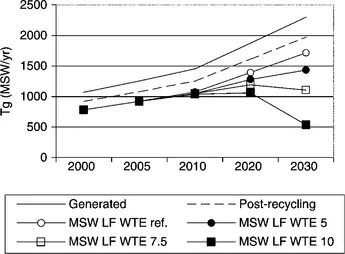

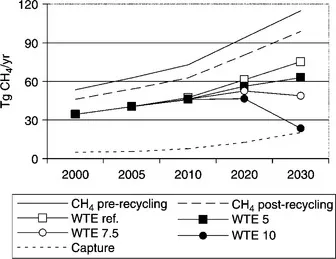

The study developed four scenarios for WTE growth, ranging from very conservative, where the 2000–2007 growth in capacity was assumed to remain at a constant rate of 2.5% through to 2030, to assumed increases in the rate of growth of WTE capacity of 5%, 7.5% and 10% per year in the period 2010–2030. The overall conclusion was that although global WTE capacity had increased by about 4 million tons per year in the period 2000–2007, to about 170 million tons, this rate of growth will not be enough to curb landfill methane emissions by the year 2030; population growth and economic development will result in a much greater rate of MSW generation and landfilling. The only way to reduce landfill greenhouse gases (GHGs) between now and 2030 is by achieving a 7.5% growth in thermal treatment capacity on a global scale, or by increasing the amount of methane captured at landfills (Fig. 1.1 and Fig. 1.2). To appreciate the greenhouse gas impact of global landfill, one needs to consider that according to the IPCC, one unit volume of methane emitted into the atmosphere has the same effect as 21 unit volumes of carbon dioxide.4

1.1 Generated and post-recycling MSW (constant for all scenarios) and landfilled MSW under four WTE scenarios.

1.2 Impact of WTE growth on net methane emissions from MSW. The solid line, the potential maximum, is included for reference only.

1.1.2 The hierarchy of sustainable waste management

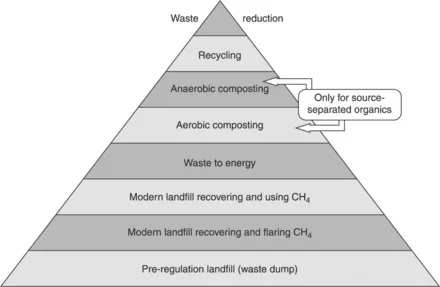

The BioCycle/Columbia bi-annual surveys in the US show that nearly 20% of US municipal solid wastes are recycled and about 10% are composted. As mentioned above, there are only two possible routes for the disposal of post-recycling wastes: thermal treatment with energy recovery, generally called waste to energy, and landfill. In the US, approximately 7% of the US municipal solid waste is used for WTE while the remainder (64% or 240 million tons) is landfilled. Figure 1.3 shows the expanded hierarchy of waste management, which differentiates between the best landfills, i.e. those that collect and utilize landfill gas, and the worst, which add to the greenhouse gas problem of the planet by emitting methane to the atmosphere.

1.3 The expanded hierarchy of waste management.*

WTE is an integral part of MSW treatment meeting global standards. In Europe, the preferred solution for the portion of MSW that is not recycled or reused is to combust the remainder in waste to energy facilities that generate electricity and recover steam, metals and other resources, with only about one-tenth of the original volume going to ash landfills or used for road construction and other uses.