![]()

Chapter 1

Macroecology of Sexual Selection

Large-Scale Influence of Climate on Sexually Selected Traits

Rogelio Macías-Ordóñez,1, Glauco Machado2 and Regina H. Macedo3, 1Red de Biología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, A.C., México, 2Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, 3Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Abstract

The exuberant variety of neotropical life forms has lured naturalists for centuries. Darwin himself was amazed by this diversity, and among the first to suggest that many of their traits were not the result of natural (viability) selection but rather of an additional and sometimes opposite selective force: sexual selection. Does this imply that sexual selection is stronger or acts differently in tropical environments? Although sexual selection is arguably the most studied evolutionary mechanism nowadays, a broad geographic perspective is seldom applied to answer this question. Our aim is to provide a theoretical framework to approach the study of sexual selection in a broad geographic scale using the Neotropics as a reference, highlighting the region’s great and frequently overlooked environmental diversity. We define “macroecology of sexual selection” as the large-scale influence of climatic conditions on sexually selected traits. Broad predictions are postulated concerning the effects of abiotic and abiotic factors that co-vary with latitude on life history, reproductive behavior, and sexually selected traits of arthropods, and of ectothermic and endothermic vertebrates.

Keywords

life history; climate types; sexual selection; neotropics; mating systems

Acknowledgment

This chapter was greatly improved by the suggestions made by Dr Robert Ricklefs, whose ongoing interest in and enthusiasm for the tropics is a source of inspiration to us all.

Introduction

The exuberant variety of life forms in the Neotropics, with their many shapes, sounds, smells, and colors, have lured naturalists for centuries. Darwin himself was amazed by this complexity (Darwin, 1862), and was among the first to suggest that many of these traits were not the result of natural (viability) selection, but rather of an additional and sometimes opposite selective force: sexual selection (Darwin, 1871). Does this imply that sexual selection is stronger in tropical environments? Or at least that sexual selection acts differently in the tropics when compared to more temperate or colder regions? Although sexual selection is arguably the most studied evolutionary mechanism nowadays, a broad geographic perspective is seldom applied to answer these kinds of questions. The aim of this chapter is to provide a theoretical framework to approach the study of sexual selection in a broad geographic scale using the Neotropics as a reference to compare what we know of sexual selection and reproductive strategies in this and other environments of the planet. In this chapter, we will postulate broad predictions concerning the effect of environmental factors on reproductive behavior and sexually selected traits of several animal groups, with the objective of stimulating research along these lines.

Defining the Neotropics

A strictly geographic definition of the Neotropics would exclude any area of the American continent north of the Tropic of Cancer and south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Yet the common perception for this region clearly extends beyond the 23° latitudes. The limits, though, vary widely depending on the criteria used when attempting a formal definition. On the one hand, the Neotropical Floristic Kingdom excludes southern South America and northern Mexico (Good, 1964; Takhtajan, 1969). On the other hand, Udvardy’s (1975) Neotropical Realm includes all of South America and the southern tip of Florida in the southeastern United States, but excludes not only northern Mexico but also the highlands of central and southern Mexico, Guatemala, and eastern Honduras. Biogeographical Realms were later adopted by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) with modifications as ecoregions (Bailey, 1998). A strictly climatic approach would include only those regions in the Americas with a tropical climate, defined as those areas with an average temperature of the coldest month above 18°C (Peel et al., 2007). This approach would lead to the inclusion of areas from the southern tip of Florida, in the southeastern United States, to Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Peru, but would exclude Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay altogether. A common concept in the literature is that the Neotropics equates to Latin America, encompassing the areas from Mexico southwards. This interpretation of what constitutes the Neotropics corresponds roughly to one of the eight biogeographic realms defined by Olson et al. (2001), but it excludes southern Florida while including temperate and cold regions of the extreme south of South America. This view was explored under a historical perspective in the Preface of the book.

As we hope will become clear, for the scope of this chapter and the rest of this book we really do not need to choose (and thus restrict ourselves to) one definition for the Neotropics; neither do we need to coin a new one. In fact, we will avoid discussing the limits of the Neotropics and focus on the patterns expected along environmental gradients. When addressing macroevolution at large geographical scales, Darlington (1958) suggested that “we do not need a full or precise definition (of the tropics), but one that will emphasize the significant differences between the tropics and the (north) temperate zone”. We are interested in the study of selective forces shaping reproductive behavioral, morphological, and physiological traits, and in order to do so we need to contrast environmental conditions shaping those forces. We have decided to use the Neotropics as a landmark or reference for this comparison for several reasons. This is the area we are most knowledgeable about, both from personal as well as professional perspectives, since it is where we carry out our research, and this is also true for almost all authors of this book. The Neotropics also encompass a region relatively well studied compared to other tropical regions of the world, although still relatively understudied when compared to most parts of the northern hemisphere (see below). Whatever limits we may adopt for the Neotropics, it is clear the region is far from homogeneous in terms of climatic conditions, landscapes, and vegetation types, and thus offers a great opportunity to explore how the action of sexual selection in different environments results in distinctive arrays of traits. Furthermore, we are interested in comparing what we know from the Neotropics with what we know from other regions. This yields the possibility of exploring a yet wider range of environmental variables, encompassing the greater wealth of research on sexual selection available from temperate and colder regions.

Tropical environments, as will be more formally defined later, present very different challenges and opportunities from those in more extreme latitudes (see review in Schemske et al., 2009). However, there is an oversimplified view of the Neotropics (and the tropics overall) that, in our opinion, severely constrains the potential to address macro-evolutionary patterns in broad environmental gradients. Although Darlington (1958) defined the tropics as “the zone within which, when other conditions are suitable, warmth and stability of temperature permit development of what we call tropical rain forest with its associated complex fauna”, the same author acknowledged that “many definitions are possible and no simple one is entirely satisfactory, for the tropics vary in climate (wet to dry), vegetation (rain forest to desert), and animal life”. We need an environmental framework with enough variability to accommodate predictions along environmental gradients, yet broad enough to be able to reflect nearly global trends. We have chosen to define this environmental framework using the current climate classification (Peel et al., 2007). Climate types provide an independent set of environmental variables that should cover major selective forces shaping sexual selection at a broad geographical scale.

Climatic Regions

A good place to start is the Köppen–Geiger climate classification (Table 1.1; Fig. 1.1). With few modifications, this climate classification has endured the test of time among climatologists and is now widely accepted as the standard in climatology (Peel et al., 2007). This section introduces this classification to the reader, as it is an important foundation point for the chapter. Climate has long been suggested as a powerful axis to address macro-evolutionary patterns (Darlington, 1958). Although “latitude” has more recently been used as a simpler proxy of climatic gradients (see, for example, Blanckenhorn et al., 2006; Schemske et al., 2009; Moya-Loraño, 2010), it will become evident in this chapter why, for our purposes, latitude is an oversimplification that does not allow predictions in specific combinations of environmental conditions, especially in such a rich mosaic of climate types as can be found within the Neotropics.

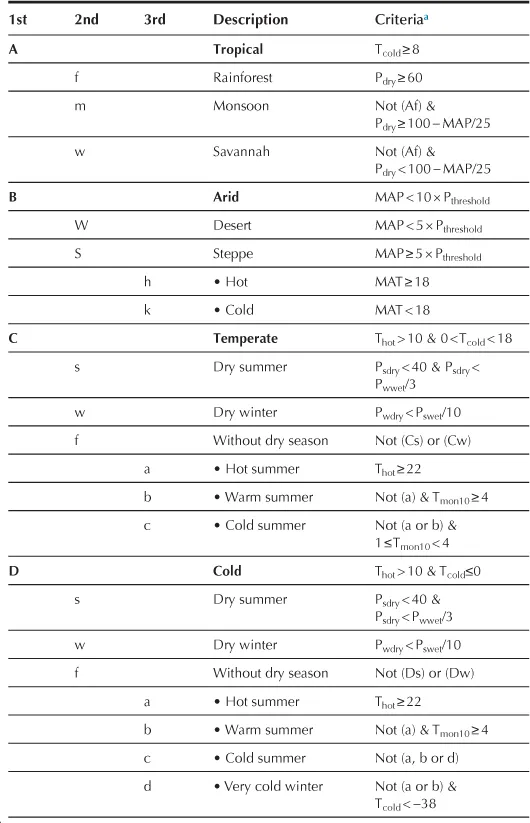

TABLE 1.1

Description of Köppen Climate Symbols and Defining Criteria (modified from Peel et al., 2007)

aMAP, mean annual precipitation; MAT, mean annual temperature; Thot, temperature of the hottest month; Tcold, temperature of the coldest month; Tmon10, number of months in which the temperature is above 10°C; Pdry, precipitation of the driest month; Psdry, precipitation of the driest month in summer; Pwdry, precipitation of the driest month in winter; Pswet, precipitation of the wettest month in summer; Pwwet, precipitation of the wettest month in winter. Pthreshold varies according to the following rules: if 70% of MAP occurs in winter then Pthreshold = 2 × MAT, if 70% of MAP occurs in summer then Pthreshold = 2 × MAT + , otherwise Pthreshold = 2 × MAT + 14. Summer (winter) is defined as the warmer (cooler) 6-month period of Oct–Nov–Dec–Jan–Feb–Mar and Apr–May–Jun–Jul–Aug–Sep.

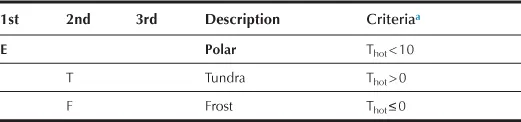

FIGURE 1.1 The Köppen–Geiger climate classification map (modified from Peel et al., 2007) and frequency of field studies on sexual selection in America and Europe (dotted line).

The area where each climate type occurs is expressed in millions of km2. For descriptions and criteria of each climate type, see Table 1.1. See color plate at the back of the book.

Although not entirely independent from biological factors, climate probably offers the most independent array of environmental variables defining plant (and thus biomes; Audesirk and Audesirk, 1996) and animal distributions, and thus key environmental factors of natural (viability) and sexual selection. The Köppen–Geiger climate classification is based on a nested set of climatic regimes defining 29 climate types identified by two- or three-letter combinations (Table 1.1). The first level is the broader climate classification of five climate types: tropical (A), arid (B), temperate (C), cold (D), and polar (E) (Peel et al., 2007; Fig. 1.1). With the exception of B (arid), all major climate types are defined using only temperature criteria.

As stated above, a tropical (A) climate includes those regions with monthly average temperature of the coldest month above 18°C. A second nested classification of tropical climate is defined by precipitation regime. The tropical rainforest climate (Af) is defined by precipitation in the driest month above 60 mm. The western Amazon basin is emblematic of this climate (Fig. 1.1). The tropical monsoon climate (Am) is defined by a somewhat more seasonal but still relatively humid driest month precipitation. The eastern Amazon basin, for instance, is characterized by this climate (Fig. 1.1). The tropical savannah climate (Aw) includes a severe dry season contrasting with a heavy rainy season. Most of southern Mexico and central Brazil have this climate type (Fig. 1.1).

The arid (B) climate is defined using a precipitation criterion and comprises regions with very low annual precipitation. A first division of this climate defines two different environments associated with two rain regimes: steppes (BS) and deserts (BW). Within those environments, a temperature criterion defines cold steppes (BSk) or deserts (BWk), and hot steppes (BSh) or deserts (BWh), depending on whether the mean annual temperature is below or above 18°C, respectively. A mosaic of the four different types of arid climate is characteristic of northern Mexico, the southwestern United States, the western slopes of the Andes in Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile, and the eastern slopes in Argentina (Fig. 1.1).

Temperate (C) and cold (D) climates are both defined by mean average temperature of the hottest month above 10°C, but a mean average temperature of the coldest month either above (C) or below 0°C (D), respectively. Both climates have the same two additional levels of subdivisions. The first level divides each of these climates based on precipitation regimes. Cf and Df do not have a well-defined dry season. Cw and Dw have a dry season during the winter, but a s...