eBook - ePub

Events of Increased Biodiversity

Evolutionary Radiations in the Fossil Record

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The fossil record offers a surprising image: that of evolutionary radiations characterized by intense increases in cash or by the sudden diversification of a single species group, while others stagnate or die out. In a modern world, science carries an often pessimistic message, surrounded by studies of global warming and its effects, extinction crisis, emerging diseases and invasive species. This book fuels frequent "optimism" of the sudden increase in biodiversity by exploring this natural phenomenon.Events of Increased Biodiversity: Evolutionary Radiations in the Fossil Record explores this natural phenomenon of adaptive radiation including its effect on the increase in biodiversity events, their contribution to the changes and limitations in the fossil record, and examines the links between ecology and paleontology's study of radiation.

- Details examples of evolutionary radiations

- Explicitly addresses the effect of adaptation driven by ecological opportunity

- Examines the link between ecology and paleontology's study of adaptive radiation

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Events of Increased Biodiversity by Pascal Neige in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Singular Work of Theater

Abstract

The history of biodiversity on the planet Earth could be compared to a work of theater. Biodiversity is a word which has been on the lips of many, often with a note of concern in the speaker’s voice. Yet what is biodiversity? The word simply denotes the variety of biological organisms. When you walk through a forest, when you dive into the sea, when you roam through a wheat field, relax on the beach or trek through a desert, you can see this biodiversity all around you. Almost by definition, it is not identical everywhere: sometimes ubiquitous, sometimes more discrete, but always present on (or near) the surface of our planet and in the oceans. It has been this way for a long time. For billions of years, even. Thus, biodiversity has a history – a very long one. In order to correctly and accurately analyze this biodiversity, it is necessary to look at its historical aspect, in context. With over 270,000 recorded species, flowering plants are, indubitably, a major part of the biodiversity present in the world today – all the more so when one considers that practically all vegetable material that we use in human foodstuffs comes from flowering plants. How come they are so diverse? When did this situation arise? Without understanding their diversification over the eons through geological records, we have no hope of accurately grasping the extent, nature and significance of their diversity today.

Keywords

Biomineralization

Diversification

Evolutionary radiations

Fossils

Mammals

Mass extinction

Natural selection

Precambrian/Phanerozoic shift

1.1 A unique history

The history of biodiversity on the planet Earth could be compared to a work of theater. Biodiversity is a word which has been on the lips of many, often with a note of concern in the speaker’s voice. Yet what is biodiversity? The word simply denotes the variety of biological organisms. When you walk through a forest, when you dive into the sea, when you roam through a wheat field, relax on the beach or trek through a desert, you can see this biodiversity all around you. Almost by definition, it is not identical everywhere: sometimes ubiquitous, sometimes more discrete, but always present on (or near) the surface of our planet and in the oceans. It has been this way for a long time. For an extremely long time. For hundreds of millions of years. For billions of years, even. Thus, biodiversity has a history – a very long one. In order to correctly and accurately analyze this biodiversity, it is necessary to look at its historical aspect, in context. With over 270,000 recorded species, flowering plants are, indubitably, a major part of the biodiversity present in the world today – all the more so when one considers that practically all vegetable material that we use in human foodstuffs comes from flowering plants. How come they are so diverse? When did this situation arise? Without understanding their diversification over the eons through geological records, we have no hope of accurately grasping the extent, nature and significance of their diversity today.

The idea I am attempting to put across in this book is a simple one: the story of biodiversity is, above all, a story of diversifications! Certainly, it is a story shot through with instances of extinction – sometimes by rather violent means. Yet the most striking feature of biodiversity is its incredible capacity for diversification. In scientific terminology, such diversification, when it is particularly significant, is called “evolutionary radiation”. This term will be used abundantly in this book. It is worth remembering: it denotes events of diversification of life on Earth. The study of evolutionary radiations is at the heart of this book.

Let us go back to the point made at the start of this chapter: the history of biodiversity on the planet Earth could, to a certain extent, be viewed as a work of theater. It has a beginning, a succession of “acts”, various actors – some at the head of the bill, and others with a more secondary role. Just like a play, the events take place against a changing backdrop. The position of the continents, the average sea temperature and the prevailing ocean currents are all elements of this “set” (among many others), which change over time. However, this resemblance with a work of theater is only superficial. Unlike a play, the story of biodiversity is not written in advance by a responsible individual. Indeed, it is not written in advance at all! It is, by its very nature, contingent. The events which occur on the evolutionary “stage” are primarily attributable to chance. A geological phenomenon, such as the opening of an oceanic rift, can give rise to changes in the environment which will play a role in the process of natural selection. Certain species encountering these new conditions will be able to adapt, whilst others will be driven to extinction. Those same species who do manage to adapt may then become extinct if the environmental conditions change again. The splitting of a geographic area into two – whatever the mechanism that causes it - may divide the population group of one species, and lead to the emergence of two new species. Random chance is a majorly important player in this work of theater. Thus, it renders the story entirely unique. Travel back in time, to the same exact conditions of the beginning of life on Earth, around 3.5 billion years ago, with the same actors and the same setting as before. Dim the house lights and raise the curtain, and let the action play out again. In all probability, you will see an entirely different story. This is the idea championed by Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002), a renowned American paleontologist [GOU 89]. Although there are clearly demonstrated mechanisms which help to shape biological evolution – of which natural selection is one example – it is nonetheless true that evolution is, by nature, contingent.

Today, numerous academics are engaged in imagining the evolution of biodiversity in days to come. These projections are made over relatively short periods of time, and use the same actors (the species which are around today) and the same elements of set (the present-day environment), which they alter in accordance with various scenarios. In 2009, for example, Cheung and his colleagues [CHE 09] calculated the effects of the climate changes likely to occur by 2050 on the distribution of over 1,000 species of marine animals (primarily fish). One of the lessons from this study is the prediction of numerous local extinctions of species in certain geographical zones – mainly the subpolar and tropical regions. Studies such as this one are increasingly prevalent in academia today. They enable us to better understand the effects that the coming environmental changes are likely to have on biodiversity. However, it must be noted that these studies are very greatly focused on the near future: projections over a few dozen years at most. Making projections beyond that remains a risky business – very risky, even. Unpredictable events (those which are, by nature, linked to random chance) may considerably impact the performance of the projection models.

However, the future state of Earth’s biodiversity is not the only issue worthy of interest. The biodiversity of the past is just as fascinating an object of study. The discoveries made by paleontologists looking at life in the past are far beyond what anyone could imagine. This exploration of the past helps answer the primary question of paleontology:

− what has been the history of life on our planet?

This central question invites other questions, some of which fit in entirely with the concerns of society today:

− what were the different actors that have played on that stage throughout the ages?

− how did some of those actors come to disappear?

− how does this past biodiversity illuminate what we know about biodiversity today?

− could the events of the past shed some light to help us better predict the future evolution of biodiversity on our planet?

Today, we can trace the outlines of the history of biodiversity thanks to fossils which bear witness to this past life. Fossils are the remains of ancient organisms or the traces of their activities: remnants in the form of bones, shells, teeth or traces of movement or predation, for example. Paleontologists discover and study fossils – not only to obtain a catalog of the most bizarre, most enormous or most ferocious forms of life, although this is an undeniably enjoyable activity! They study fossils in order to answer one of the greatest questions in modern science (posed a few lines earlier) what has been the history of life on our planet? Using their research, paleontologists reconstitute and order the different acts in that story, and the actors that have played out this singular piece of theater. It is by collecting fossils in the field that we are able to find out about the different actors. Yet this act of collection, however abundant, is not sufficient to precisely reconstruct the story. Paleontologists have only recently revealed their synthetic reconstructions of the history of life on Earth to the eyes of the public. By compiling the successive discoveries of fossils into gigantic databanks; by collating all pieces of paleontological information – the species found, their form, size, date of appearance and disappearance during geological eras, or indeed their habitat, paleontologists have collectively constructed a veritable civil register of the species which roamed our Earth throughout the ages: a sort of immense inventory which can be used to study the phenomena of biodiversity over the course of the different geological times.

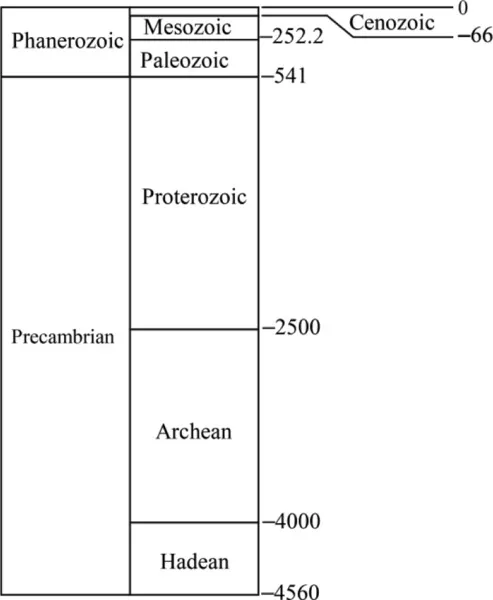

The primary result already demonstrated seems astoundingly simple: the biodiversity on our planet has not always been the same over the course of the geological times. Indeed, at times, it has been singularly different. Today, we know that life appeared on Earth around 3.5 billion years ago, and then endured in mainly microbial form for a very long period of around 3 billion years, a period called the Precambrian Era (see Figure 1.1 and also Tables A.1-A.5 for all the references to geological times). A more complex form of life emerged around 540 million years ago, at the junction between the Precambrian and the Phanerozoic Eon. At that time, intriguing organisms appeared. Some of them would die out, leaving no descendants. Anomalocaris, the largest predator in the oceans at the start of the Cambrian (at the very beginning of the Phanerozoic, 541 million years ago), which could grow up to a meter in length, had a particularly original morphology which has never been copied since: an elongated body with bilateral symmetry, with an articulated outer cuticle, a rounded mouth with triangular teeth and a pair of articulated, segmented front appendages reminiscent of the morphology of a prawn’s tail. This line of predators (feeding on hard- and soft-bodied organisms) would live for tens of millions of years, before finally dying out with no descendants.

Figure 1.1 Standard subdivision of the geological times. The ages are expressed in millions of years. Figure reproduced from [GRA 12]. Details on the Phanerozoic can be found in Tables A.1-A5

At that same boundary between the Precambrian and the Phanerozoic, anatomical elements never before seen appeared. Amongst other things, organisms invented the mineralized skeleton. They biomineralized! That is, they became capable of generating biominerals (e.g. to create a shell) – quite an invention! Shells, bones, carapaces, and indeed teeth, are examples of biomineralization which are entirely common today, but at the time, the emergence of biomineralization was a true revolution which would cause a seismic shift in the relations between organisms. This crucial period of the Precambrian/Phanerozoic shift, very rich in evolutionary events, also led to the establishment of most of the major body plans. These plans define the major categories of organisms by very particular anatomical traits, and characterize biodiversity as we know it today. Mollusks, arthropods, lophophorates, annelids, chordates and echinoderms are a number of kinds of organisms which emerged during this period. We shall come back to this point later on, in Chapter 4.

1.2 A story filled with catastrophes and recoveries

By examining the inventory of past forms of life, we have discovered repeating patterns in the evolution of biodiversity. Sometimes, the number of species dwindles rapidly. For example, 252 million years ago (at the boundary between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic Eras), we see a sharp drop in biodiversity. Around 95% of species were exterminated. The Permian–Triassic mass extinction was the most catastrophic of the crises that have befallen the Earth during its history. In the Phanerozoic, we estimate that five such major mass extinction events took place, with species extinction r...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- 1. A Singular Work of Theater

- 2. The Fossil Record

- 3. The Phenomenon of Evolutionary Radiation

- 4. Examples of Evolutionary Radiations

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index