- 446 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biomedical Foams for Tissue Engineering Applications

About this book

Biomedical foams are a new class of materials, which are increasingly being used for tissue engineering applications. Biomedical Foams for Tissue Engineering Applications provides a comprehensive review of this new class of materials, whose structure can be engineered to meet the requirements of nutrient trafficking and cell and tissue invasion, and to tune the degradation rate and mechanical stability on the specific tissue to be repaired.

Part one explores the fundamentals, properties, and modification of biomedical foams, including the optimal design and manufacture of biomedical foam pore structure for tissue engineering applications, biodegradable biomedical foam scaffolds, tailoring the pore structure of foam scaffolds for nerve regeneration, and tailoring properties of polymeric biomedical foams. Chapters in part two focus on tissue engineering applications of biomedical foams, including the use of bioactive glass foams for tissue engineering applications, bioactive glass and glass-ceramic foam scaffolds for bone tissue restoration, composite biomedical foams for engineering bone tissue, injectable biomedical foams for bone regeneration, polylactic acid (PLA) biomedical foams for tissue engineering, porous hydrogel biomedical foam scaffolds for tissue repair, and titanium biomedical foams for osseointegration.

Biomedical Foams for Tissue Engineering Applications is a technical resource for researchers and developers in the field of biomaterials, and academics and students of biomedical engineering and regenerative medicine.

- Explores the fundamentals, properties, and modification of biomedical foams

- Includes intense focus on tissue engineering applications of biomedical foams

- A technical resource for researchers and developers in the field of biomaterials, and academics and students of biomedical engineering and regenerative medicine

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Fundamentals, properties and modification of biomedical foams

Outline

1 Introduction to biomedical foams

2 Properties of biomedical foams for tissue engineering applications

3 Optimal design and manufacture of biomedical foam pore structure for tissue engineering applications

4 Tailoring the pore structure of foam scaffolds for nerve regeneration

5 Tailoring properties of polymeric biomedical foams

6 Biodegradable biomedical foam scaffolds

1

Introduction to biomedical foams

A. Salerno, Center for Advanced Biomaterials for Health Care (IIT@CRIB), Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Italy

P.A. Netti, Center for Advanced Biomaterials for Health Care (IIT@CRIB), Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Italy

Abstract:

Biocompatible and biodegradable foams are key components for tissue substitution for in vitro and in vivo tissue engineering applications, as well as for biosensing and diagnostic. The aims of this chapter are (i) to illustrate the evolution of the biomedical foam concept and its function from the beginning to the current applications; (ii) to provide an overview on traditional and advanced materials and processes for the design and fabrication of biomedical foams; and (iii) to describe some of the most important current applications of biomedical foams.

Key words

tissue engineering; bioactivated materials; biodegradable foams; biomedical foams; cell-instructive materials; microscaffolds; scaffold fabrication

1.1 Introduction

Due to their unique properties, porous materials have been widely used for biomedical applications requiring a three-dimensional (3D) porous network coupled with good mechanical properties, controlled degradation and biocompatibility. These applications include, among others: (i) porous biomedical devices and prostheses; (ii) scaffolds for in vitro cell culture and in vivo tissue-induced regeneration; (iii) macro-, micro- and nano-particulate foams for drug delivery, diagnostic and sensing, and, ultimately (iv) 3D culture platforms, for the investigation of cancer development and response to drug.

The performance of these biomedical foams – and therefore their field of application – resides in the sapient control over the different features and functionalities of the foams, which, in turn, depends on the appropriate selection of materials and fabrication processes. For example, in designing porous scaffolds for tissue engineering, the porous structure, including surface-to-volume ratio, pore size and interconnection degree, is a key factor in controlling cell behaviour and new tissue development (Karangeorgiu, 2005; Salerno et al., 2009a). Improving further the functionality of the foams integrating the control over cell fate through the spatial and chronological control of morphogen and growth factor delivery from the scaffolding material is now warranted (Sands, 2007; Biondi, 2008; Chan and Mooney, 2008).

Several processing techniques have been developed and are currently available for fabricating biomedical foams with specific control over their morphological, micro- and nano-structural features and degradation (Chevalier et al., 2007; Guarino et al., 2008). Furthermore, the advance in toxic-free and low-temperature processes allows for the controlled sequestration and release of bioactive moieties (LaVan et al., 2003).

Within the past decade, the ‘explosion’ of computer-aided approaches, microfabrication technologies and microfluidic strategies has noticeably increased the resolution achievable over biomedical foam architecture and composition (Hollister, 2005; Choi et al., 2007; Sands and Mooney, 2007; Melchels et al., 2010). This improvement has given an additional impulse in the biomedical field to elucidate several mechanisms underlying cell/material interactions and, ultimately, to develop multifunctional foams and scaffolds with improved performance.

At present, great efforts are being devoted to the design and fabrication of miniaturized foams with properties down to the nanometric scale that are able to combine technological potential with biochemical and biophysical cues. These multifunctional devices can serve different purposes, starting from building blocks for in vitro cell culture and in vivo tissue regeneration, to sensors and actuators to improve health status, and provide prophylactic or therapeutic treatment in situ.

This chapter aims to provide an overview of the history and evolution of biomedical foams, from the perspective of the materials, fabrication technologies and past, present and possible future applications.

1.2 Evolution of biomedical foams

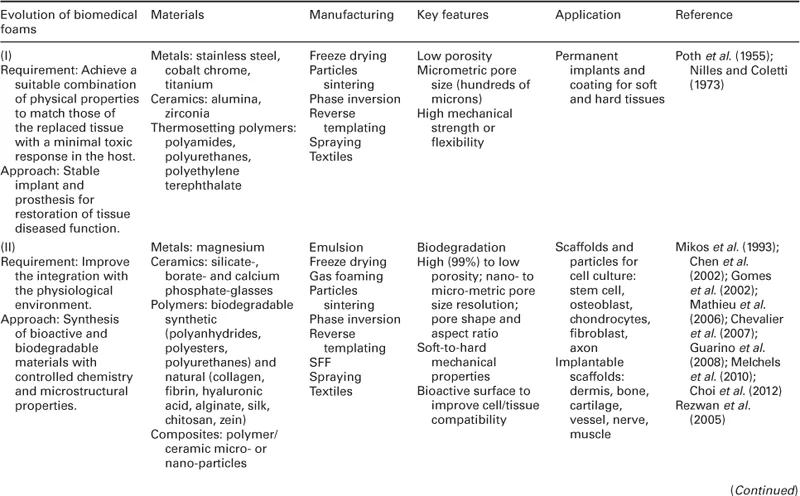

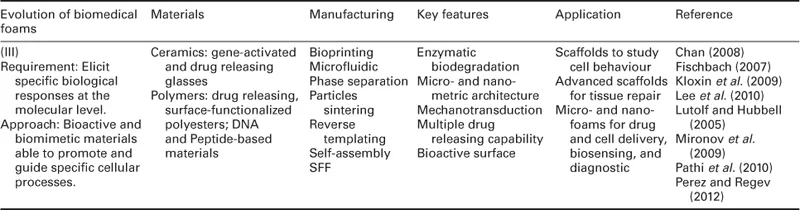

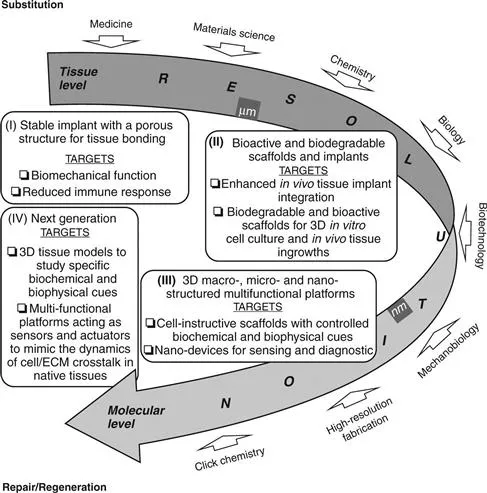

The history of biomedical foams started rather shortly after the discovery of the first implantable biomaterials. Biomaterials initially developed for use inside the human body were selected and designed in order to match the biophysical properties of the replaced tissue, and to induce a minimal toxic response by the host (Hench and Polak, 2002). Suitable implants were fabricated mainly from materials used and developed for different applications, such as metals, ceramics and thermosetting polymers, which ensured an adequate inertness when in contact with the body's aggressive environment (Table 1.1 and Fig. 1.1).

Table 1.1

Evolution of materials, fabrication, property and application of biomedical foams

1.1 Scheme of the evolution of biomedical foams from tissue substitution to repair/regeneration.

Recreating a porous structure on the surface of bone and vascular prosthetic devices was proposed to improve the bonding between prosthesis and surrounding tissues, and to overcome clinical problems related to implant mobility and stabilization (Poth et al., 1955; Nilles and Coletti, 1973). For instance, Nilles and Coletti (1973) demonstrated that bone prostheses characterized by open porous surfaces can induce tissue ingrowth at the interface and, therefore, improve their biomechanical performance as compared to non-porous ones. The efficacy of this approach is demonstrated by the fact that modern implants still follow this design principle and features.

Although inert foams allowed the fabrication of prostheses able to replace the mechanical functionality of tissues such as bone, the absence of biologically active surfaces render these materials unable to control the biological response at the interface between implant and surrounding tissue (Hench, 1998; Hench and Polak, 2002). As a direct consequence, an avascular, collagenous fibrous capsule that is typically 50–200 μm forms all around the implant, leading to several complications and, ultimately, to implant failure.

Improvement of biomedical foams occurred mainly between 1980 and 2000, when novel bioactive materials were developed with the aim of enhancing integration with the surrounding tissue. This was achieved by using, among others, bioactive ceramics and biodegradable polymers obtained from both synthetic and natural resources. The philosophy of these novel materials is that the body should no longer adjust to the materials, but that the materials should interact with the biological components, developing features that improve their response. An example of these materials are bioactive ceramics, such as bioglasses, that promote the in vitro and in vivo deposition and formation of a biological hydroxyapatite layer at the material surface, thus providing a biochemical bonding with the surrounding tissues (Hench, 1998). Bioglasses were used, for example, to coat the porous surface of metallic prostheses, which found clinical use in a variety of orthopaedic and dental applications (Cao and Hench, 1996).

Another advance was the development of biomaterials that exhibited clinically relevant chemical breakdown and degradation. These materials, mainly composed of biodegradable polymers and composites with ceramic particles, were engineered to provide a final solution to the foreign-body reaction, as they have the potential of being ultimately replaced by regenerating tissues (Hench and Polak, 2002).

The development of bioactive and biodegradable biomaterials in the 1980s coincided with the birth of tissue engineering science and the first significant paradigm shift of biomedical foams, from substitution to repair/regeneration (Fig. 1.1). During two decades, from 1980 to 2000, great efforts were devoted to designing 3D porous biodegradable substrates, named scaffolds, able to stimulate transplanted cells to regenerate biological tissues with defined sizes and shapes (Langer and Vacanti, 1993). In particular, the scaffold is intended as a three-dimensional temporary support for cells growth and proliferation, while its degradation and mechanical properties are tailored until the formation of a self-supporting newly generated matrix.

Collagen sponge was among the first scaffolds used in tissue engineering for the regeneration of skin-equivalent tissue of full thickness for the treatment of ulcers and acute wounds (Bell et al., 1981). Furthermore, porous scaffolds made of a wide range of synthetic and natural polymers, bioactive glasses and their composites were prepared, and their regeneration potential was assessed by using different cell lines and in vivo models. In particular, great effort was devoted to finding the optimal combination of scaffold composition, degradation rate, pore structure and mechanical properties for the repair/regeneration of tissues such as bone, cartilage, blood vessels, nerve and derma.

Most importantly, cultivating cells on porous scaffolds evidenced several technological problems related to in vitro cell seeding and survival within the 3D porosity. Indeed, inadequate fluid transport and cell viability inside cell/scaffold constructs may result in a necrotic core and the formation of inhomogeneous tissues. Technological approaches based on the use of bioreactors for dynamic cell seeding and cultivation represented a step forward to a more controllable and reliable in vitro tissue regeneration (Martin et al., 2004). Indeed, these bioreactors can improve cell distribution and colonization within the scaffold and, to date, are essential component of in vitro tissue engineering scaffold-based strategies.

The optimization of scaffold fabrication and culture conditions allowed new tissue synthesis both in vitro and in vivo. However, researchers observed that the biophysical and biochemical properties of these tissues were significantly different from those observed in native conditions. This was ascribed to the fact that cells in native tissues are exposed to a highly dynamic and complex array of biophysical and biochemical signals, originating from the extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM is the main regulatory and structural component of the tissues, and is composed of fibrous proteins, proteoglycans and glycoproteins (Chan and Mooney, 2008). The ECM signals are transmitted to the outside of a cell by various cell surface receptors and integrated by intracellular signalling pathways, finally regulating gene expression and cell phenotype (Lutolf and Hubbell, 2005). Then, the ultimate decision of a cell to migrate, proliferate, differentiate or perform other specific functions is regulated by this cell/ECM crosstalk. Furthermore, the bidirectional nature of this crosstalk, whereby a cell continuously modifies the properties of the ECM, stimulated further research towards developing scaffolds able to be remodelled by the cells. In particular, over the last decade the concept of cell guidance in tissue regeneration was discussed and revised, and new knowledge of the complex features of cell–material interaction has been disclosed and elucidated (Causa et al., 2007).

Advancement in chemistry, materials science and nanotechnology allowed s...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials

- Part I: Fundamentals, properties and modification of biomedical foams

- Part II: Tissue engineering applications of biomedical foams

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Biomedical Foams for Tissue Engineering Applications by Paolo Netti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biotechnology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.