eBook - ePub

Sea Otter Conservation

- 468 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sea Otter Conservation

About this book

Sea otters are good indicators of ocean health. In addition, they are a keystone species, offering a stabilizing effect on ecosystem, controlling sea urchin populations that would otherwise inflict damage to kelp forest ecosystems. The kelp forest ecosystem is crucial for marine organisms and contains coastal erosion. With the concerns about the imperiled status of sea otter populations in California, Aleutian Archipelago and coastal areas of Russia and Japan, the last several years have shown growth of interest culturally and politically in the status and preservation of sea otter populations.

Sea Otter Conservation brings together the vast knowledge of well-respected leaders in the field, offering insight into the more than 100 years of conservation and research that have resulted in recovery from near extinction. This publication assesses the issues influencing prospects for continued conservation and recovery of the sea otter populations and provides insight into how to handle future global changes.

- Covers scientific, cultural, economic and political components of sea otter conservation

- Provides guidance on how to manage threats to the sea otter populations in the face of future global changes

- Highlights the effects that interactions of coastal animals have with the marine ecosystem

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter 1

The Conservation of Sea Otters

A Prelude

Shawn E. Larson1 and James L. Bodkin2, 1Department of Life Sciences, The Seattle Aquarium, Seattle, WA, USA, 2US Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, AK, USA

The story of sea otters over the past 275 years chronicles their decline to near extinction and the roads to recovery that cross various conflicts, and in the end provides lessons that will aid the conservation of other threatened species and compromised ecosystems. Sea otters inspire strong human emotions ranging from adoration to disdain. They are protected internationally, federally, and at state and local levels, yet still face a diversity of threats, representing the legacy of their decline as well as emerging consequences from the ever-deepening imprint of the human endeavor. Here we briefly introduce the species, chronicle its history of near-demise and subsequent recovery, and highlight several conservation successes and challenges. In this volume we bring together scientists with significant knowledge of and experience with the sea otter and its ecosystems to share lessons learned and consider how these might be used to aid in the enterprise of conservation more broadly.

Keywords

Sea otter; Enhydra lutris; maritime fur trade; apex predator; keystone species; conservation; ecology; biology

Sea otters have come to symbolize the wonderful exuberance of nature as well as the tension among species competing for survival. Their remarkable hunting skills and huge appetites give them the capacity to alter the ecological balance of a small bay or inlet, while they are themselves vulnerable to the larger impacts of other predators, most notably humans. Our fascination with this remarkable species draws us to better understand them and the oceans on whose health we all depend.

Bob Davidson, CEO, Seattle Aquarium

Introduction

Over the past several centuries, expanding human populations have played an ever-increasing role in the diminishment and extinction of species, primarily through direct exploitation and alteration of habitats and ecosystem structure. Virtually nowhere on earth remains without the footprint of humans and, in most instances, that footprint comes with adverse consequences to resident species and ecosystems. The quest to regain functioning ecosystems and restore species presents one of the great challenges to humanity, and provides an opportunity for leadership by the science and conservation communities.

The sea otter, Enhydra lutris [L., 1758], and the coastal waters of the North Pacific provide an excellent example of both the adverse effects of human intervention and the positive effects of conservation and management directed toward restoration of species. Sea otters face many challenges because their unique history, biology, and nearshore habitat place them in close proximity to, and often in adverse interactions with, humans. The story of the sea otter ranges from extreme population decimation due to overharvest during the maritime fur trade to near complete protection and active conservation efforts, resulting in recovery of many sea otter populations over the past century. The sea otter may be one of the most widely studied and intensively managed marine mammals. It has been said that “if science can’t save the California sea otter population, science probably can’t save anything” (VanBlaricom, 1996). In this book we explore the science behind sea otter conservation and management and highlight lessons learned that may benefit other species and ecosystems.

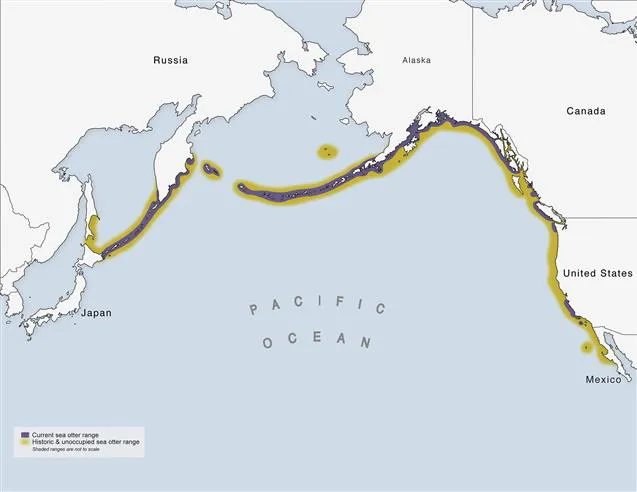

Following more than two centuries of a largely unregulated harvest for their fur, sea otters were on the precipice of extinction in the early twentieth century. By this time their population numbers were so low (estimated at <1% of pre-harvest abundance) and so widely dispersed that they could no longer support commercial harvest at any level (Kenyon, 1969). A population that once numbered perhaps several hundred thousand and extended from Japan along the North Pacific Rim to Mexico was reduced to perhaps a few hundred individuals in isolated groups, mostly in the far north of their range. Although occasional illegal and legal harvests are noted in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century (Hooper, 1897; Anonymous, 1939; Lensink, 1960), the international Pacific maritime fur trade is widely recognized as ending in 1910 (Kenyon, 1969; Chapter 3). Subsequently, sea otter populations began the slow process of recovery in the early twentieth century, (Lensink, 1962; Kenyon, 1969; Chapter 14). In 1965, Kenyon (1969) estimated the global sea otter population at about 35,000 animals, mostly in Alaska. At that time, more than 3000 km of habitat remained unoccupied between California and the Gulf of Alaska (Figure 1.1). Early attempts to translocate otters into unoccupied habitat in Russia and the United States beginning in 1937 were largely unsuccessful (Barabash-Nikiforov, 1947; Kenyon, 1969) but provided valuable experience that would aid in the success of future reintroductions (Chapter 8). From the 1960s through the 1980s, independent and international efforts were conducted to aid the recovery of sea otters through a series of translocations from Alaska to Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, and within Alaska and California (Chapter 3). The translocations re-established several populations and contributed to restoring some of the genetic diversity lost from harvest-induced population bottlenecks (Chapter 5).

The eventual conservation and restoration of sea otters was facilitated by three events that took place in the twentieth century: (1) the cessation of nearly all commercial-scale fur harvest early in the 1900s, (2) increased legal protections at state and national levels, and (3) the establishment of several translocated colonies along the west coast of North America late in the twentieth century that in 2013 represented more than one-third of the global sea otter population. In chapter 3 Bodkin provides a more complete description of the maritime fur trade and the process of recovery early into the twenty-first century. While Nichol (Chapter 13) and VanBlaricom (Chapter 14) describe sea otter conservation in practice in North American and the various legal protections enacted to restore sea otters in US waters.

In the twentieth century the spatial and temporal pattern of sea otter recovery provided significant research opportunities, as prey assemblages and coastal food webs were transformed during recovery of sea otter populations. Observations acquired over decades of research led to improved understanding of the role of sea otters, and by extension other apex or top predators, in supporting the form and function of ecosystems (Chapter 2). The pattern of presence and absence, resulting from spatial variation in population recovery, also afforded the opportunity to closely explore those biological processes that govern the birth and death rates of sea otters that, in turn, ultimately dictate population abundance (Chapter 6).

Entering the twenty-first century, the recovery of sea otters and the restoration of nearshore ecosystems seemed to be proceeding unimpeded throughout most of the North Pacific. However, late in the twentieth century it was discovered that across a vast portion of their northern range, most sea otter populations had collapsed (Estes et al., 1998). This turn of events provided new challenges to sea otter conservation and new opportunities to further an understanding of the functional complexity of ecosystems of which sea otters are an integral part (Chapter 4).

As a result of broad human interest in sea otters, both in terms of conservation and management, increasingly intensive research has been conducted over the last eight decades. Research questions have been diverse, embracing basic biology and life history, population biology and demography, behavior, physiology, genetics, community ecology, and interactions with marine resources such as fisheries and offshore petroleum deposits. Other lines of inquiry have included husbandry, veterinary medicine, pathology, and human-related sources of mortality. Much of the research has been focused on the recovery, conservation, and management of sea otters, while some has been directed at an improved understanding of the role of sea otters as a keystone species in nearshore ecosystems. While much of the research has been directed specifically at sea otters, many of the efforts and results are applicable to the conservation and restoration of other species and ecosystems. Perhaps one of the best examples of the concept of “keystone” predators in structuring communities and ecosystems came from research on the effects of sea otter foraging on sea urchins and the subsequent development of kelp forest communities (McLean, 1962; Estes and Palmisano, 1974).

For a variety of reasons, sea otters and their conservation have been the beneficiaries of long-term and sustained human investment rarely available to the conservation and recovery of a single species. As a consequence, an unusual level of knowledge of both basic biology and ecology exists for this species. This volume brings together many of the scientists who have been responsible for the design, implementation, and interpretation of decades of sea otter research and conservation activity. Here they share the lessons learned about sea otters that may benefit conservation and restoration of other species and systems. Contributing authors are internationally recognized experts in their fields and collectively account for many hundreds of papers in the primary scientific literature. Following a brief introduction to the life history and ecology of the sea otter, we will discuss the lessons learned from sea otter research and conservation and suggest how those lessons may be transferred to improve the conservation and restoration of degraded species and ecosystems. We also discuss persistent impediments to future conservation of sea otters and use examples from specific populations to illustrate where additional research will be of benefit. Embedded within this introduction are references to those chapters that will provide the reader with greater detail on specific topics.

Natural History

The sea otter is a member of the subfamily Lutrinae (otters) of the family Mustelidae. They are one of 13 species of otter that occur worldwide in tropical to subpolar aquatic habitats. All the otter species are recipients of protective classifications by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) or the Committee on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) (IUCN, 2013). In addition, most populations of otters receive protective classifications under local, regional, or national laws.

Contrasts between the sea otter and freshwater species of otter provide a good example of the value in understanding the underlying causes of population decline in developing conservation strategies of species in general (Estes et al., 2008). All otter species share a common relationship with humans via the intersection and shared use of preferred habitats that consist of fresh and marine waters and adjacent watersheds. Most otters occur along freshwater rivers, streams, estuaries, and lakes, where there is potential for human alteration and pollution of waterways as well as some instances of over harvesting. In the case of the sea otter, that intersection is along the continental margin and the coastal oceans of the North Pacific, another region of preferred human habitation. Perhaps a lesson to be learned from relations between all otters and humans is that habitat modification and degradation can have pervasive and long-lasting conservation consequences for many species that can be difficult to remedy. Alternatively, when habitat is relatively unchanged and ecosystems are fairly intact, as is the case for much of the sea otter’s habitat, conservation can be achieved through directed species-specific management and conservation practices.

Sea otters are a recently evolved marine mammal. Their adaptations for marine existence include relatively shallow diving capabilities and short breath hold capacities that in turn limit their foraging habitat to water depths of less than about 100 m (Berta and Morgan, 1986;...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Contributors

- Chapter Reviewers

- Preface

- Chapter 1. The Conservation of Sea Otters: A Prelude

- Chapter 2. Natural History, Ecology, and the Conservation and Management of Sea Otters

- Chapter 3. Historic and Contemporary Status of Sea Otters in the North Pacific

- Chapter 4. Challenges to Sea Otter Recovery and Conservation

- Chapter 5. Sea Otter Conservation Genetics

- Chapter 6. Evaluating the Status of Individuals and Populations: Advantages of Multiple Approaches and Time Scales

- Chapter 7. Veterinary Medicine and Sea Otter Conservation

- Chapter 8. Sea Otters in Captivity: Applications and Implications of Husbandry Development, Public Display, Scientific Research and Management, and Rescue and Rehabilitation for Sea Otter Conservation

- Chapter 9. The Value of Rescuing, Treating, and Releasing Live-Stranded Sea Otters

- Chapter 10. The Use of Quantitative Models in Sea Otter Conservation

- Chapter 11. First Nations Perspectives on Sea Otter Conservation in British Columbia and Alaska: Insights into Coupled Human–Ocean Systems

- Chapter 12. Shellfish Fishery Conflicts and Perceptions of Sea Otters in California and Alaska

- Chapter 13. Conservation in Practice

- Chapter 14. Synopsis of the History of Sea Otter Conservation in the United States

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sea Otter Conservation by Shawn Larson, James L. Bodkin, Glenn R VanBlaricom, Shawn Larson,James L. Bodkin,Glenn R VanBlaricom,Shawn E. Larson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.