- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Understanding the Rheology of Concrete

About this book

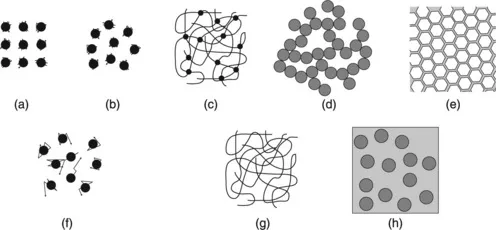

Estimating, modelling, controlling and monitoring the flow of concrete is a vital part of the construction process, as the properties of concrete before it has set can have a significant impact on performance. This book provides a detailed overview of the rheological behaviour of concrete, including measurement techniques, the impact of mix design, and casting.Part one begins with two introductory chapters dealing with the rheology and rheometry of complex fluids, followed by chapters that examine specific measurement and testing techniques for concrete. The focus of part two is the impact of mix design on the rheological behaviour of concrete, looking at additives including superplasticizers and viscosity agents. Finally, chapters in part three cover topics related to casting, such as thixotropy and formwork pressure.With its distinguished editor and expert team of contributors, Understanding the rheology of concrete is an essential reference for researchers, materials specifiers, architects and designers in any section of the construction industry that makes use of concrete, and will also benefit graduate and undergraduate students of civil engineering, materials and construction.- Provides a detailed overview of the rheological behaviour of concrete, including measurement techniques, casting and the impact of mix design- The estimating, modelling, controlling and monitoring of concrete flow is comprehensively discussed- Chapters examine specific measurement and testing techniques for concrete, the impact of mix design on the rheological behaviour of concrete, particle packaging and viscosity-enhancing admixtures

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

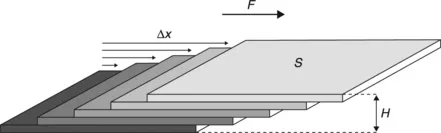

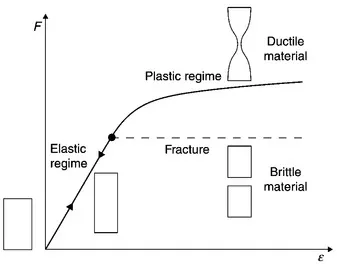

Introduction to the rheology of complex fluids

Abstract:

1.1 Solids

1.1.1 Apparent behaviour

1.1.2 Microstructural origin

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributor contact details

- introduction

- Part I: Measuring the rheological behaviour of concrete

- Part II: Mix design and the rheological behaviour of concrete

- Part III: Casting and the rheological behaviour of concrete

- Index