![]()

Connectivity of the Core Language Areas

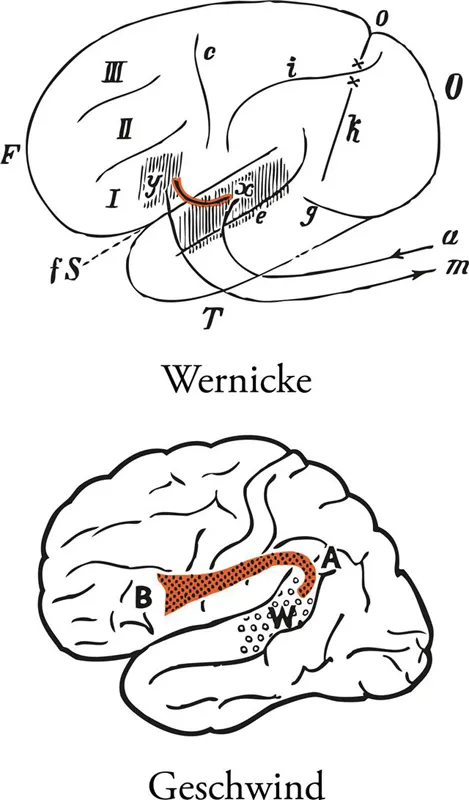

Language processing is the result of the complex functional interactions between the core language areas and other cortical and subcortical structures. The classical model of language is based on two core language regions, namely Broca's region (for language production) and Wernicke's region (for comprehension of spoken language), and the connection between them. This model was originally proposed by Wernicke (1874, 1881) in the latter part of the 19th century and was subsequently elaborated in schematic diagrams by several investigators, the so-called "diagram makers" (e.g., Lichtheim, 1885). Although speculative linkages were frequently made between these and other areas to support theoretical ideas, remarkably little anatomical data were presented or discussed to support such connections.

Wernicke depicted a direct connection between the superior temporal region and the region of the inferior frontal gyrus across the lateral fissure (Fig. 36) and speculated that this connection may be made either directly via the white matter below the insula or via an intermediate link with the insula (Wernicke, 1881). Later, however, emphasis shifted to the arcuate fasciculus as the critical link between Wernicke's region and Broca's region (Geschwind, 1970) (Fig. 36). In both cases, real anatomical data were lacking, although Wernicke attempted (but failed) to dissect a pathway under the insula. Needless to say, detailed understanding of the connectivity of the core language areas is necessary for any sophisticated theoretical modeling of their role in language processes.

FIGURE 36 Wernicke's (1881) and Geschwind's (1970) schematic diagrams illustrating the fundamental connection between the language comprehension zone in the superior temporal gyrus and the language production zone in the posterior part of the inferior frontal gyrus (Broca's region). Wernicke depicts the connection as a direct link across the lateral fissure, whereas Geschwind depicts the fundamental connection via the arcuate fasciculus, a set of fibers arching around the end of the lateral fissure. Abbreviations: a, auditory pathway; A, arcuate fasciculus; B, Broca's region; c, central sulcus; e, parallel sulcus (superior temporal sulcus); fS, fissure of Sylvius (lateral fissure); g, inferior occipital sulcus; i, intraparietal sulcus; k, anterior occipital sulcus; m, pathway to speech musculature; o, parieto-occipital fissure; x, sensory speech center; xy, association bundle between the two centers; y, motor speech center; W, Wernicke's area; I, inferior frontal gyrus; II, middle frontal gyrus; III, superior frontal gyrus. From Wernicke, C. (1881, p. 205) and Geschwind (1970), with permission. Color added to the original figures.

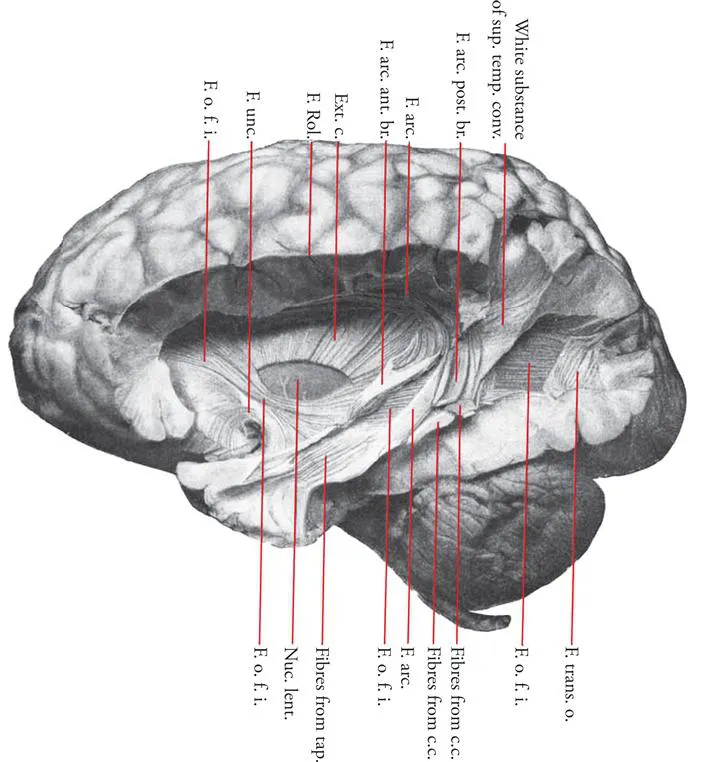

The classical method of examining the connections of cortical areas and subcortical structures has been the gross dissection of pathways in the white matter. The brain is first hardened in formalin or some other medium and the anatomist carefully dissects away the cortical grey matter before attempting to separate the white matter fascicles. This approach has provided a demonstration and definition of the classic association fiber pathways that are mentioned in standard neuro-anatomy texts: the superior longitudinal fasciculus, the arcuate fasciculus, the superior and inferior occipito-frontal fasciculi, the uncinate fasciculus, the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and the cingulate fasciculus (e.g., Curran, 1909; Klingler, 1935; Ludwig and Klingler, 1956; Klingler and Gloor, 1960; Fig. 37). The problem with this method is that while major fiber tracts running in a particular direction can be readily dissected, the precise origin and termination of the axons that form these fasciculi cannot be easily demonstrated. In other words, it is difficult to determine whether the fasciculus that has been isolated consists of monosynaptic connections (i.e. axons from area X to area Y) or whether it also includes fibers from other areas that mingle with these monosynaptic axons, but are directed to different parts of the brain.

FIGURE 37 Photograph of the gross dissection of the inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus by Curran (1909). The course of this fasciculus as viewed from the lateral aspect of the hemisphere. Abbreviations: c.c., fibers from corpus callosum mixed with arcuate fibers; Ext. c., external capsule, with part removed to show Nuc. lent., nucleus lentiformis; F.o.f.i., fasciculus occipito-frontalis inferior; F. unc., fasciculus uncinatus; F. Rol., fissure of Rolando; F. arc., fasciculus arcuatus; F. arc. ant. br., anterior branch of fasciculus arcuatus; F. trans. o., posterior part of the fasciculus transversus occipitalis, most of which has been removed to show a large window through which the inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus can be observed; tap., fibers from the tapetum perforating the corona radiata and the inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus. (Reprinted with permission of John Wiley and Sons, Curran, E. J. (1909), "A new association fiber tract in the cerebrum with remarks on the fiber tract dissection method of studying the brain", Journal of Comparitive Neurology, 19, 645–656.) Color added to the original figure.

Figure 37 illustrates the inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus, a major pathway of fibers running from the occipital region across the temporal lobe towards the frontal lobe. Although it can be readily demonstrated in gross dissections of the white matter of the temporal lobe, it is not possible to know how many of the fibers actually originate from the occipital lobe (and more specifically from which of the many visual areas within the occipital lobe) and are directed monosynaptically to the frontal lobe and how many of the fibers in the course of this fasciculus are axons from various temporal cortical areas that join those coming from the occipital cortex. Curran (1909), a master in the classical method of gross dissection who first identified this fasciculus, pointed out this problem.

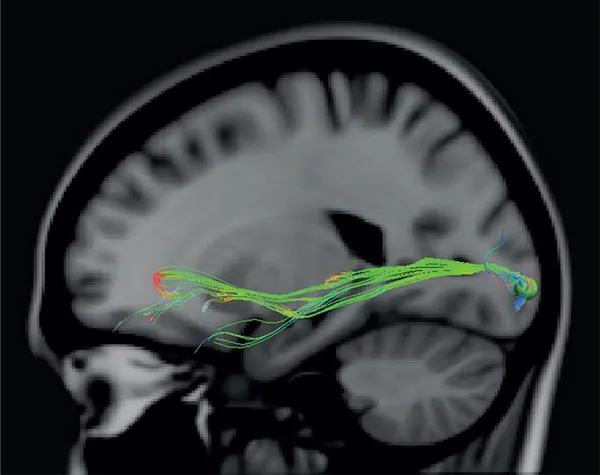

In recent years, diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), has emerged as a major method of reconstructing in vivo the axonal pathways that link different regions of the human brain. Several articles have now been published providing reconstructions of the major pathways and a number of these have focused on reconstructions of those pathways that are particularly relevant to language processing (e.g., Catani et al., 2005; Croxson et al., 2005; Makris et al., 2005, 2009; Parker et al., 2005; Anwander et al., 2007; Vernooij et al., 2007; Catani and Mesulam, 2008; Catani and Thiebaut de Schotten, 2008; Frey et al., 2008; Glasser and Rilling, 2008; Saur et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 2010). Careful examination of these reconstructions shows that, in most cases, although the core of the major fasciculi can be identified with some degree of accuracy, the precise origins and terminations of the reconstructed pathways cannot be provided (Figs. 38-40). This is due to the inherent limitations of current diffusion MRI tractography. For a review of these limitations in reconstructing the language pathways, see Campbell and Pike (2013).

FIGURE 38 Diffusion MRI reconstruction of the inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus. This fasciculus is one of the easiest fasciculi to reconstruct with modern diffusion MRI. In the current reconstruction, we placed a seed in the occipital region in one brain and the fasciculus proceeding from the occipital region across the temporal lobe towards the frontal lobe was easily reconstructed. The diffusion data were acquired with a 3T MRI scanner (Philips Gyroscan superconducting magnet system) using an A-P phase sequence. The voxel size was 2mm3 and 64 slices were acquired. The tracks were placed in MNI space by registering them to the standard ICBM 152 model with Diffusion Toolkit and TrackVis. A 4.25mm sphere was used as the region of interest seed, which can be seen in the occipital lobe.

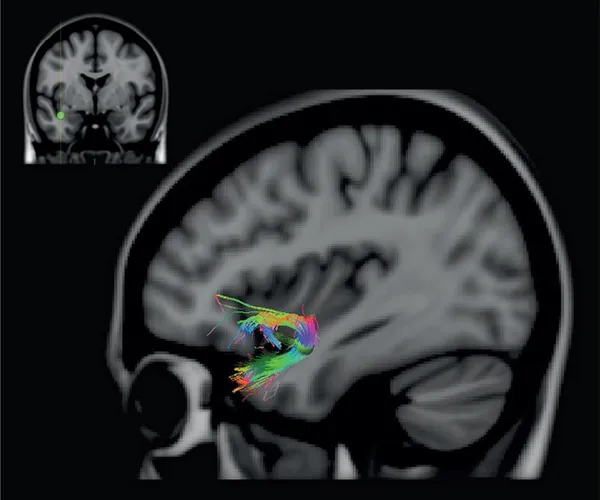

FIGURE 39 Diffusion MRI reconstruction of the uncinate fasciculus. This fasciculus links the anteriormost part of the temporal lobe with the orbital frontal region. In the current reconstruction, we placed a seed in the white matter close to the amygdala in one brain. The placement of the seed is indicated on the coronal section shown at the top left side of the figure. The sharply turning axons between the anteriormost part of the medial temporal region and the orbital/ventral frontal region can easily be visualized. It is not possible, however, to demonstrate the precise set of anterior temporal areas that project monosynaptically via this fasciculus and their exact terminations within particular orbital frontal cytoarchitectonic areas. Diffusion MRI details, as in figure 38.

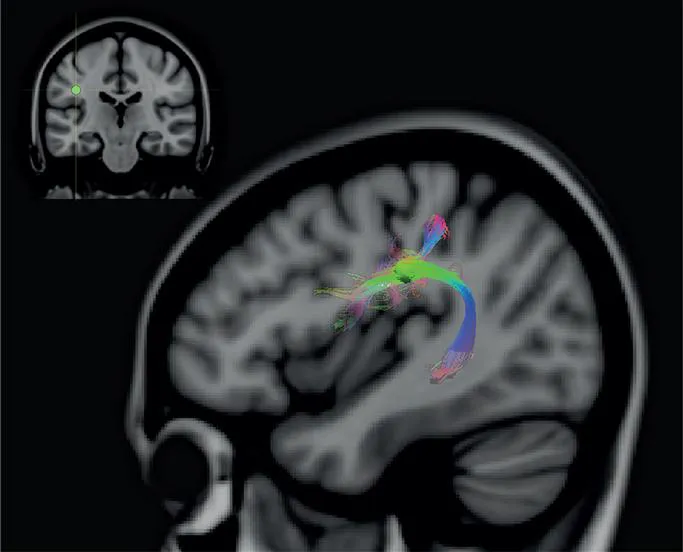

FIGURE 40 Diffusion MRI reconstruction of the arcuate fasciculus. This fasciculus, which links posterior temporal and parietal cortex below the end of the lateral fissure with lateral frontal cortex, can be easily reconstructed by placing a seed close to the end of the lateral fissure. The placement of the seed is indicated on the coronal section shown at the top left side of the figure. Diffusion MRI details, as in figure 38.

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) records the motion of water molecules in the brain and, based on this information, the microstructure of the brain tissue around which the water is moving is inferred. Although diffusion MRI tractography has become popular as a method to reconstruct pathways in the human brain and some aesthetically pleasing images have been produced, it is important to understand the current limitations of the method that can lead to major errors in the reconstruction of these pathways (see, Hagmann et al., 2006; Johansen-Berg and Behrens, 2006; Jones, 2010; Jones and Cercignani, 2010; Jbabdi and Johansen-Berg, 2011; Jones et al., 2013; Campbell and Pike, 2013). With the current methodology, false positives and false negatives abound. It is unwise, at present, for an investigator of the neural bases of language to make strong claims and base theoretical arguments on connectivity inferred from diffusion MRI data. Methodological improvements of diffusion MRI and other promising methods (e.g., Axer et al., 2011) may make it possible to reconstruct the human pathways with accuracy in the future, but this is not the case at present. The comments made above apply to its use in reconstructing the precise origin, pathway, and terminations of connections of the cortical areas of the brain. It should be noted that diffusion MRI can be very useful in clinical practice, such as in the evaluation of fiber integrity in various neurological conditions.

At this point, it becomes necessary to clarify what we mean by a "connection" between cortical areas because the term has been used ambiguously in the language literature. The cytoarchitectonically defined cortical areas are functional units of the brain that compute information and interact with specific distant corti...