Abstract:

Corrosion engineering, science and technology is the study of the interaction of materials with the environment in which they are used. Corrosion requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary outlook with core knowledge from the fields of metallurgy/materials science together with electrochemistry/surface science. Other important disciplines of relevance include: chemical engineering (particularly fluid flow), chemistry and geochemistry, conservation science, mechanical engineering and structural integrity. This chapter is intended to comprise a brief introduction to the science and technology of aqueous corrosion with an emphasis on fundamental theory. It is not intended to provide a comprehensive treatment of the subject since there are many textbooks that undertake this task to much greater depth than is possible here.

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Definition of corrosion

Corrosion is strictly the process that results in the deterioration of the performance of a material, the result of which is corrosion damage. Corrosion may be defined as: ‘a physicochemical interaction leading to a significant deterioration of the functional properties of either a material, or the environment with which it has interacted, or both of these’ [1]. It is important to note that although ‘corrosion’ is more commonly understood to involve electrochemical deterioration, such as metal dissolution, the ISO standard definition (above) also encompasses the deterioration of non-metals. The definition includes processes that involve combinations of environmental (i.e. chemical and/or electrochemical) deterioration where these are additionally influenced by applied or residual stresses in the material, and by the material microstructure as a result of manufacture or service. However, materials degradation arising from mechanisms that do not involve environmental interaction, for example mechanical overstressing, or degradation of polymers under ultraviolet radiation, fall outside this definition of corrosion.

1.1.2 Corrosion environments

Corrosion damage to materials can be caused by a wide variety of environments. More specifically it is combinations of material and environment that gives rise to corrosion damage. The most widely understood situation is for metallic (electrochemical) corrosion in aqueous (i.e. water-containing) environments with or without dissolved species such as electrolytes (i.e. salts) and reactants (e.g. dissolved oxygen). However, corrosion damage also results from other material–environment combinations; e.g. solvent cracking of polymeric materials, ‘bleeding’ corrosion of aluminium in chlorinated hydrocarbons and sulphate attack on cementitious materials such as concrete. Corrosion damage also results from exposure of materials to gaseous atmospheres, such as air, steam, etc. (e.g. high-temperature corrosion).

1.1.3 Examples of corrosion damage

General or uniform corrosion, where active metal dissolution is the dominant corrosion mechanism, is not normally of great significance in nuclear plant as corrosion-resistant (passive) alloys (e.g. stainless steels, nickel alloys, zirconium fuel cladding) are the workhorse materials in use. However, general corrosion may also be of significance in the civil engineering structures associated with the nuclear site. Importantly, general corrosion is the main controlling mechanism for certain materials used in nuclear waste containment (e.g. copper, carbon steels, cast iron, etc.).

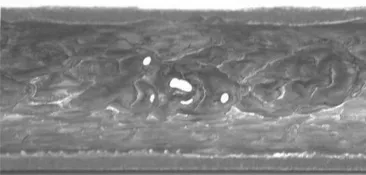

Localised forms of corrosion (i.e. pitting, intergranular attack, stress corrosion cracking or corrosion fatigue) are generally more important and are often critical to reactor plant performance and lifetime. Similarly the lifetime of nuclear waste containers manufactured from corrosion-resistant alloys is dependent upon localised corrosion damage (Fig. 1.1). As another example, corrosion processes that are associated with flow of fluids within the plant can give rise to flow-assisted corrosion (Fig. 1.2).

1.1 Surface stress corrosion cracks initiating from a pit in 316L stainless steel exposed to a MgCl2 salt deposit at a relative humidity of 30% and at a temperature of 40°C.

1.2 Flow-assisted corrosion (erosion-corrosion) on seawater-cooled copper condenser tubing from 500 MW coal-fired station.

1.1.4 Economics of corrosion

Although difficult to quantify, the cost of corrosion in developed economies is often estimated to be in the range of 2–4% of gross national product per annum [2]. Generally the costs of material, manufacture, installation and commissioning, etc., are included in this amount. However, it is often the costs of service failures (i.e. repairs and especially lost production) that are the most significant and the most difficult to quantify. For existing nuclear plant, the safety cases for life extension are often predicated on continuing good corrosion performance of the service components, including the reactor pressure vessel. For new build plant, the challenges of achieving a 60-year lifespan are formidable, and understanding the key corrosion mechanisms (and how to control or limit corrosion damage) is critical to developing reliable systems [3].

1.2 Fundamentals of aqueous metallic corrosion

1.2.1 Electrochemistry

The overall corrosion process necessarily involves at least two simultaneous reactions: an oxidation (or anodic) reaction and a reduction (or cathodic reaction), which are coupled through the exchange of electrons and are therefore known as electrochemical reactions. Examples of anodic (oxidation, electron-donating) reactions include:

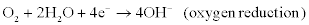

Examples of cathodic (reduction, electron-accepting) reactions include:

A corrosion cell, therefore, necessarily contains an anode, a cathode and an electrolyte (i.e. a medium through which the ionic species involved in the anodic and cathodic reactions are transported). For aqueous corrosion the electrolyte also contains the corrosive medium or agents and contains dissolved products of corrosion (e.g. ions, colloids and neutral species).

It is important to appreciate that a corrosion cell involves two simultaneous reactions (anodic and cathodic) that must proceed at the same time and the same rate, but not in the same place. Thus, anodes and cathodes are necessarily spatially separated.

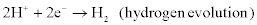

1.2.2 Anode and cathode separation

During corrosion, the local electrochemical potential (or voltage) at an anode is different from that at a cathode. Also, the local electrochemical reactions at anodes and cathodes result in significant chemical changes in their vicinity that encourage and maintain their spatial separation. Furthermore, this potential difference in solution gives rise to a voltage gradient, which attracts oppositely charged ions (or repels similarly charged ions), a process known as electro-migration. Additionally, the requirement for electro-neutrality in the electrolyte (by which is meant that an anion cannot exist in solution without a corresponding cation) gives rise to diffusion in the electrolyte. The overall process for corrosion of iron, with oxygen as the cathodic reactant, is shown schematically in Fig. 1.3, with migration and diffusion of ions carrying the flow of current.

1.3 Schematic diagram showing spatial separation of anode from cathode with corresponding migration of ions in solution.

It is important to note that corrosion damage (e.g. metal loss) generally occurs at the anodic locations while at the cathodic locations no corrosion damage occurs. For alloys subject to general corrosion, the locations of anodes and cathodes tend to move randomly over the surface of the metal and, on average, metal thinning occurs relatively uniformly. However, for corrosion resistant alloys, which are covered by a passive oxide film, the location of an anode tends to become strongly localised thus giving rise to localised corrosion damage, e.g. pitting corrosion, crevice corrosion and stress corrosion cracking.

1.2.3 Electrochemical thermodynamics

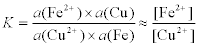

The controlling thermodynamic equation for an electrochemical process is the Nernst equation that relates the equilibrium constant, K, for a reaction:

where the mathematical operator symbol Π means ‘the product of’, and a(x) means ‘the thermodynamic activity of species x’. Thus, for the copper plating (displacement) reaction on iron:

By convention, the activity of a pure substance in its standard state (i.e. pure copper, Cu, and iron, Fe) is equal to 1; also, the activity of a substance is approximately equal to its concentration, except ...