- 356 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A History of Modern Immunology: A Path Toward Understanding describes, analyzes, and conceptualizes several seminal events and discoveries in immunology in the last third of the 20th century, the era when most questions about the biology of the immune system were raised and also found their answers. Written by an eyewitness to this history, the book gives insight into personal aspects of the important figures in the discipline, and its data driven emphasis on understanding will benefit both young and experienced scientists.

This book provides a concise introduction to topics including immunological specificity, antibody diversity, monoclonal antibodies, major histocompatibility complex, antigen presentation, T cell biology, immunological tolerance, and autoimmune disease. This broad background of the discipline of immunology is a valuable companion for students of immunology, research and clinical immunologists, and research managers in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

- Contains the history of major breakthroughs in immunology featured with authenticity and insider details

- Gives an insight into personal aspects of the players in the history of immunology

- Enables the reader to recognize and select data of heuristic value which elucidate important facets of the immune system

- Provides good examples and guidelines for the recognition and selection of what is important for the exploration of the immune system

- Gives clear separation of descriptive and interpretive parts, allowing the reader to distinguish between facts and analysis provided by the author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Modern Immunology by Zoltan A. Nagy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Immunology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Pre-history with Far-reaching Consequences

Outline

Chapter 1 The Immunological Revolution

Chapter 1

The Immunological Revolution

Abstract

It was the period from about 1950 to 1970 when the fundaments of modern immunobiology were laid down. The discovery that humoral and cellular immune reactions are mediated by two distinct lymphocyte lineages, B cells and T cells, has revolutionized immunological thinking. The structure of immunoglobulins and the molecular basis for hypersensitivity reactions were also discovered in this period. The conceptual highlight of this era was the clonal selection theory that, for the first time, correctly accounted for the origin, development, and specificity of immune reactions.

Keywords

B cell; clonal selection; constant (C) region; IgA; IgD; IgE; IgG; IgM; immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy (H) chain; light (L) chain; T cell; variable (V) region

Those who received their biomedical education around 1960 could not even have suspected that one of the most significant revolutions in life-sciences was taking place at that time: the transformation of serology-centered immunology into immunobiology. Students could not have possibly been informed about this, as the university textbooks at that time were only allowed to contain solid, well-established facts of science, notably those that had survived at least a decade without being refuted. Thus little wonder that the students missed out the birth of immunobiology. As a matter of fact, immunology at that time was not considered as a science in its own right, it usually occupied a single chapter in the students’ microbiology textbook, describing at most vaccination, antibodies, serological reactions, and the use of antibodies for typing of bacteria. The most sophisticated piece of science included was the description of how to render antisera ‘monospecific’ by sequential absorption. Concerning the possible nature and origin of antibodies, a single laconic statement was made, namely that they were localized in the gamma-globulin fraction of serum, implying cautiously that not all gamma-globulins were necessarily antibodies. Indeed, the bulk of gamma-globulins was thought to represent ‘normal’ serum proteins that were probably produced in the liver (by the motto that substances of unknown nature and origin are best to be blamed on the liver; nota bene, even old, conservative textbooks could contain not all that solid facts!). Naturally, nothing about the cellular basis of immunity passed the inclusion criteria, since the first discoveries in this direction were at most a couple of years old. It is not surprising that the biologically interested student, after reading through the chapter, might have concluded: ‘All this may well be very useful, but rather boring.’

Consequently, chances were meagre that creative students would have decided to join immunology research, the few exceptions were those who attained the new knowledge by self-education.

At this point, the reader may wonder why self-evident questions, such as the cellular origin of immunity, were not addressed long before 1960. The explanation lies in what one could rightly call a historical artefact. Namely, immunology in the preceding 50 years had dealt only with antibodies, and immunologists had been convinced that clarifying the nature of antibodies and of their interaction with antigen would answer all outstanding scientific questions. In accordance with this notion, the approach to immunology was predominantly chemical, biological concepts hardly having a chance to penetrate the field. Therefore, the designation of this era by historians as the ‘dark ages of immunology’1 is not quite unfounded, although important contributions were also made at this time, in particular to serology. The prevailing paradigm blindfolded immunologists so strongly that new facts, not accounted for by the effect of antibodies, were needed to change their mind.

The earliest ‘heretical’ phenomenon was delayed-type (or tuberculin-type) hypersensitivity (DTH; its history is amply described1). It had been known for some 50 years that Mycobacterum tuberculosis, when administered intradermally in small amounts, caused a local inflammatory reaction, which was also widely used as a reliable diagnostic marker for previous infection. Although it was noted that the reaction developed in the absence of circulating antibodies against the bacteria, it was easier to ‘sweep it under the carpet’ by postulating that it represented a local, non-immunological reaction against toxic bacterial products. But this proposition became untenable some 20–30 years later, when it was demonstrated that DTH could also be induced with a variety of simple proteins. Soon became the immunological nature of the reaction also evident, and the finding that it could be passively transferred with blood cells of sensitized donors to naïve recipients2 marked the birth of cellular immunology.

Studies on the mechanism of skin-graft rejection were even more revealing. Thanks mostly to Peter Medawar and his group, the immunological nature of graft rejection was proven quickly and beyond any doubt,3,4 and it was also observed that the majority of cells infiltrating the graft were lymphocytes, providing the first hint to an immunological role for this abundant but thus far functionless blood cell population. Further, it was shown that graft rejection was not accompanied by antibody formation against donor erythrocytes, and that the immunizing antigens were on donor leukocytes.5 Finally, the demonstration by Mitchison6 and Billingham et al.7 that transplantation immunity could be adoptively transferred with cells but not with the serum of sensitized donors placed graft rejection into the category of cellular immunity together with DTH. Thus, here were two, well-established immunological phenomena that had nothing to do with antibodies.

A major eye-opener was also the discovery of immunological tolerance8,9 that could not be explained by the then-fashionable instructive models of antibody production (the latter proposed that antigen would instruct, or even serve as a template for antibody synthesis). Finally, the accumulation of new evidence alerted immunologists to wake up from their ‘sleeping beauty slumber’, and start asking all those questions that would have been due long ago. These were the most important preparatory steps to what is usually referred to as ‘the immunological revolution’.

1.1 The Clonal Selection Theory

If immunologists were asked to name one single event that marks the beginning of the immunological revolution, most of us would vote for the appearance of ‘The Clonal Selection Theory of Acquired Immunity’10 by Macfarlane Burnet in 1959. This theory provided, for the first time, a biology-based conceptual framework for the development of immune responses, and its main theses have remained valid to date, so it has rightly become the alphabet of immunological thinking, and it is now ‘in the blood’ of every immunologist.

Of course, the clonal selection theory did not come ‘out of the blue’, it was indeed preceded by two major selectional hypotheses, namely the side-chain theory11,12 of Paul Ehrlich in 1897, and the natural selection theory13 by Niels Jerne in 1955 (the gap in between was filled with instructional theories of the ‘dark ages’). Common to all three concepts is the basic postulate that antibodies are natural components of the body, produced at a slow, constant rate, independent of antigen challenge (a sharp demarcation from the instructionists’ view). The role of antigen is then to select and bind to the appropriate specific antibody (out of a mixture of many), and this triggers the production of large amounts of the same antibody. The distinctive features of the three theories lie in the assumed place of selection and the subsequent events.

Ehrlich placed the antibodies as ‘side-chains’ onto the surface of cells. In his view, a single cell possesses many different side-chains, but only those binding antigen will be overproduced and shed into the blood. In contrast, Jerne’s natural antibodies were assumed to circulate in the blood, and the ones binding antigen would then be transported to specialized cells capable of producing the very same antibody. How this transport and the subsequent triggering of specific antibody production would occur have remained unexplained.

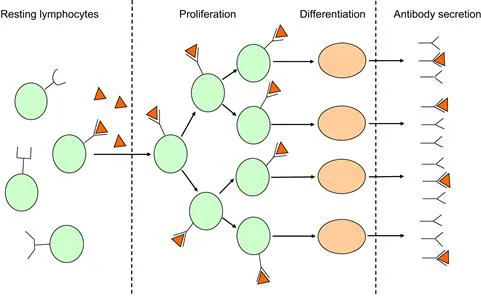

Burnet’s concept that also incorporated new knowledge about protein synthesis was the one to hit the nail on the head. Burnet realized that neither antigen nor antibody could carry specific information to a cell to induce antibody formation, what they could do at most is to signal a pre-programmed machinery for protein synthesis. Thus he placed the natural antibody of Jerne back onto the cell surface as a receptor, similarly to Ehrlich. And here came the stroke of genius: he postulated that each specific antibody receptor was only expressed on a single cell and its descendants, i.e., a cell clone. This statement implied that cells of each clone had been programmed to produce one single antibody specificity. Specific binding of antigen would trigger only the cells of the relevant clone to expand (proliferate) and differentiate into antibody-secreting cells (Fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Schematic representation of Burnet’s clonal selection theory. Resting lymphocyte clones (circles) express different receptors. Antigen (triangles) finds a clone with the appropriate receptor. The selected clone proliferates, differentiates into plasma cells (ellipses) and the latter secrete antibody of the same specificity. Based on Reference 1.

Besides being essentially correct, Burnet’s theory offers several advantages. First, it allows the body to run several different immune responses simultaneously, a definitive advantage in a pathogen-ridden world. Furthermore, the postulated clonal expansion accounts nicely for the observed continued antibody production after elimination of the antigen, as well as for the enhanced antibody response upon repeated immunization (‘booster effect’). To explain the improved quality of antibodies after booster (‘affinity maturation’), Burnet invoked minor somatic mutations in the antibody-encoding gene, an aspect that was further elaborated by Lederberg.14 The newly discovered phenomenon of self-tolerance could also be explained by the deletion of self-reactive clones early in ontogeny.

From the experimentalists’ point of view, the most attractive aspect of the theory was that many of its postulates were testable. For example, with the development of the new immunofluorescence technique, it became easy to demonstrate that the precursors of antibody-forming cells (now B cells) indeed carried immunoglobulin receptors on their surface. Indirect evidence also accumulated to support the one-cell-one-antibody thesis. First, each B cell was shown to express antibodies of a single molecular species, i.e., the same heavy and light chain class of immunoglobulin, and in animals heterozygous for immunoglobulin allotypes (allelic variants of immunoglobulin) either one or the other allotype but not both.15 The latter finding has indicated that mechanisms must exist in the lymphocyte that inactivate the immunoglobulin gene in one of the two parental chromosomes (‘allelic exclusion’), pointing again in the direction of lymphocyte monospecificity. Second, using radiolabeled antigens, specific antigen binding was demonstrated to only very small fractions of lymphocytes,16 suggesting clonality of their antigen receptors. Third, the use of heavily radioactive antigens permitted selective killing of antigen-binding cells by local radiation, and the remaining cell population was shown to be incapable of responding to the same antigen, whereas it responded to other antigens normally.17 The latter, so called ‘antigen-suicide’ experiments provided the strongest indirect evidence for the clonality of immune response. But the final evidence came from the discovery of monoclonal antibodies,18 whose very existence would be impossible, if lymphocytes were not monospecific. The proposal that clonal deletion should be a mechanism of immunological tolerance was also proven experimentally, some 30 years later.19–21

Besides his theoretical contribu...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Introductory Words About Science, Scientists, and Immunology

- Part I: Pre-history with Far-reaching Consequences

- Part II: The History

- Concluding Remarks

- Index