1 Introduction

Experimental psychologists may appear strange when compared to the specialists working in most of the other experimental sciences. While in physics, chemistry, molecular biology, and virtually all other scientific disciplines professionals use methods of research that they know scrupulously in terms of their nature and fundamentals—especially on how the effects of a manipulation are brought about—in psychology a method is sometimes used even when there is no precise understanding. A characteristic example is the method of visual masking. Masking can be defined as impaired perception of a target stimulus as a result of presenting another, masking, stimulus close in time and space to a target (Breitmeyer & Öğmen, 2000; Kahneman, 1968). When sensation, perception, sensory memory, attention, visual cognition, and/or affective effects of stimulation are studied it is important to exert precise control over the duration a stimulus is presented and keep the value of this parameter invariant when independent variables of this domain are meant to remain invariant. Often it is also necessary to limit the effect of a stimulus so that it remains less than optimal or even restrict its effect so that subjects do not perceive the stimulus consciously. In both these cases visual masking is used as a standard experimental tool to control and limit the time the stimulus and perhaps its effects are present. However, these uses of masking to some extent trade one unknown for another. Visual masking itself as a mental (sensory, perceptual, cognitive, and neurobiological) phenomenon is not very well understood. By an analogy, the situation is similar to when someone switches off electricity from a corporate building knowing that soon there will be a serious perturbation in work output and social interaction but without knowing precisely how, why, and when specific processes will be disturbed, ended, and/or prolonged. This means that research using masking as a tool may be prone to unaccounted experimental confounds, misinterpretations, imprecision, and artefacts.

Therefore, knowledge of the nature and of the underlying mechanisms of visual masking has a much broader implication for quality psychological research than simply a curiosity to better know the phenomenon itself. On the other hand, because visual masking as a phenomenon stands at the crossroads between a multitude of timely research topics such as preconscious versus conscious processing, effects of priming, neural correlates of consciousness (NCC), timing of mental responses, comparative effects of sensitivity and bias, Bayesian approaches to cognition, relative effects of sensory and memory factors on performance, and feedforward versus reentrant processing, progress in uncovering the mechanisms of masking would also mean progress in many other areas.

Since the last published reviews on masking (Ansorge, Francis, Herzog, & Öğmen, 2007; Bachmann, 1994; Breitmeyer, 1984; Breitmeyer & Öğmen, 2000, 2006; Enns & Di Lollo, 1997, 2000; Felsten & Wasserman, 1980; Francis, 2000, 2006; Ganz, 1975; Kahneman, 1968; Kouider & Dehaene, 2007; Raab, 1963; Turvey, 1973) some notable additions and advances have appeared in masking research, which this book is set to review. As the comprehensive text on masking by Breitmeyer and Öğmen was published in 2006 we present our work on research published afterward. The need for this kind of a book stems also from the difficulty that an unexperienced reader (both junior scientists and established researchers not well versed in masking) might have to obtain sufficient knowledge in this domain, because masking research is dispersed over diverse, numerous, and often mutually isolated sources. As mentioned in the outset, masking continues to be one of the central experimental techniques in research on consciousness, priming, and implicit processes leading to cognitive control and servicing executive functions. At the same time some misinterpretations of masking effects and careless practices in the use of masking as a method, persist. This opinion is based on our extensive reading of the masking literature in particular and cognitive literature in general.

The aims of this work are: (i) helping the interested reader—and there are many because masking is among the central experimental tools—to get succinct information about the widely dispersed masking studies; (ii) point out some new trends in masking research; (iii) add the effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) as a new method to the traditional psychophysical masking methods and present a review of this new trend; (iv) comment on the methodological pitfalls hidden in the practice of masking thus helping to improve the quality of future research where masking is used as a tool; and (v) inform readers about recent developments in theoretical attempts to understand masking. The key messages are that masking continues to be a valuable tool (i) for studying the temporally unfolding NCC, (ii) for research on objective versus subjective measures of perception, (iii) for the measurement and analysis of the different stages of perception and cognition so as to arrive at more valid models of visual information processing. No less importantly, (iv) one becomes aware of the commonly encountered counterproductive and misleading practices and perhaps premature interpretations when using masking or specifically studying it.

Our text is organized as follows. We begin by briefly describing the basic concepts and categories of visual masking. We then discuss the following topics: individual differences in masking effects, sensitivity, bias and criterion contents in masking, masking and attention, masking and consciousness, dependence of masking on the characteristics of target and mask stimuli and effects on mask perception, microgenesis and masking, new forms of masking, masking by TMS, modeling masking, applied aspects of psychobiology and the psychophysics of masking.

2 The Concept of Masking, Varieties of Masking, and Main Theories of Masking

Masking as a phenomenon and as a method for research has been known for around a century (Baade, 1917; Baxt, 1871; Piéron, 1925a, 1925b, 1935; Stigler, 1910; see Breitmeyer, 1984 and Bachmann, 1994 for reviews). However, the intensive study of sensation, perception, and attention, aided with the method of masking, began after the Second World War, with an especially intense period of research between the 1960s and 1980s (see Bachmann, 1994 and Breitmeyer & Öğmen, 2006 for reviews). After a relatively quieter interim time, activity in masking research was revitalized with the arrival of more widespread use of new brain imaging technologies and with the emergence of scientific studies of consciousness at the turn of the millennium.

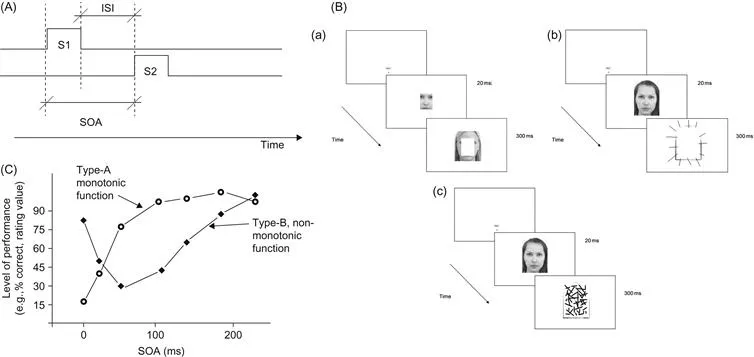

There are several quite different phenomena subsumed under the umbrella of the term “masking.” Most often masking research uses very brief target stimuli accompanied in time and space by the typically brief or a bit more extended masking stimuli, with time intervals separating the target and the mask onsets (stimulus onset asynchrony, SOA) being very short—in the neighborhood of 0–200 ms. When timing of the interval between the termination of one of the stimuli and the start of the other of the stimuli is used as a temporal parameter, it is called the interstimulus interval (ISI). In most cases, SOA has more predictive power with regard to the effects of masking than ISI (Bachmann, 1994; Breitmeyer & Öğmen, 2006; Turvey, 1973, but see Francis, Rothmayer, & Hermens, 2004). The masking stimulus (mask) is presented before the target in forward masking, after the target in backward masking, and during the target in simultaneous masking. Typically, backward masking is stronger than forward masking. According to the spatial layout properties of the mask, masking is classified as masking by light (a homogenous flash), masking by noise, masking by pattern, masking by object, or metacontrast/paracontrast masking. Whereas for the previous cases the mask usually spatially overlaps with the target position, metacontrast is a variety of backward masking where the target and mask images do not overlap in space but are closely adjacent in space (Werner, 1935). Paracontrast refers to forward masking by a spatially nonoverlapping, adjacent mask. The typical way to express the effect of masking is to plot target visibility (e.g., apparent contrast, detectability, level of correct discrimination or recognition, subjective clarity) as a function of SOA or ISI. Sometimes the values of luminance/contrast threshold as a function of SOA (ISI) are also used. (See Figure 1.1 for target-mask sequence types, examples of masks, and types of masking functions).

Figure 1.1 (A) Illustration of how ISI and SOA are specified according to the temporal order of the first presented stimulus (S1) and second presented stimulus (S2). When S1 is target and S2 is mask, masking is called backward masking; in case of the reverse order of target and mask there is forward masking. (B) (a) an example of metacontrast masking with short-duration target and long-duration mask; (b) an example of luminance-masking with short-duration target and long-duration mask; (c) an example of pattern masking with short-duration target and long-duration mask. In masking research, targets and masks of comparable durations are also often used. (C) Common types of masking functions—type-A monotonic and type-B nonmonotonic masking specified as level of performance (percent correct detection or identification, value of psychophysical rating of clarity or confidence, etc.) as a function of SOA.

If a backward mask does not cover the target in space and is spatially and form-wise sparse (e.g., four dots surrounding a target image such as a Landolt C), the masking effect is absent. However, when the same target and mask are presented among the spatially distributed distractor objects (with the subject not knowing beforehand where the target is located), with the mask specifying which object is the target and when mask offset is delayed considerably after target offset (a simultaneous onset, asynchronous offset display), strong masking occurs (Di Lollo, Enns, & Rensink, 2000; Enns & Di Lollo, 1997). This variety of masking is called object substitution masking (OSM). In these situations traditionally weak masks have strong effects when attention is not focused on the target before its presentation.

Habitually and stemming from the typical experimental results, masking functions overwhelmingly show up in two types—type-A, monotonic masking where target perception improves monotonically with increases in SOA and type-B, nonmonotonic (U- or J-shaped) masking where optimal SOAs leading to strongest masking cover an intermediate positive target-mask temporal separation (Bachmann, 1994; Breitmeyer, 1984; Kahneman, 1968). Type-B masking occurs more often with metacontrast than noise/light masking and when energy (duration and/or luminance) or contrast of the first presented stimulus is higher than that of the following stimulus or at least equal to it. When targets are very brief and masks have a long duration, type-A masking tends to prevail.

In psychophysical studies target- and masking stimuli are sometimes presented for longer durations over hundreds or thousands of milliseconds and in that case they are simultaneous or semisimultaneous. Also, long masks and brief targets may be used. The dependent measures are typically contrast, luminance, duration, or dynamic transformation thresholds of visibility. A popular type of stimulus in these types of masking studies consists in spatial periodic modulation of contrast (e.g., gratings, Gabor patches, and textures). We do not review this variety of masking here (for reviews and examples see Bex, Solomon, & Dakin, 2009; Hansen & Hess, 2012; Huang, Maehara, May, & Hess, 2012; Klein & Levi, 2009; Legge, 1979; Legge & Foley, 1980; Meese, Challinor, & Summers, 2008; Serrano-Pedraza, Sierra-Vázquez, & Derrington, 2013; Stromeyer & Julesz, 1972; Wallis, Baker, Meese, & Georgeson, 2013). The concept of camouflage is also related to our topic, but we also omit this aspect of masking from our review. (For an example of a camouflage-masking study see Wardle, Cass, Brooks, & Alais, 2010).

It is possible to obtain masking effects by combining the brief transient presentations of targets and masking stimuli in such a way that a longer temporal sequence—a stream—is formed. The paradigms of rapid serial visual presentation as used in the attentional blink and repetition blindness studies belong to this variety (Dux & Marois, 2009; Martens & Wyble, ...