1.1 Bitumen

British Standard 3690, Part 1: 1989 defines bitumen as ‘A viscous liquid, or solid, consisting essentially of hydrocarbons and their derivatives, which is soluble in trichloroethylene and is substantially non-volatile and softens gradually when heated. It is black or brown in colour and possesses waterproofing and adhesive properties. It is obtained by refinery processes from petroleum, and is also found as a natural deposit or as a component of naturally occurring asphalt, in which it is associated with mineral matter’.

Man has made use of bitumen and bituminous binders for thousands of years. There are many references to bitumen in the Bible. In Genesis it refers to Noah’s waterproofing of the ark which was ‘pitched within and without with pitch’. Pitch is the Latin equivalent of ‘gwitu-men’ which was subsequently shortened to ‘bitumen’, then passing via French into English. Also, in the description of the building of the Tower of Babel, ‘they used bricks for stone and bitumen for mortar’ (Whiteoak, 1990). For over 5000 years bitumen has been used as a waterproofing and/or bonding agent (Abraham, 1945). The earliest recorded use was by the Sumerians around 3800 BC and the Egyptians used it in their mummification processes (Volke, 1993; Chirife et al., 1991).

Bitumen occurs naturally, as mentioned above, and also remains after crude oil has been refined. Since the turn of the twentieth century demand for bitumen has far outweighed that available from naturally occurring sources. ‘Natural’ bitumen is found in the vicinity of subterranean crude oil deposits where surface seepages may occur at geological faults. The amount and nature of this naturally occurring material depend on a number of natural processes which modify the properties of this material. This product is often accompanied by mineral matter, the amount and nature of which depend on the circumstances which caused such an admixture to occur (Whiteoak, 1990).

Crude oil originates from the remains of marine organisms and vegetable matter deposited with mud and fragments of rock on the ocean bed. Over millions of years organic matter and mud accumulate into layers hundreds of metres thick, the immense weight of the upper layers compressing the lower layers into sedimentary rock. Conversion of organisms and vegetable matter into hydrocarbons of crude oil is thought to be the result of the effect of heat from the earth’s crust and of pressure applied by the upper sedimentary layers, possibly aided by the effects of bacterial action and radioactive bombardment. As further layers of sediment were deposited on the sedimentary rock where the oil had formed, the additional pressure squeezed the oil sideways and upwards through porous rock. Porous rock extends to the earth’s surface, allowing oil to seep through, resulting in surface seepages (Whiteoak, 1990).

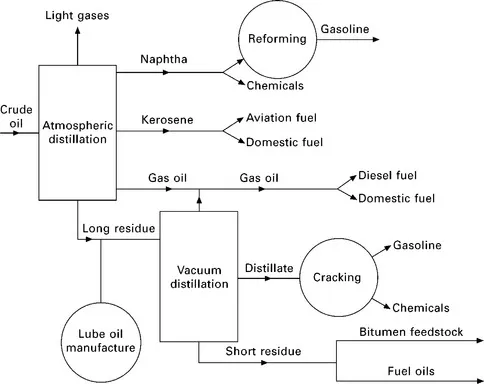

In general, there are four main oil producing regions in the world: the USA, Russia, the Middle East and the countries around the Caribbean. Bitumen is obtained by the fractional distillation of the crude oil at 300–350°C. Figure 1.1 shows a schematic diagram of the distillation process.

1.1 Schematic diagram of the fractional distillation of crude oil to yield bitumen feedstock. (Whiteoak, 1990)

The lighter fractions (e.g. propane and butane) come off first, followed by naphtha, kerosene and gas oil, distillates and short residue. It is this short residue which is the feedstock used in the manufacture of many different grades of bitumen. Oxygen is blown through the short residue and, depending on the temperatures and pressures used, and how much oxygen is added, different grades of bitumen are obtained. In the UK bitumen is generally classified into four grades:

1. Penetration grades: specified by penetration (British Standard 2000, Part 49: 1983) and softening point (British Standard 2000, Part 58: 1983), tests.

2. Cutback grades (to which kerosene has been added): specified by viscosity.

3. Hard grades: specified by penetration test and softening point range.

4. Oxidised grades: specified by penetration and softening point tests and also by solubility criteria.

Bitumen is considered to be a complex mixture of high molecular weight hydrocarbons and non-hydrocarbons which can be separated into fractions consisting of asphaltenes, resins, aromatics and paraffins (Traxler, 1936). Three types of hydrocarbons are present in bitumen; paraffinic, naphthenic and aromatic. Non-hydrocarbons in bitumen have heterocyclic atoms consisting of sulphur, nitrogen and oxygen. Elemental analysis of bitumen manufactured from a variety of crude oils shows that most bitumens contain:

• Carbon 82–85%

• Hydrogen 8–11%

• Sulphur 0–6%

• Oxygen 0–1.5%

• Nitrogen 0–1%.

Trace quantities of metals such as nickel, iron, vanadium, calcium, magnesium and chromium are also found in bitumen (Atherton et al., 1987).

Chemically, asphaltenes are multilayer systems containing a great variety of building blocks. Initially, Nellensteyn in 1933 proposed that asphaltenes contained a microcrystalline graphitic-type nucleus (Nellensteyn, 1933), but in 1940 Pfeiffer and Saal suggested that asphaltenes were high molecular weight hydrocarbons of an aromatic character (Pfeiffer and Saal, 1940). Exhaustive studies by Yen and co-workers (Yen et al., 1961, 1962; Yen and Erdman, 1962, 1963; Yen and Dickie, 1968), Strausz and co-workers (Ignasiak et al., 1977; Rubenstein and Strausz, 1979; Payzant et al., 1979, 1992; Rubenstein et al., 1979) and others have identified many different chemical structures in asphaltenes. The average asphaltene molecule contains a flat sheet of condensed aromatic systems which may be interconnected by sulphur, ether, aliphatic chains or naphthenic ring linkages. Gaps and holes in th...