![]()

Chapter 1

Thermodynamics of (Nano)interfaces

Paolo Bergese*; Italo Colombo† * Laboratorio di Chimica per le Tecnologie, Dipartimento di Ingegneria Meccanica e Industriale, Università degli Studi di Brescia, Via Branze 38, 25123 Brescia, Italy

† Physical Pharmacy Laboratory, Pharmaceutical Development Department, Aptalis Pharma S.r.l., Via Martin Luther King 13, 20060 Pessano con Bornago (Milan), Italy

Abstract

This chapter is a tutorial to the description of nanosystems by classical interfacial thermodynamics. After synthetically recalling the necessary basics, it shows by working examples of increasing complexity that several properties of inorganic, biological, and hybrid nano-objects are not stand-alone weird subjects but rather aspects of colloid and interface energetics. Touched topics include melting temperature and solubility of nanocrystals, superhydrophobic surfaces, and biomolecular machines.

Keywords

thermodynamics

nanocrystals

superhydrophobicity

molecular machines

nanomechanics

One of the principal objects of research in any department of knowledge is to find the point of view from which the subject appears in the greatest simplicity.

Josiah Willard Gibbs [1]

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Stefania Federici for helpful discussion and Figure 1.5. This chapter has been realized as part of the divulgation activities of the project Nanostructured Soft Matter: from Fundamental Research to Novel Applications (PRIN 2010-2011, Grant No. 2010BJ23MN).

1 Classical Nanothermodynamics

The mission of this chapter will be to show that some vintage thermodynamics of colloids and interfaces may offer a simple and effective route toward a general understanding of several fundamental nanoscience topics, from size dependence of melting temperature in nanocrystals to nanomechanics of protein thin-film machines.

Thermodynamics is concerned with concepts and laws to describe the forms and transformations of energy. Classical thermodynamics, the forefather of the family, fully matured during the nineteenth century to describe macroscopic systems (delimited portions of the observable world) in equilibrium or undergoing reversible processes such as exchange of heat, work, and matter with the surroundings (the rest of the observable world). Classical thermodynamics can be considered one of the outstanding achievements of the human mind and favorably compared with the harmonious and self-consistent structures of Euclidian geometry and analytical mechanics [2]. In addition, it has the peculiarity to stand aloof from any microscopic model of the system but at the same time to provide arguments and quantitative information useful to frame it.

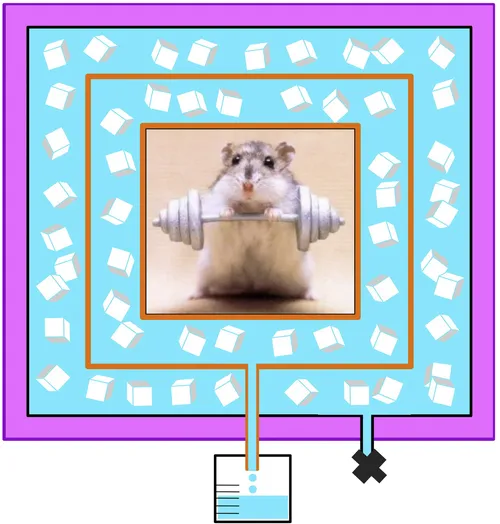

A striking example of this unique feature—which makes classical thermodynamics a very powerful intellectual tool to grasp complex systems—dates back to 1780. At that time, far before biochemistry and molecular biology were invented, Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace realized the world's first ice calorimeter and used it to estimate the energy involved in guinea pig metabolism [3]. A scheme of their ice calorimeter is reported in Figure 1.1. It is made of three concentric chambers: The inner chamber hosts the guinea pig, which passes the heat he releases to the intermediate chamber filled with ice and water. The outside chamber is also packed with ice and water (snow, in the original setup) in order to grant that the only heat received by the intermediate chamber comes from the inner chamber. In this configuration, the heat produced by the guinea pig metabolism upon respiration can be determined after weighting the mass of water that elutes from the intermediate chamber (provided the specific latent heat of melting of water is known). The experiment allowed Lavoisier to conclude: “La respiration est donc une combustion.”

Figure 1.1 Measuring guinea pig metabolism by an ice calorimeter.

One of the most popular properties of nanomaterials is the astonishing surface-to-mass ratio that, in some cases, can hit 1000 m2 per gram. At the microscopic level, to cut a bulk material into nanoparticles of 10-15 nm in size means to force half or more of the atoms to pass from the bulk to the surface. This operation requires additional energy, in the form of work against the attractive forces that pull surface atoms inward (see the next section for more details). In addition, in solids, the surface atoms display dangling bonds that are unsaturated and/or bear a partial electric charge [4]. Therefore, the increase of the surface-to-mass ratio in nanomaterials is thermodynamically mirrored by an overall, marked increase of the surface energy, which can be also viewed as an excess of surface energy with respect to the reference bulk material. The spontaneous tendency to relief this excess provides nanomaterials with their legendary enhanced activity.

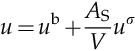

Is it possible to quickly describe the surface energy excess and estimate its order of magnitude? We can start by choosing a system and by splitting its total internal energy U into the bulk and surface contributions Ub and Uσ:

Now, we reformulate Equation (1.1) by using the intensive energies as follows:

where ub and uσ are the specific internal energies with respect to the system volume, V, and surface area, AS. Therefore, the total internal energy per unit volume, u, reads

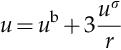

This equation correctly predicts that u increases as the surface-to-volume ratio increases and suggests this ratio as a fundamental parameter for the thermodynamic description of nanosystems. In the simple case the system is made of spheres of radius r, Equation (1.3) becomes

evidencing a direct relationship between u and the inverse of r.

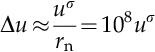

Thanks to Equation (1.4), we can finally estimate the increase (excess) of u when passing from a bulk system made of spheres of rb = 1 mm = 10− 3 m to a nanosystem made of spheres of rn = 10 nm = 10− 8 m. We obtain the impressive result (in SI units):

which says the increase in specific total ...