• Advances in nucleic acid sequencing technology have had a profound impact on the field of cancer genomics and have enabled the interrogation of the genetic basis of cancer at the single nucleotide level

• Cancer genomics has provided a detailed view of the complexity of the cancer genome, including the extraordinary ability to sustain and thrive on alterations of DNA

• Translating cancer genomics into clinically real time and actionable personalized medicine is beginning to be tested, although significant advances in the speed of providing molecular data, analysis, utilizing combination targeted agents and understanding clinical response or no response will require new generations of technology and bioinformatic tools

A Historical Perspective on the Development of Cancer Genomics

Several hundred years BC, Hippocrates is attributed with providing us with the term “carcinoma” and thus “cancer”, originating possibly from the image of finger-like extensions (veins) from a tumorous (main body of the tumor) breast lesion that shared resemblance to the shape of a crab. Around 400 years later, the Roman physician Celsus translated the Greek (karkinos) into the Latin word for crab, which led to the term “cancer” [1,2]. A relative late-comer to this nomenclature narrative, in 168 BC, Galen introduced the terms “oncos”, meaning “swelling” to describe tumors, leading to the term defining the field of oncology [3,4].

The next 2000 years witnessed several key events that helped to refine further the still ongoing main areas of cancer investigation and treatment. Maimonides in AD 1190 appears to have been the first to document surgically removing tumors [3]. The recognition of cancer clustering in distinct populations was introduced in 1713 with Razmazzini’s observation of the low cervical but high breast cancer incidence in nuns [2]. The observation that environmental and occupational exposures can be associated with increased incidence of specific cancers also became evident. In the first half of the 1800s, Recmier appears to have reignited the flare for nomenclature by writing about “metastasis” in 1829 to describe the movement of some cancers to different parts of the body [3]. Muller’s notes on the cellular origin of cancer also in 1838, and Paget’s subsequent “seed and soil” hypothesis over 50 years later in 1889, established the cognitive paradigm for the cell biological basis for cancer and the concept of microenvironmental niches [2,3]. The first half of the 20th century was ushered in by a set of remarkable observations in cancer biology that were made before the discovery of DNA. These included the theories of Rous regarding the potential viral origin of some cancers in 1910, derived from his work on avian sarcomas, and the concept of the somatic mutation theory of cancer by Boveri in 1914 that stemmed from his work on polyspermic development in invertebrates [5,6].

While not necessarily providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of carcinogenesis, the first half of the 20th century in many ways broke open the gates of cancer treatment. After being commissioned by the US government to understand the physiological consequences of nitrogen mustard gas used in warfare, Louis Goodman and Alfred Gilman recognized the key bone marrow toxicity of this agent and subsequently introduced its intravenous use for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies in 1946 [7]. Soon afterward in 1948, the antimetabolite aminopterin was used to treat several children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia by Farber and colleagues, a treatment built on the work of the chemist Subbarao [8]. A decade later, in 1958, Hertz, Li and colleagues reported the first cure of a metastatic tumor, namely a gestational-related choriocarcinoma, with another antimetabolite, methotrexate [9].

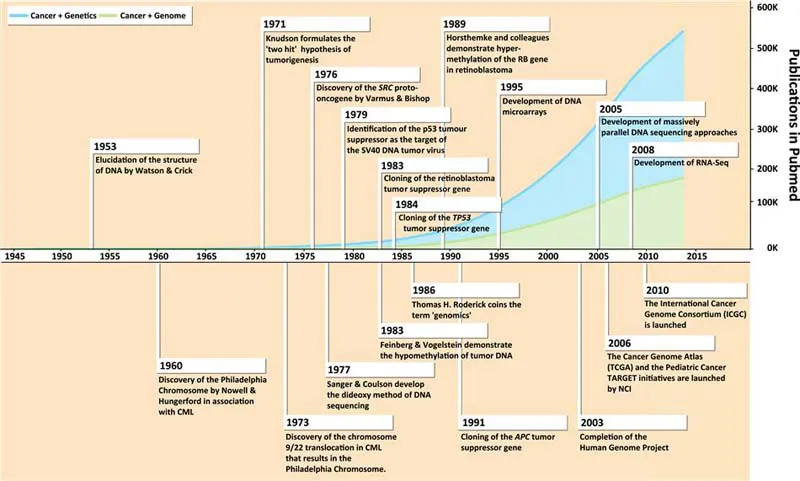

However, despite such encouraging forays into treating patients, few cures were achievable with surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. In this regard, the extraordinary efforts of Ms Mary Lasker following her husband’s death from cancer should not go unmentioned. Through her efforts and the Citizens Committee for the Conquest of Cancer through the 1960s, they challenged government, physicians and scientists to push forth with a “War on Cancer” [10–12]. And this was in spite of a significant number of naysayers who had concluded in various publications that we knew enough to cure cancer and all that was needed was to translate the knowledge that was available at the time. Such a lack of vision was thankfully thwarted by those who propitiously concluded that only through scientific discovery and its ongoing application would improvements in cancer outcomes occur. In 1971, the US National Cancer Act was passed by Congress and then President Nixon signed it into law within 2 weeks, an astonishingly rapid accomplishment on the part of government and one that should inform current, often stalled efforts [10–13]. The consequences of the above investment, along with other efforts across the globe [14], led to an infusion of intellectual engagement and financial support for conquering cancer. The results included the establishment of clinical trial groups, comprehensive cancer centers, an explosion of new anticancer agents from the lab and from nature, and the beginning of work focused on the biological understanding of cancer. This latter work built of course on the model and profound implications of the seminal discovery of the structure of the DNA double helix by Watson and Crick in 1953 [15], a discovery that would earn them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962, an accolade they shared with colleague Maurice Wilkins. In many ways, the journey to our present age of high-throughput and genome-wide discoveries in cancer biology began with this fundamental description of the fabric of life and, as such, this discovery makes a suitable origin point from which to chronicle the key events in cancer genomics in the last 60 years (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Historical milestones in cancer genomics. Key milestones in the field of cancer genomics are depicted starting with the elucidation of the structure of DNA by Watson and Crick in 1953. These milestones are depicted over a line graph of the total number of publications listed in the Pubmed database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the key-words “Cancer+(Genetics or Gene)” (in blue), or “Cancer+(Genomics or Genome)” (in green) from 1945 to 2013.

With the structure of the molecule of heredity in hand, the latter half of the 20th century saw a number of major contributions to our understanding of the biochemical and genetic underpinnings of cancer. These contributions included the identification of the “Philadelphia chromosome” as a genetic marker of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) by Nowell and Hungerford in 1960, and the subsequent identification of chromosomes 9 and 22 as the translocation partners underlying this anomalous chromosome by Rowley in 1973 [16,17]; the identification of the first cellular proto-oncogene, SRC, by Varmus and Bishop in the 1976 [18] leading to the realization that cellular genes could become deregulated resulting in tumorigenesis; and the identification of the p53 protein in 1979 as the primary molecular target underlying transformation by the DNA tumor virus, simian virus 40 (SV40) [18–20]. Empowered by the molecular tools developed for the study of tumor viruses, scientists studying cancer made many more seminal discoveries in the 1980s and early 1990s, including the identification of several tumor suppressor genes including retinoblastoma (RB) [21,22], the gene encoding p53 (TP53) [18–20,23,24] and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene [25–27]. All these discoveries were foreshadowed by Knudson’s “two hit” hypothesis of tumorigenesis and his pioneering epidemiological studies of retinoblastoma in 1971 [28], which laid the conceptual framework for how loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of a tumor suppressor gene contributes to cancer development. It was during the 1980s that non-genetic mechanisms of oncogene regulation were first identified. One such epigenetic mechanism of gene regulation was the loss of cytosine nucleotide methylation in CpG doublets, known as hypomethylation, which was first demonstrated by Feinberg and Vogelstein in 1983 and later shown to regulate the expression of oncogenes such as HRAS [29]. Soon after, in 1986, it would be demonstrated by Baylin et al. that increased CpG...