- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Receptors in the Evolution and Development of the Brain: Matter into Mind presents the key role of receptors and their cognate ligands in wiring the mammalian brain from an evolutionary developmental biology perspective. It examines receptor function in the evolution and development of the nervous system in the large vertebrate brain, and discusses rapid eye movement sleep and apoptosis as mechanisms to destroy miswired neurons. Possible links between trophic deficits and connectional diseases including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS are also discussed. This book is extremely useful to those with an interest in the molecular and cellular neurosciences, including those in cognitive and clinical branches of this subject, and anyone interested in how the incredibly complex human brain can build itself.- Provides an understanding of the key role receptors play in brain development and the selection process necessary to construct a large brain- Traces the evolution of receptors from the most primitive organisms to humans- Emphasizes the roles that REM sleep and apoptosis play in this selection via trophic factors and receptors- Describes the role that trophic factor-receptor interactions play throughout life and how trophic deficits can lead to connectional diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and ALS- Provides a potential mechanism whereby neuronal stem cells can cure these diseases

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Classes of receptors, their signaling pathways, and their synthesis and transport

Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Types of Receptors

G Protein Linked Receptors

(A) α-Helix. The stick figure (left) shows a right-handed α-helix with the N-terminus at the bottom and side chains R represented by the β-carbon. Hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms are indicated by blue lines. In this orientation, the carbonyl oxygens point upward, the amide protons point downward, and the R groups trail toward the N-terminus. Space filling models (middle) show a polyalanine α-helix. The end-on views show how the backbone atoms fill the center of the helix. A space filling model (right) of α-helix 5 from bacterial rhodopsin shows the side chains. Some key dimensions are 0.15 nm rise per residue, 0.55 nm per turn, and diameter of approximately 1.0 nm. (B) Stick figure and space filling models of an antiparallel β-sheet. The arrows indicate the polarity of each chain. With the polypeptide extended in this way, the amide protons and carbonyl oxygens lie in the plane of the sheet, where they make hydrogen bonds (blue lines) with the neighboring strands. The amino acid side chains alternate pointing upward and downward from the plane of the sheet. Some key dimensions are 0.35 nm rise per residue in a β-strand and 0.45 nm separation between strands. (C) Stick figure and space filling models of a parallel β-sheet. All strands have the same orientation (arrows). The orientations of the hydrogen bonds are somewhat less favorable than in an antiparallel sheet. (D and E) Stick figures of two types of reverse turns found between strands of antiparallel β-sheets. (F) Stick figure of an omega loop. Pollard TD, Earnshaw WC, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Johnson GT. Cell Biology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016 [Chapters 1, 3, 13–16, 21–24, 27, 30, 33 and 34]. Fig. 3.8, p. 38. With permission.

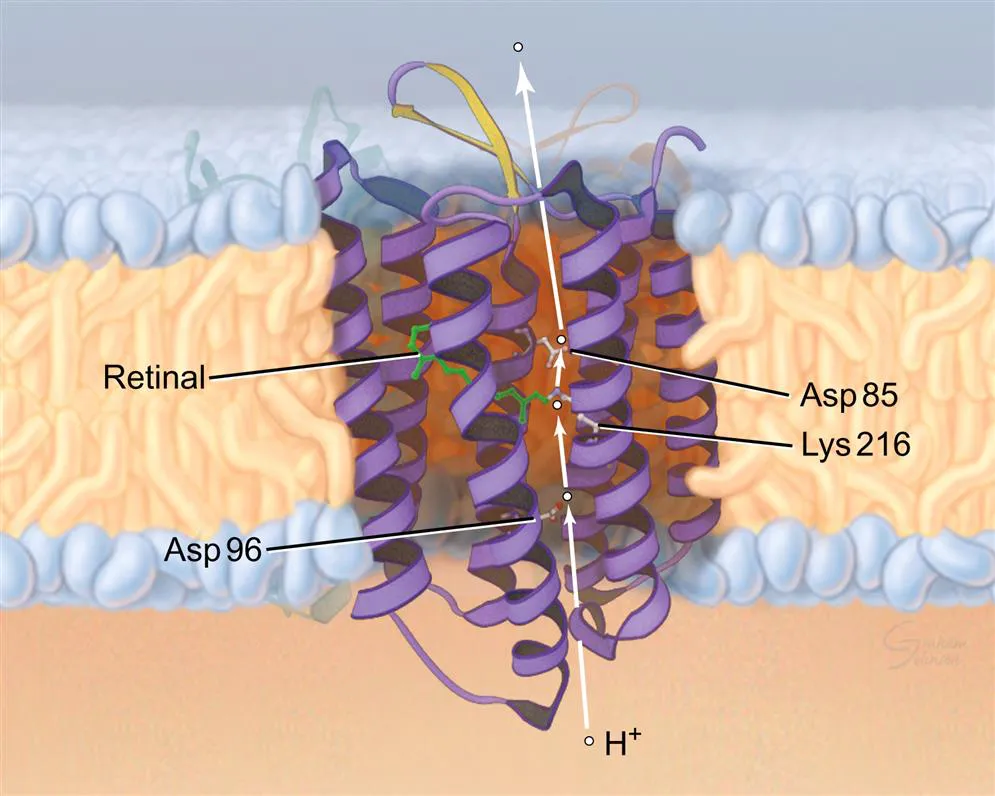

Numerous atomic structures, fast spectroscopic measurements of reaction intermediates, and analysis of a wide array of mutations revealed the pathway for protons through the middle of the bundle of seven α-helices. A cytoplasmic proton binds successively to Asp96, the Schiff base linking retinal to lysine 216 (Lys216), Asp85, and Glu204 before releasing outside the cell. Absorption of light by retinal drives conformational changes in the protein that favor the transfer of the proton across the membrane up its concentration gradient. Pollard TD, Earnshaw WC, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Johnson GT. Cell Biology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016 [Chapters 1, 3, 13–16, 21–24, 27, 30, 33, and 34]. Fig. 14.3, p. 38. With permission.

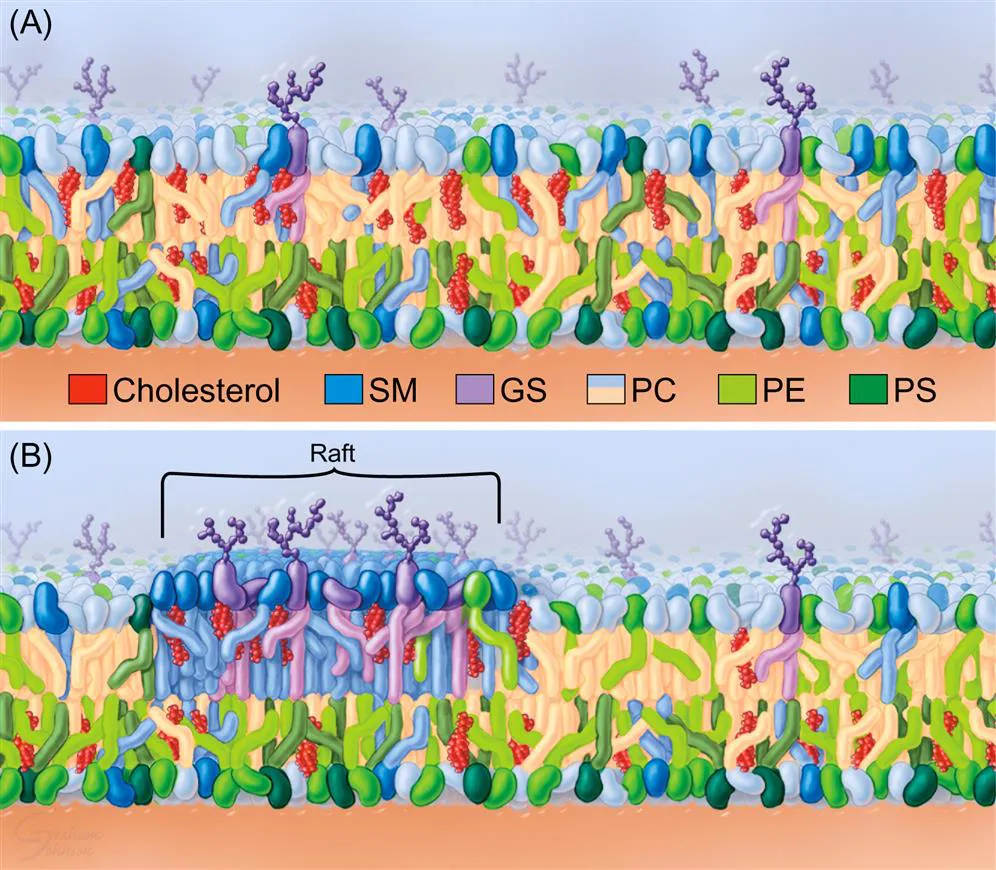

(A) Sphingomyelin (SM) and cholesterol form a small cluster in the external leaflet. GS, glycosphingolipid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine. PS is enriched in the inner leaflet. (B) Lipid raft in the outer leaflet ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Classes of receptors, their signaling pathways, and their synthesis and transport

- Chapter 2. The RNA world: receptors and their cognate ligands in Archaea, Bacteria, and Choanoflagellates

- Chapter 3. Dictyostelium discoideum, sponges, comb jellies, and hydra: the earliest animals

- Chapter 4. The growth cone and the synapse

- Chapter 5. Neuronal cell biology

- Chapter 6. Glial cells, the myelinated axon, and the blood-brain barrier

- Chapter 7. A testable theory on the wiring of the brain

- Chapter 8. Development of the cerebral cortex

- Chapter 9. The importance of sleep in selecting neuronal circuitry; programmed cell death/apoptosis

- Chapter 10. BDNF and endocannabinoids in brain development: neuronal commitment, migration, and synaptogenesis

- Chapter 11. Axon and dendrite guidance molecules and the extracellular matrix in brain development

- Chapter 12. Key receptors involved in laminar and terminal specification and synapse construction

- Chapter 13. Steroid hormones, glucocorticoids, and the hypothalamus

- Chapter 14. Receptors and the development of the enteric nervous system

- Chapter 15. Synaptic pruning and trophic factor interactions during development

- Chapter 16. Receptor-mediated mechanisms for drugs of abuse and brain development

- Chapter 17. Role of trophic factors and receptors in developmental disorders

- Chapter 18. Neuronal survival and connectional neurodegenerative diseases

- Chapter 19. Neuronal stem cells

- Chapter 20. Summary and conclusions

- Index