- 758 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Metal Fatigue: Effects of Small Defects and Nonmetallic Inclusions

About this book

Metal fatigue is an essential consideration for engineers and researchers looking at factors that cause metals to fail through stress, corrosion, or other processes. Predicting the influence of small defects and non-metallic inclusions on fatigue with any degree of accuracy is a particularly complex part of this.

Metal Fatigue: Effects of Small Defects and Nonmetallic Inclusions is the most trusted, detailed and comprehensive guide to this subject available. This expanded second edition introduces highly important emerging topics on metal fatigue, pointing the way for further research and innovation. The methodology is based on important and reliable results and may be usefully applied to other fatigue problems not directly treated in this book.

- Demonstrates how to solve a wide range of specialized metal fatigue problems relating to small defects and non-metallic inclusions.

- Provides a detailed introduction to fatigue mechanisms and stress concentration.

- This edition is expanded to address even more topics, including low cycle fatigue, quality control of fatigue components, and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Metal Fatigue: Effects of Small Defects and Nonmetallic Inclusions by Yukitaka Murakami in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mechanism of fatigue in the absence of defects and inclusions

Abstract

In order to evaluate quantitatively the effects of defects and inclusions we must first understand the basic mechanism of fatigue. Researchers who are mainly interested in the mechanism of fatigue on a microscopic scale may study the behaviour of dislocations during the fatigue process. In fact, active research in this field, including many experiments and theories on persistent slip bands and various dislocation structures, has led to understanding of some aspects of the fatigue phenomenon. However, study from the viewpoint of dislocation structure is somewhat qualitative, and has not so far been developed to a level that permits the quantitative solution of practical engineering problems. In this chapter, discussion of the fatigue mechanism is based on more macroscopic phenomena such as those observed with an optical microscope. The phenomena observed with an optical microscope are those that may be detected within one grain, in commercial materials, ranging in size from a few μm to several tens of μm. Thus, the process of initiation and propagation of so-called small cracks is perhaps the most important phenomenon discussed in this book. Although several theories of small cracks have been proposed, this chapter is restricted to the presentation of experimental evidence during the fatigue of unnotched specimens and to the derivation of practically useful conclusions.

Keywords

Mechanism of fatigue; knee point; steels; nonferrous metals; nonpropagating crack

In order to evaluate quantitatively the effects of defects and inclusions we must first understand the basic mechanism of fatigue. Researchers who are mainly interested in the mechanism of fatigue on a microscopic scale may study the behaviour of dislocations during the fatigue process. In fact, active research in this field, including many experiments and theories on persistent slip bands and various dislocation structures [1–19], has led to understanding of some aspects of the fatigue phenomenon. However, study from the viewpoint of dislocation structure is somewhat qualitative, and has not so far been developed to a level that permits the quantitative solution of practical engineering problems. In this chapter, discussion of the fatigue mechanism is based on more macroscopic phenomena such as those observed with an optical microscope. The phenomena observed with an optical microscope are those that may be detected within one grain, in commercial materials, ranging in size from a few μm to several tens of μm. Thus, the process of initiation and propagation of so-called small cracks is perhaps the most important phenomenon discussed in this book. Although several theories of small cracks have been proposed, this chapter is restricted to the presentation of experimental evidence during the fatigue of unnotched specimens, and to the derivation of practically useful conclusions.

1.1 What is a fatigue limit?

1.1.1 Steels

Fig. 1.1 shows a typical relationship between the applied stress, σ, and the number of cycles to failure, Nf, for unnotched steel specimens tested either in rotating bending or in tension–compression. This relationship is called an S–N curve, and the abrupt change in slope is called the ‘knee point’. Most steels show a clear knee point. The stress amplitude at the knee point is called the ‘fatigue limit’ since there is no sign of failure, even after the application of more than 107 stress cycles. In this book the fatigue limit of unnotched specimens is denoted σw0. Fig. 1.1 consists of two simple straight lines. If we predict, without prior knowledge, data for stresses lower than point B, then extrapolation of the line AB leads to the predicted line A→B→D. However, the observed result is B→C and not B→D. Therefore, we anticipate that something unexpected might be happening at σ=σw0. The interpretation of ‘fatigue limit’ which had been made in the era before the precise observation of fatigue phenomena on a specimen surface became possible was the ‘limit of crack initiation under cyclic stress’ [20–22]. In its historical context this interpretation was natural, and is still correct for some metals. However, this interpretation is inexact for most steels.

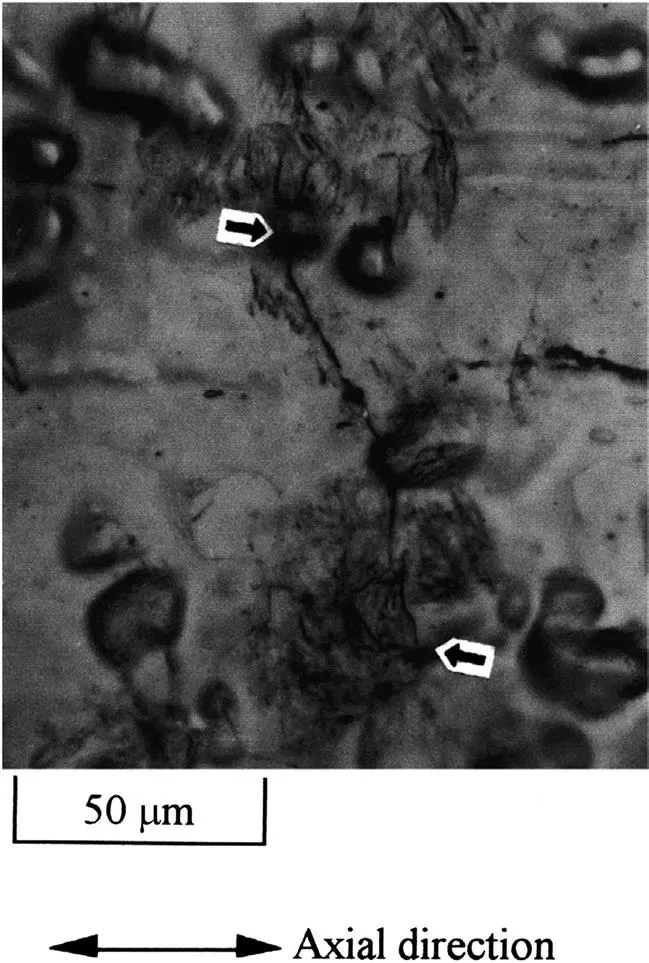

Fig. 1.2 shows the change in the surface appearance of an electropolished 0.13% C steel during a fatigue test at the fatigue limit stress, σw0. Slip bands appear at a very early stage, prior to crack initiation, and some of them become cracks. Some cracks remain within a grain, but others propagate through grain boundaries and then stop propagating. These cracks are called nonpropagating cracks in unnotched specimens. The maximum size of a nonpropagating crack in an annealed 0.13% C steel is of the order of 100 μm, which is much larger than the 34 μm average ferrite grain size. This experimental fact suggests that the fatigue limit is controlled by the average strength properties of the microstructure, and not directly by the grain size itself.1 The relationship between nonpropagating cracks of this kind and microstructures has been examined in detail [26–28]. The abrupt change (knee) at point B on the S–N curve in Fig. 1.1 is caused by the existence of nonpropagating cracks, such as those shown in Figs. 1.2 and 1.3. If the fatigue limit were correlated with crack initiation, this would imply that an S–N curve would not show a clear knee point (point B). This is because crack initiation would be determined by the condition of some individual grain out of the huge number of grains contained within one specimen. Accordingly, the crack initiation limit for individual grains varies almost continuously with the variation of test stress.

Thus, if the condition for crack initiation determined a fatigue limit, then the S–N curve would be expected to decrease continuously and gradually from a high stress level to a low stress level up to numbers of cycles larger than 107. However, what we actually observe in fatigue tests on low- and medium-carbon steels is a clear and sudden change in an S–N curve, and we can determine a fatigue limit to within a narrow band of ±5 MPa.

Summarising the available experimental data, and the facts derived from their analysis, the correct definition of a fatigue limit is ‘a fatigue limit is the threshold stress for crack propagation and not the critical stress for crack initiation’ [23–27]. The nonpropagating behaviour of fatigue cracks (in...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the first edition

- 1. Mechanism of fatigue in the absence of defects and inclusions

- 2. Stress concentration

- 3. Notch effect and size effect

- 4. Effect of size and geometry of small defects on the fatigue limit

- 5. Effect of hardness HV on fatigue limits of materials containing defects, and fatigue limit prediction equations

- 6. Effects of nonmetallic inclusions on fatigue strength

- 7. Bearing steels

- 8. Spring steels

- 9. Tool steels: effect of carbides

- 10. Effects of shape and size of artificially introduced alumina particles on 1.5Ni–Cr–Mo (En24) steel

- 11. Nodular cast iron and powder metal

- 12. Influence of Si-phase on fatigue properties of aluminium alloys

- 13. Ti alloys

- 14. Torsional fatigue

- 15. The mechanism of fatigue failure in the very high cycle fatigue (VHCF) life regime of N> 107 cycles

- 16. Effect of surface roughness on fatigue strength

- 17. Martensitic stainless steels

- 18. Additive manufacturing: effects of defects

- 19. Fatigue threshold in Mode II and Mode III, ΔKIIth and ΔKIIIth, and small crack problems

- 20. Contact fatigue

- 21. Hydrogen embrittlement

- 22. A new nonmetallic inclusion rating method by the positive use of the hydrogen embrittlement phenomenon

- 23. What is fatigue damage? A viewpoint from the observation of a low-cycle fatigue process

- 24. Quality control of mass production components based on defect analysis

- Appendix A. Instructions for a new method of inclusion rating and correlations with the fatigue limit

- Appendix B. Database of statistics of extreme values of inclusion size areamax

- Appendix C. Probability sheets of statistics of extremes

- Index