1.1.1 Beginning of agriculture

Hominids, i.e. early human-like species belonging to the genus Homo, evolved or appeared on Earth some three million years ago. Humans, Homo sapiens, evolved approximately 100–120 thousand years ago (Strait et al. 1997).

Once hominids came down from the trees to the ground, progress was rapid (comparatively speaking). They could now travel long distances in search of, or hunting for food. This was made possible by their being now bipedal. They could use their freed hands, so tool-making came naturally and group action could evolve. All of these factors promoted the development of language, and the brain started to expand. After spending a million years and more thus as hunter-gatherers, and crossing many a milestone on the way, partly by chance and partly by necessity, they finally stumbled into settled agriculture some 10–12 thousand years ago.

The discovery of agriculture was a watershed in human evolution, for it enabled humankind to settle down in one place. It ushered in the process of social and cultural evolution. The discovery and domestication of ‘dry’ crops within agriculture, viz. cereals, pulses or legumes, oilseeds and nuts, was another milestone. The crucial importance of these grains was that they were in equilibrium with the ambient atmosphere and hence ‘dry’, so these crops could be stored for long periods without spoilage. These grains enabled humankind to grow their main food once a year, yet serve them for the entire year. It could even leave a surplus that allowed the development of organisation and leisure for play of power, art and culture. Apparently barley, wheat, peas, lentils and flax were the first to be domesticated and grown. Cereals obviously were, and continue to be, pre-eminent among these crops because of their value as a supplier of energy and nutrition for sustenance.

1.1.2 Enter the ‘frail but economically mighty grass’

It is generally believed that agriculture first started around the Mesopotamian region in the valley between Euphrates and Tigris, or in the ‘fertile crescent’ spanning the Nile through Palestine to the confluence of Euphrates and Tigris (Storck and Teague 1952). If so, rice was probably not among the first cereals to be domesticated and cultivated. These are likely to have been barley and wheat. However, rice would not have been lagging far behind. Archaeological evidence in China, southeast Asia and the Indus Valley suggests that rice must be at least eight thousand years old, perhaps more (Grist 1959, Chang 2003). What is noteworthy is that despite possibly being marginally late in its domestication and sustained cultivation, this ‘frail but economically mighty grass’ (Chang 2003) has come to occupy such a preeminent position in human history.

1.1.3 Concentration and spread of rice cultivation

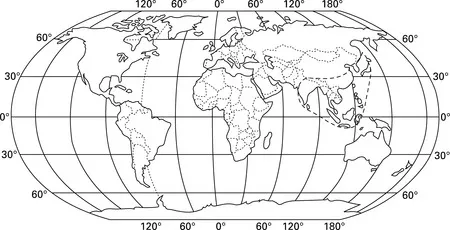

There are many surprising facts about rice. One of these is related to the extraordinary concentration of rice production in a small part of the world. A glance at Fig. 1.1 brings out this paradox. Approximately 90% or more of the world’s rice is produced in the relatively tiny area marked in the figure in south, southeast and northeast Asia – which we will refer to as the ‘rice countries of Asia’ or simply the ‘rice country’. And yet, as will be mentioned in many statements quoted below, roughly half the world’s population is said to depend on rice as their staple.

Fig. 1.1 World map highlighting ‘the rice countries of Asia’.

The reason for the extraordinary concentration of rice production has been hinted at by the following statement in the Rice Almanac brought out by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in collaboration with WARDA, CIAT and FAO of the United nations as a ready reckoner of rice facts to help the international rice research community (Maclean et al. (2002)):

‘Rice occupies an extraordinarily high portion of the total planted area in South, Southeast, and East Asia. This area is subject to an alternating wet and dry seasonal cycle and also contains many of the world’s major rivers, each with its own vast delta. Here, enormous areas of flat, low-lying agricultural land are flooded annually during and immediately following the rainy season. Only two major food crops, rice and taro, adapt readily to production under these conditions of saturated soil and high temperatures.’

D. H. Grist, an authority on rice of yesteryears, who wrote many editions of his well-known book Rice, wrote (Grist 1959):

‘The great rice areas of the Far East, such as the deltas of the Irrawaddy, Bhramputra, Mekong and the greater part of the Gangelia plain and the Krishnia areas are the results of erosion. Without erosion there would be far less land suitable for paddy. It is probable that paddy is grown because there is no other cereal which can grow under such high monsoon rainfall. Rice has enabled the populations of Asia to survive and indeed increase, because paddy checks – but does not entirely prevent – erosion. Had the people of Asia attempted to live by any other cereal they could not possibly have maintained their high density population for thousands of years. To prove the truth of this assertion one has only to compare the population density in countries of large rice production with those of other tropical countries where rice is not produced as the staple crop. Growing paddy necessitates water conservation and this in turn ensures soil conservation. Some of the terraced fields in Indonesia, the Philippines and south China are over two thousand years old and are typically conservation projects. This more than any other factor accounts for the predominance of rice as the staple food in southeast Asia, in countries of high rainfall.’

Despite the above extraordinary concentration of rice production in a relatively small area of the world, however, the other paradox is that rice is also extremely adaptable. It can be grown under a wide range of climatic conditions. It is today grown in every continent other than Antartica and in at least 100 countries from 45°N (under certain conditions up to even 53°N) to 40°S latitude, from sea level to approximately an altitude of 3000 metres and from being submerged under one to two metres of water (deep water rice) to dry upland areas. The Rice Almanac (Maclean et al. 2002) states:

‘Rice is produced in a wide range of locations and under a variety of climatic conditions, from the wettest areas in the world to the driest deserts. It is produced along Myanmar’s Arakan Coast, where the growing season records an average of more than 5,100 mm of rainfall, and at Al Hasa Oasis in Saudi Arabia, where annual rainfall is less than 100 mm. Temperatures, too, vary greatly. In the Upper Sind in Pakistan, the rice season averages 33 ° C; in Otaru, Japan, the mean temperature for the growing season is 17 ° C. The crop is produced at sea level on coastal plains and in delta regions throughout Asia, and to a height of 2,600 m on the slopes of Nepal’s Himalaya. Rice is also grown under an extremely broad range of solar radiation, ranging from 25% of potential during the main rice season in portions of Myanmar, Thailand, and India’s Assam state to approximately 95% of poten...