Innervation of striated muscle

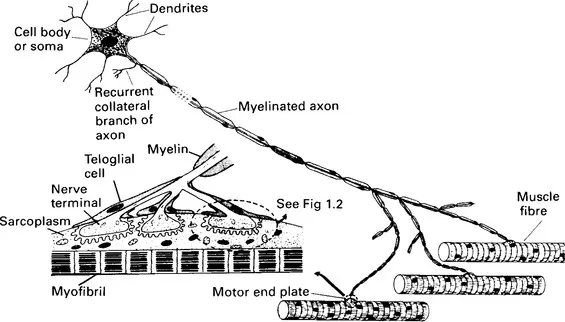

Striated muscles are innervated by somatic efferent nerve fibres which are fast-conducting myelinated group A axons with cell bodies in the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves in the brain stem, or in the anterior horns of grey matter in the spinal cord. These peripheral neurones are known as the lower motoneurones to distinguish them from the upper motoneurones involved in the central control of striated muscle movement. The axons of the lower motoneurones pass without interruption from the central nervous system to the muscles, where each axon branches extensively, the branching occurring at nodes of Ranvier. Through its extensive branching, a single axon innervates many muscle fibres (Figure 1.1). The lower motoneurone, together with the muscle fibres it innervates, form a functional unit called a motor unit (Liddell and Sherrington, 1925; Sherrington, 1930; Buchtal, 1960). The muscle fibres belonging to any one motor unit are probably all of the same type (i.e. fast pale, fast red or slow red intermediate, as defined below) (Edström and Kugelberg, 1968; Kugelberg and Edström, 1968) but they usually do not form a compact group; rather they lie scattered throughout the muscle. The characteristics of the units are determined by the type of muscle fibres they contain. Some units participate mainly in relatively rare, quick movements and contract rapidly; they are easily fatigued and are designated type FF. Others contribute to the maintenance of posture, contract slowly and are fatigue resistant (type S). Others are both fast and fatigue resistant and are designated type FR (Burke, 1981; Hennig and Lømo, 1985). The number of muscle fibres within a motor unit differs according to the delicacy of the movement that the muscle is capable of producing. For example, in the small muscles that move the fingers and the external rectus muscles of the eye, each nerve axon supplies only 5−15 muscle fibres, whereas in the large limb and back muscles, which are less capable of fine delicate movements, each axon supplies over a thousand muscle fibres (Buchtal, 1960).

Figure 1.1 Diagram of a motor unit containing focally innervated muscle fibres. A motor endplate is enlarged as the inset on the left, and a unit of this is further enlarged in Figure 1.2. (From Bowman, W. C. and Rand, M. J. Textbook of Pharmacology, 2nd edn, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1980, with permission)

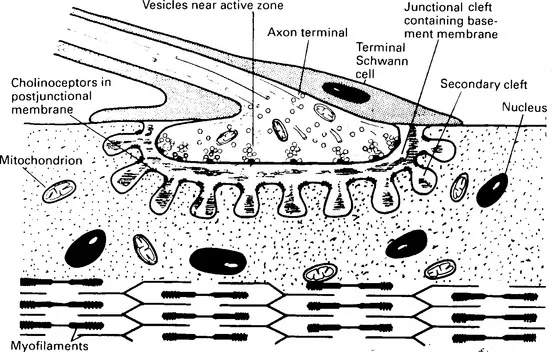

As it aproaches a muscle fibre, the terminal branch of an axon loses its myelin sheath, and, where it makes contact with the muscle fibre, it breaks up into a number of short twigs (telodendria) that lie in gutters, the junctional clefts, in the muscle fibre membrane. The surface of the junctional cleft in apposition to the nerve ending is thrown into folds, the junctional folds, forming so-called secondary clefts. At its narrowest, the junctional gap between the plasma membranes of nerve ending (axolemma) and muscle fibre (sarcolemma) is about 60 nm wide. The gap includes a layer of ill-defined material, the basement membrane, or basal lamina. The basement membrane is a material rich in mucopolysaccharides and with some of the characteristics of collagen. It fills the whole of the junctional gap and extends into the secondary clefts formed by the junctional folds. It probably functions both as a structural support and as a selective filter which must allow for the rapid diffusion of acetylcholine. Hirokawa and Heuser (1982) prepared deep-etch images of frog neuromuscular junctions quick frozen directly from life, and obtained an unusually distinct view of the basement membrane which resembled barbed wire lying in the junctional cleft. Its appearance arose from the wisps of material that extend from it to both pre- and postjunctional membranes. The basement membrane contains much of the acetylcholinesterase of the junction embedded within it.

The terminal Schwann cells (teloglia) of the axon twigs form ‘lids’ to the junctional clefts so that the neuromuscular junctions are enclosed. In the junctional region of the muscle fibre there is an accumulation of sarcoplasm containing many mitochondria, ribosomes and nuclei. The whole junctional structure is traditionally called the motor endplate (Krause, 1863), while the specialized postjunctional membrane, together with its immediately underlying structures, is called the sole plate. There is some confusion of terminology, however, as many authors, especially English-speaking authors, use the term ‘motor endplate’ to designate only the postjunctional membrane, in which case motor endplate and sole plate become synonymous. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 illustrate the general arrangement of the neuromuscular junction. For detailed descriptions, reviews and original papers may be consulted (Bowden and Duchen, 1976; Desaki and Uehara, 1981; Waser, 1983).

Figure 1.2 Diagram of neuromuscular junction enlarged from the motor endplate of Figure 1.1. The axon terminal contains mitochondria, microtubules and acetylcholine-containing vesicles

Focally and multiply innervated muscle fibres

Muscle fibres that receive their innervation at a focal point on their membranes are described as focally innervated (Figure 1.1). Most mammalian muscle fibres are of this type; the focal motor endplates of muscle fibres innervated by spinal nerves are usually about midway between the origin and the insertion of the muscle fibres. Some very long muscle fibres may possess two or three foci of innervation, probably supplied by the same axon; such muscle fibres are still regarded as focally innervated. Focally innervated muscle fibres are innervated by fast-conducting axons of the Aα group. While remaining within this group, axons supplying focally innervated slow-contracting intermediate muscle fibres conduct slightly more slowly than do those innervating fast-contracting muscle fibres. The motor endplates on fast pale muscle fibres form a conspicuous elevation and are sometimes called en plaque endplates; there are several junctional clefts and an associated arborization of nerve ending twigs making up the composite endplate and the clefts are thrown into deep junctional folds. Motor endplates on fast red fibres are more simple, with few junctional folds, and those on slow red intermediate fibres fall between these extremes. The different types of muscle fibre referred to here (fast pale, fast red and slow red intermediate) are defined below.

Multiply innervated fibres receive a dense innervation all over their membranes from many nerve endings. For example, it has been estimated that each multiply innervated fibre of the chicken anterior latissimus dorsi muscle has about 80 motor endplates (Ginsborg, 1960b). Multiply innervated fibres are common in certain muscles of birds (Ginsborg, 1960b; Shehata and Bowden, 1960; Koenig, 1970), some snakes (Hess, 1965), amphibia (Katz and Kuffler, 1941; Kuffler and Vaughan Williams, 1953) and fish (Nakajima, 1969; Korneliussen, 1973). In mammals, including man, the extraocular muscles (Gerebtzoff, 1959; Kupfer, 1960; Hess, 1961b; Zenker and Anzenbacher, 1964; Bach-y-Rita and Ito, 1966; Teräväinen, 1968, Teräväinen, 1972), the intrinsic laryngeal muscles (Keene, 1961; Manolov, Penev and Itchev, 1963), the striated muscle in the upper oesophagus and in the middle ear (Csillik, 1965), and the facial muscles (Bowden and Mahran, 1956; Kadanoff, 1956) contain a proportion of multiply innervated fibres. In many instances, the multiple endplates on any one multiply innervated muscle fibre appear to be innervated by the same neurone, but in others there is probably polyneuronal innervation. The axons innervating multiply innervated fibres are usually of the Aγ group. Each terminal axon branch ends in a number of small swellings resembling a bunch of grapes and known as en grappe terminations. The endplates are of the relatively simple type with smooth junctional clefts.

Muscle fibres in the fetus are multiply innervated but during postnatal development mammalian muscle fibres undergo an orderly process of elimination of neuromuscular junctions, whereby each loses all but one of the multiple inputs with which it is endowed at birth (Brown, Jansen and Van Essen, 1976). Experimental procedures that increase or decrease neuromuscular activity cause a corresponding increase or decrease in the overall rate of elimination of junctions (Thompson, 1986), but the underlying mechanism is not yet understood. The elimination process ensures that each motoneurone forms an independent motor unit containing a certain number of muscle fibres.