B.K. Lee, Y.H. Yun and K. Park, Purdue University, USA

Abstract:

Treating cancer requires multiple levels of investigation. Anticancer agents need to be developed through in vitro testing, in vivo animal experiments, followed by clinical studies. Most anticancer drugs are highly hydrophobic and are formulated with excipient materials that increase the water solubility of the drugs, such as co-solvents, liposomes, lipids, polymer micelles, and hydrotropic agents. Anticancer drugs cause serious side effects, so there is a great need to deliver the majority of drug to target cancer cells or solid tumors more specifically. This requires development of formulations for targeted delivery. Delivery systems in nanosize, commonly-called nanovehicles, have been frequently used for this purpose. Nanovehicles are also used as an imaging agent for theranosis and as a photothermal agent for thermal ablation of cancer cells. Nanovehicles are engineered to be responsive to environmental changes in temperature or pH for efficient release of a drug at a target site. While nanovehicles have increased the proportion of the drug delivered to target tumors, the absolute amount of the drug delivered is still very small. New polymeric delivery systems may be necessary to achieve the goal of targeted drug delivery. The testing of the various drugs and delivery systems in vivo is difficult, thus it is highly desirable to develop in vitro model systems that can simulate in vivo conditions in humans with the highest fidelity. Proper use of existing biomaterials and development of new biomaterials are necessary to achieve these goals.

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Historic approaches to cancer treatment

The history of cancer is extensive. Although the first written document on cancer may be traced only back to ancient Egypt, around 300 BC (Deeley, 1983), cancer must have existed since the origin of humans. Despite the 50 000 years of modern human history, it was less than 100 years ago when cancer chemotherapy first began using nitrogen mustard (Gilman, 1963). While not successful, such an approach led to testing of another drug, methotrexate, opening the door to combination chemotherapy. To alleviate the often brutal side effects of chemotherapy, so-called targeted treatment was developed. The targeted treatment here is based on monoclonal antibodies that interact with specific target proteins on the cancer cell surface, or molecules that interact with receptors existing only on cancer cells. This is the same as the ‘magic bullet’ concept by Paul Ehrlich (Winau et al., 2004). It is noted that the targeted treatment is different from ‘targeted delivery’ of a drug to the target cancer cells only (Bae and Park, 2011). Although the goals of the two approaches, i.e., targeted treatment and targeted drug delivery, are the same in maximizing the drug efficacy with minimal side effects, the two terms need to be distinguished as their approaches are fundamentally different.

1.1.2 Current and developing approaches to cancer treatment

As of now, it is difficult to cure cancer. The most efficacious therapies are preventing metastasis through early detection and stopping/slowing of cancer cells using cancer drugs, e.g., imatinib (Gleevec®) (Klein and Levitzki, 2007). Chemotherapy requires that the side effects of long-term treatment are manageable. To make the cancer treatment more effective and preventive, improved drug-delivery systems can be developed to make better use of existing drugs and to promote drugs under development that have difficult physicochemical properties. This requires advanced drug-delivery systems that are usually based on biomaterials with various properties. For this reason, this chapter briefly reviews biomaterials that have been used in cancer treatment.

1.2 Biomaterials used in cancer therapeutics

Cancer therapeutics includes preventive medicine, diagnosis, radiation therapy, hyperthermia, photodynamic therapy, chemotherapy, and surgical therapy. Recently, the biomaterials used in delivery of drugs (i.e., therapy) were also used in delivery of diagnostic agents, and this led to a new discipline called theranosis (therapy and diagnosis). While there are many biomaterials suited for targeted drug delivery and theranosis, not many of them have evolved into testing in human patients. This is largely due to the reluctance of the pharmaceutical industry to test new excipients that were not used before in the clinical drug formulations approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This is something that the drug-delivery scientists must understand. When a pharmaceutical company develops a new anticancer drug, testing its safety and efficacy is the biggest concern. Adding an unproven excipient (i.e., any biomaterial that is not a drug) to a potentially blockbuster drug is too risky. If the formulation fails, it is not clear whether it is due to the drug itself or due to the use of an unproven excipient. Furthermore, the cost of testing a new excipient in human clinical trials to show its safety is not trivial. Overall, it has been very difficult to introduce new biomaterials into clinical applications. Those scientists who are aware of these limitations tend to use so-called ‘generally regard as safe’ (GRAS) materials that are already proven to be safe for use in humans. While formulation scientists continue their search for novel biomaterials for improving cancer therapeutics, they need to consider utilizing GRAS materials that may have better acceptance by the pharmaceutical industry. The number of GRAS materials that can be used in cancer therapeutics is limited, and more GRAS materials need to be identified in the future to provide more flexibility in designing drug-delivery systems for cancer therapeutics.

In addition to cancer therapeutics, biomaterials are also important in studying cancers using in vitro models. Before animal and clinical studies are conducted, in vitro models are used to understand the mechanisms of drug action and drug-delivery systems. For proper study of drug delivery to solid tumors, development of three-dimensional (3D) tumor sphere models is necessary. Many biomaterials have been used in development of in vitro 3D tumor spheroids and tumor spheroid-containing devices.

1.3 Materials used in anticancer formulations

1.3.1 Materials for improving drug solubility

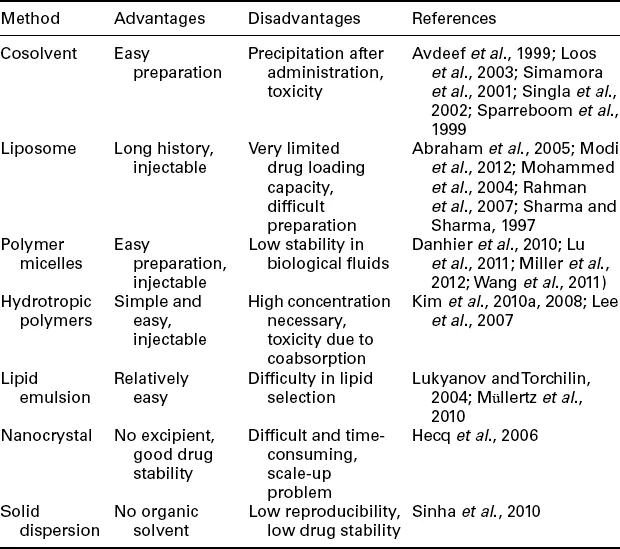

The majority of anticancer drugs currently under clinical use are small molecules which are often not soluble in water. The poor solubility has been the main difficulty in formulating anticancer drugs. Many times the aqueous solubility of a new drug candidate is so low that it cannot be developed into a clinically useful drug. Several different approaches have been developed to increase the water solubility of anticancer drugs. The commonly used approaches are listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Formulations for improving water solubility of poorly soluble drugs

One of the most widely used approaches for increasing the solubility of poorly soluble drugs is using cosolvent systems. A poorly soluble drug is first dissolved in an organic solvent, e.g., Cremophor EL for paclitaxel and polysorbate for docetaxel (Loos et al., 2003; Singla et al., 2002; Sparreboom et al., 1999). The solution is diluted with aqueous solution before administration by intravenous (IV) administration. Dilution in water usually results in precipitation of a poorly soluble drug, but the solution can remain stable at least for several hours for administration without any problem. Liposome formulations have also been used widely in delivering poorly soluble drugs (Modi et al., 2012; Mohammed et al., 2004; Sharma and Sharma, 1997). Liposomal formulation of doxorubicin has also shown other benefit of reducing cardiotoxicity as compared with unencapsulated drug (Abraham et al., 2005; Barenholz, 2012; Rahman et al., 2007). Polymer micelles have been frequently used for dissolution of poorly soluble drugs in their hydrophobic core. One of the most widely used polymer micelles is copolymers of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and poly(lactic-go-glycolic acid) (PLGA) (Danhier et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Polymer micelles are not stable in blood and may become disrupt...