High Performance Silicon Imaging

Fundamentals and Applications of CMOS and CCD Sensors

- 522 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

High Performance Silicon Imaging: Fundamentals and Applications of CMOS and CCD Sensors, Second Edition, covers the fundamentals of silicon image sensors, addressing existing performance issues and current and emerging solutions. Silicon imaging is a fast growing area of the semiconductor industry. Its use in cell phone cameras is already well established, with emerging applications including web, security, automotive and digital cinema cameras. The book has been revised to reflect the latest state-of-the art developments in the field, including 3D imaging, advances in achieving lower signal noise, and new applications for consumer markets.The fundamentals section has also been expanded to include a chapter on the characterization and testing of CMOS and CCD sensors that is crucial to the success of new applications. This book is an excellent resource for both academics and engineers working in the optics, photonics, semiconductor and electronics industries.- Covers the fundamentals of silicon-based image sensors and technical advances, focusing on performance issues- Looks at image sensors in applications, such as mobile phones, scientific imaging, and TV broadcasting, and in automotive, consumer and biomedical applications- Addresses the theory behind 3D imaging and 3D sensor development, including challenges and opportunities

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Fundamental principles of photosensing

b Central Institute of Engineering, Electronics and Analytics ZEA-2—Electronic Systems, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, Jülich, Germany

Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Introduction

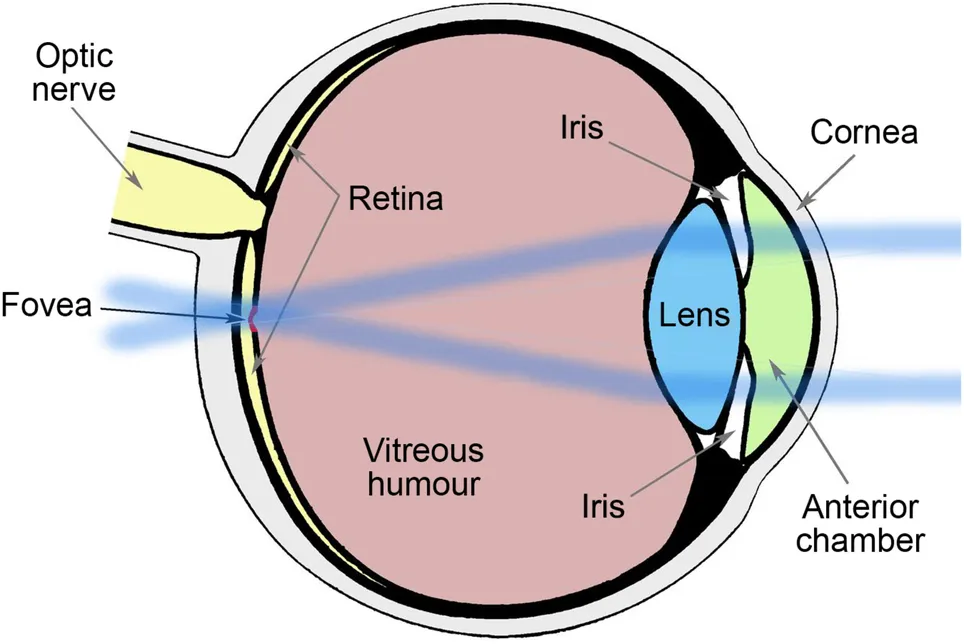

1.2 The human vision system

| Parameter | Rods | Cones |

|---|---|---|

| Operating conditions | Dim light | Daylight |

| Sensitivity | High | Low |

| Spatial resolution | Poor | Good |

| Temporal resolution | Poor | Good |

| Maximal sensitivity | Blue-green | Yellow-green |

| Directional sensitivity | Slight | Marked |

| Rate of dark adaptation | Slow | Fast |

| Color vision | Absent | Present |

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part One: Fundamentals

- Part Two: Applications

- Index