- 532 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Imaging of the Human Brain in Health and Disease

About this book

Brain imaging technology remains at the forefront of advances in both our understanding of the brain and our ability to diagnose and treat brain disease and disorders. Imaging of the Human Brain in Health and Disease examines the localization of neurotransmitter receptors in the nervous system of normal, healthy humans and compares that with humans who are suffering from various neurologic diseases.Opening chapters introduce the basic science of imaging neurotransmitters, including sigma, acetylcholine, opioid, and dopamine receptors. Imaging the healthy and diseased brain includes brain imaging of anger, pain, autism, the release of dopamine, the impact of cannabinoids, and Alzheimer's disease.This book is a valuable companion to a wide range of scholars, students, and researchers in neuroscience, clinical neurology, and psychiatry, and provides a detailed introduction to the application of advanced imaging to the treatment of brain disorders and disease.- A focused introduction to imaging healthy and diseased brains- Focuses on the primary neurotransmitter release- Includes sigma, acetylcholine, opioid, and dopamine receptors- Presents the imaging of healthy and diseased brains via anger, pain, autism, and Alzheimer's disease

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Neuroimaging of Addiction

Abstract

Keywords

Acknowledgments

1 Introduction

2.1 Magnetic Resonance-Based Imaging Techniques

2.1.1 Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging

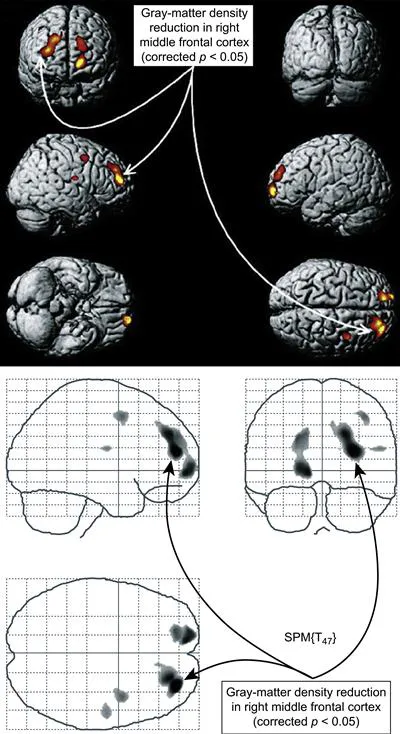

Drug Exposure can Trigger Abnormalities in Prefrontal Cortex and Other Brain Regions

2.1.2 Functional MRI

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Chapter One. Neuroimaging of Addiction

- Chapter Two. Brain PET Imaging in the Cannabinoid System

- Chapter Three. Brain Imaging of Cannabinoid Receptors

- Chapter Four. Human Brain Imaging of Opioid Receptors: Application to CNS Biomarker and Drug Development

- Chapter Five. Brain Imaging of Sigma Receptors

- Chapter Six. Human Brain Imaging of Acetylcholine Receptors

- Chapter Seven. Human Brain Imaging of Adenosine Receptors

- Chapter Eight. Human Brain Imaging of Dopamine D1 Receptors

- Chapter Nine. Human Brain Imaging of Dopamine Transporters

- Chapter Ten. Imaging of Dopamine and Serotonin Receptors and Transporters

- Chapter Eleven. Imaging the Dopamine D3 Receptor In Vivo

- Chapter Twelve. Dopamine Receptors and Dopamine Release

- Chapter Thirteen. Dopamine Receptor Imaging in Schizophrenia: Focus on Genetic Vulnerability

- Chapter Fourteen. Human Brain Imaging in Tardive Dyskinesia

- Chapter Fifteen. Human Brain Imaging of Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Chapter Sixteen. Radiotracers Used to Image the Brains of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease

- Chapter Seventeen. Human Brain Imaging of Anger

- Chapter Eighteen. Imaging Pain in the Human Brain

- Chapter Nineteen. Imaging of Neurochemical Transmission in the Central Nervous System

- Chapter Twenty. Characterizing Recovery of the Human Brain following Stroke: Evidence from fMRI Studies

- Index