eBook - ePub

Fundamental Aliphatic Chemistry

Organic Chemistry for General Degree Students

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamental Aliphatic Chemistry

Organic Chemistry for General Degree Students

About this book

Organic Chemistry for General Degree Students is written to meet the requirements of the London General Internal examination and degree examinations of a similar standing. It will also provide for the needs of students taking the Part 1 examination for Graduate Membership of the Royal Institute of Chemistry, or the Higher National Certificate, whilst the treatment is such that Ordinary National Certificate courses can be based on the first two volumes

Within the limits broadly defined by the syllabus, the aim of this first volume is to provide a concise summary of the important general methods of preparation and properties of the main classes of aliphatic compounds. Due attention is paid to practical considerations with particular reference to important industrial processes. At the same time, the fundamental theoretical principles of organic chemistry are illustrated by the discussion of a selection of the more important reaction mechanisms. Questions and problems are included, designed to test the student's appreciation of the subject and his ability to apply the principles embodied therein. A selection of questions set in the relevant examinations is also included.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fundamental Aliphatic Chemistry by P. W. G. Smith,A. R. Tatchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Introduction

Publisher Summary

Organic chemistry is the chemistry of carbon compounds, excluding compounds such as the carbonates, bicarbonates, carbon monoxide, and the metallic carbonyls. It was clearly realized by the early organic chemists that no attempt could be made on the structural elucidation of a particular compound until both the nature and relative proportions of the elements present in its molecule had been determined. This approach led to the establishment of the principal methods of the qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis of organic substances. The organic substances that contain metallic elements leave behind an incombustible residue after ignition that may be submitted to the usual methods of inorganic qualitative analysis. The detection of the elements nitrogen, sulfur, and the halogens in an organic compound is most conveniently carried out by fusion with sodium, which is known as Lassaigne method. The next step in determining the nature of an organic compound is the quantitative analysis of those elements found by the qualitative tests. This enables the relative atomic proportions of the molecule to be calculated and from the molecular weight of the substance, the absolute number of atoms of each element present in one molecule of the organic compound is ascertained.

Organic chemistry is the chemistry of carbon compounds (excluding such compounds as the carbonates, bicarbonates, carbon monoxide and the metallic carbonyls). This broad definition derives from studies carried out at the beginning of the nineteenth century on compounds isolated from animal and vegetable materials (i.e. of organic origin) as distinct from those isolated from mineral sources (i.e. of inorganic origin). In the initial classification of organic compounds it became convenient to distinguish those which from their structure and reactivity were closely related to the compound benzene, as distinct from those which were structurally related to the naturally occurring fatty acids. The former, from their wide distribution in the pleasant-smelling plant resins, gums and oils were termed aromatic compounds, whilst the latter were designated as aliphatic compounds.

Early studies in organic chemistry were frequently stimulated by the observation that certain plant and animal extracts possessed medicinal, nutritional or colouring (dyeing) properties. Work was therefore directed initially to an examination of the means of handling such extracts in order to isolate the ‘active principle’ (substantially free from the other numerous constituents) which was responsible for these specific characteristics. It was then possible to embark upon studies directed towards the elucidation of the manner in which the individual atoms in a molecule of the pure compound were linked together (i.e. the determination of the structure of the molecule).

Organic substances were always found to give carbon dioxide and water upon burning in oxygen, showing the presence of the elements carbon and hydrogen. As the number of such isolated substances increased it became apparent that other elements were often also present, those most commonly found being oxygen, nitrogen, the halogens and sulphur. It was clearly realized by the early organic chemists that no attempt could be made on the structural elucidation of a particular compound until both the nature and relative proportions of the elements present in its molecule had been determined. This approach led to the establishment of the principal methods of qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis of organic substances. Since this analytical information is still the vital first step in any structural investigation, and since all the pure organic compounds ever isolated from natural sources or synthesized in the laboratory have been submitted to this process, it is pertinent to consider briefly an outline of the methods which are now available. The full practical details are to be found in any practical organic chemistry book.

Qualitative Analysis

Those organic substances which contain metallic elements leave behind an incombustible residue after ignition which may be submitted to the usual methods of inorganic qualitative analysis.

The detection of the elements nitrogen, sulphur and the halogens in an organic compound is most conveniently carried out by fusion with sodium (the Lassaigne method). A convenient technique is to drop some of the compound to be examined on to sodium pre-heated in a Pyrex test-tube. During the subsequent vigorous reaction sodium cyanide, sulphide or halide is formed if the organic compound contains nitrogen, sulphur or halogen respectively. Methanol is added to the cooled tube to decompose unreacted sodium and the residue extracted with boiling distilled water to dissolve the sodium salts.

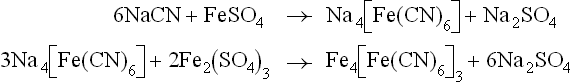

The cyanide ion is detected by adding aqueous ferrous sulphate solution to a portion of the extract, boiling to achieve some aerial oxidation of ferrous ions to ferric ions, and acidifying with sulphuric acid. A blue precipitate of ferric ferrocyanide (Prussian blue) indicates the presence of nitrogen in the original substance.

The halide ion is detected by acidifying a portion of the fusion extract with nitric acid and boiling to expel hydrogen cyanide (or sulphide) if these are present. Aqueous silver nitrate solution is then added to precipitate any silver halide. The nature of the halogen may be deduced in the usual way.

The sulphide ion is detected in the aqueous extract by the addition of a solution of sodium nitroprusside, when an unmistakable violet coloration is produced if sulphide ions are present. Alternatively the addition of sodium plumbite solution gives a black precipitate of lead sulphide.

Quantitative Analysis

The next step in determining the nature of an organic compound is the quantitative analysis of those elements found by the qualitative tests above. This enables the relative atomic proportions of the molecule to be calculated (the empirical formula), and thence from the molecular weight of the substance, the absolute number of atoms of each element present in one molecule of the organic compound is ascertained (the molecular formula).

For this analysis the compound must be rigorously purified by either careful and repeated distillations or by several recrystallizations.

The micro-analytical techniques which are available at the present time enable a complete quantitative analysis to be performed on as little as 5–15 mg of material. Details of methods used are to be found in suitable textbooks on practical organic chemistry, but the principles of these procedures are outlined below.

The basic principle of the carbon:hydrogen determination is that an organic compound when pyrolysed in oxygen gives quantitatively carbon dioxide and water, both of which may be collected and weighed in a suitable trapping system, which requires some modification if elements other than carbon, hydrogen or oxygen are present.

The nitrogen content of an organic compound is commonly determined by measuring the volume of nitrogen gas evolved (corrected to S.T.P.) when an organic substance is heated with copper oxide (Dumas method). The halogen is determined as silver halide which is produced when the substance is heated in a sealed tube with silver nitrate and nitric acid at 200° (Carius method). The sulphur present in an o...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Atomic Structure and Chemical Bonding

- Chapter 3: The Paraffins

- Chapter 4: Halogen Derivatives of Aliphatic Hydrocarbons

- Chapter 5: Aliphatic Alcohols and Ethers

- Chapter 6: The Structure of Multiple Bonds

- Chapter 7: The Olefins

- Chapter 8: Acetylenes and Diolefins

- Chapter 9: Aliphatic Aldehydes and Ketones

- Chapter 10: Aliphatic Monocarboxylic Acids and their Derivatives

- Chapter 11: The Synthetic Uses of Grignard Reagents, β-Keto Esters and Diethyl Malonate

- Chapter 12: Introduction to Stereoisomerism

- Chapter 13: Aliphatic Nitro Compounds and Amines

- Chapter 14: Aliphatic Sulphur-containing Compounds

- Questions

- Answers to Problems

- Index