eBook - ePub

Fed-Batch Fermentation

A Practical Guide to Scalable Recombinant Protein Production in Escherichia Coli

- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fed-Batch Fermentation

A Practical Guide to Scalable Recombinant Protein Production in Escherichia Coli

About this book

Fed-batch Fermentation is primarily a practical guide for recombinant protein production in E. coli using a Fed-batch Fermentation process. Ideal users of this guide are teaching labs and R&D labs that need a quick and reproducible process for recombinant protein production. It may also be used as a template for the production of recombinant protein product for use in clinical trials. The guide highlights a method whereby a medium cell density - final Ods = 30-40 (A600) - Fed-batch Fermentation process can be accomplished within a single day with minimal supervision. This process can also be done on a small (2L) scale that is scalable to 30L or more. All reagents (media, carbon source, plasmid vector and host cell) used are widely available and are relatively inexpensive. This method has been used to produce three different protein products following cGMP guidelines for Phase I clinical studies.

- This process can be used as a teaching tool for the inexperienced fermentation student or researcher in the fields of bioprocessing and bioreactors. It is an important segue from E. coli shake flask cultures to bioreactor

- The fed-batch fermentation is designed to be accomplished in a single day with the preparation work being done on the day prior

- The fed-batch fermentation described in this book is a robust process and can be easily scaled for CMO production of protein product

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fed-Batch Fermentation by G G Moulton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Microbiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to fermentation

Abstract

The use of yeast or microbial cells for the production of a foreign protein has changed the approach of medical research to finding healthcare solutions. The application of recombinant systems has become mainstream in treatment of disease. One of the most important aspects of this new scientific discipline is the ability to design a cell line or strain, in the case of bacterial or yeast recombinant systems that can be grown under controlled conditions, to produce significant quantities of a recombinant protein. Recently, E. coli has been the predominant bacteria in research and production laboratories and plays a key role in the development of modern biological engineering and industrial microbiology, enabling foreign proteins to be produced in a prodigious and cost-effective way. This type of cell growth and production is called fermentation and its history and use will be discussed along with current developments and applications of recombinant technology.

Key words

E. coli

fermentation

recombinant DNA

yeast

nucleic acids

bacteria

RNA

phosphate plasmid DNA

recombinant protein

media

fed-batch

inclusion body

acetate

glucose

IPTG

cell factory

1.1 A brief history of early fermentation and the discovery of DNA

It has been known for thousands of years that the fermentation of carbon sources from grain and/or honey (for beer or mead) and grapes or other fruit (for wine) will yield a beverage, which when fermented correctly is quaffable as well as entertaining to the senses (a feeling of well-being or intoxication). In fact, scientists have shown through chemical analysis that jars found in northern China contained a mixed fermented beverage made from rice, honey and fruit made 9000 years ago [1]. Throughout human history, cultures from Greece, Egypt, China and the Americas have produced fermented concoctions for many reasons, including religious, celebratory or personal consumption. In Egypt, the god Osiris was believed to have invented beer. Because of this, beer was thought of as an important part of society and family and brewed on a daily basis [2].

In Greece, by the 16th century bc, the fermentation of grapes into wine was common. By the 3rd century bc, the moderate use of wine was thought of by many, including Plato and Hippocrates, as both beneficial to health and happiness and of therapeutic or medicinal value [3]. During this time, the poet Eubulus stated that three bowls (glasses) of wine were the ideal amount to consume, which roughly equals one 750 ml bottle of wine. The cult of Dionysus believed strongly that wine or intoxication from wine would bring the consumers closer to their deities. Along these lines, Eubulus, who wrote the play “Dionysus”, has Dionysus saying to his patrons:

Three bowls do I mix for the temperate: one to health, which they empty first; the second to love and pleasure; the third to sleep. When this bowl is drunk up, wise guests go home. The fourth bowl is ours no longer, but belongs to violence; the fifth to uproar; the sixth to drunken revel; the seventh to black eyes; the eighth is the policeman’s; the ninth belongs to biliousness; and the tenth to madness and the hurling of furniture [4].

Interestingly, these words of wisdom and warning have held up through the thousands of years since they were first penned.

In China, one of the first alcoholic drinks made from rice, honey and fruit was thought of as a spiritual sustenance rather than a physical one. It was also believed that the moderate use of fermented alcoholic substances was a mandate from heaven and important for inspiration, hospitality and medicinal uses.

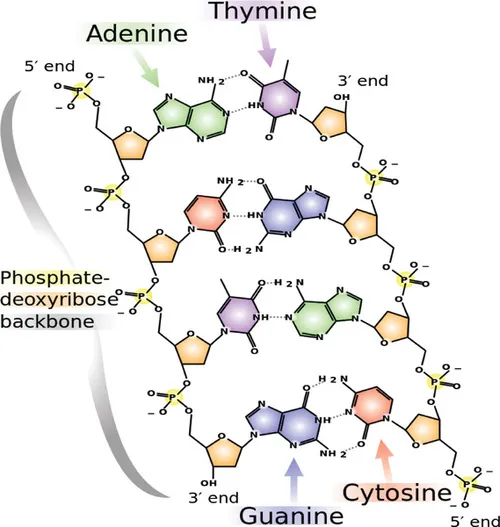

Needless to say, the fermentation of a few carbon sources by different yeast strains has had a profound effect on the world’s societies, culturally and, albeit much later, scientifically. The historical aspect of fermentation will be commented on in this introduction but first we need to look at one of the most important scientific discoveries in modern times, the discovery of the cellular molecule, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). The DNA molecule was first identified and isolated by the Swiss physician and biologist Friedrich Miescher in 1869, with his work being published in 1871 [5]. He had isolated “phosphate rich” molecules from white blood cells, but did not understand the molecules’ significance. This came later when Ludwig Karl Martin Leonhard Albrecht Kossel, a German biochemist and pioneer in the study of genetics, worked out the chemical composition of the DNA molecule. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1910 for this work. Kossel had isolated and described the five organic compounds that are present in nucleic acid: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T) and uracil (U). Eventually these compounds were to become known as nucleobases, the foundation for the formation and structure of DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) in all living cells.

During this same time other scientists were working on determining the structures and chemical nature of these compounds. One of these was the Russian biochemist Phoebus Levene, who published many papers on cellular molecules and is credited with the discovery of the order of the three major components of a nucleotide, the phosphate, the sugar and the base [6]. He also identified the sugar components of both the RNA and DNA molecules as ribose and deoxyribose, respectively. Levene worked extensively with yeast nucleic acids to identify the components and ultimately (in 1919) proposed that the nucleic acids were made up of one distinct base, a sugar and a phosphate molecule (Figure 1.1) [7].

Figure 1.1 Nucleotide bases made up of pyrimidines and purines as well as the addition of the sugar ribose (RNA) or deoxyribose (DNA) and a phosphate group

After nearly 30 years of nucleic acid research, the scientific community received three important contributions. In the 1920s, Frederick Griffith was studying the differences between two Pneumococcal strains (R (non-virulent) and S (virulent)), and while doing so came upon an interesting finding. When he heat-killed the virulent S strain and mixed it with a live non-virulent R strain and then injected this mixture into mice, the mice died of pneumonia. Griffith did not realize it at the time, but he had discovered bacterial transformation through the transfer of DNA to a host bacterium. In 1944, Oswald Avery and his Rockefeller University colleagues published work along these same lines but with a more definitive result. They demonstrated a link between DNA and virulence of these same two strains, by transferring DNA from a heat-killed S strain that was treated with proteases (destroys protein), RNAses (destroys RNA) or DNAses (destroys DNA) to a living non-virulent strain (R strain). What they found was that only R cells, transformed with protease or RNAse treated DNA from the S strain, were shown to be virulent. The DNAse treated mixture did not convert the R cells to a virulent strain.

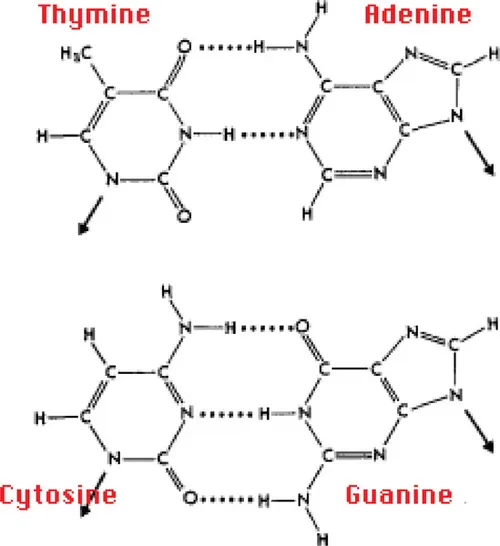

Soon after this work was presented, the Austrian biochemist, Erwin Chargaff, made a startling discovery when he analyzed DNA from different species. He noticed that the nucleotide composition was not the same from one species to the next. He also discovered that within the structure of a DNA molecule, the purines (A and G) and the pyrimidines (C and T) are in equal amounts to the other ([A] = [G] and [C] = [T]). This finding of equality between base pairs is known as “Chargaff’s” rule (Figure 1.2) [8].

Figure 1.2 Chargaff’s rule. In DNA, the total abundance of purines is equal to the total abundance of pyrimidines

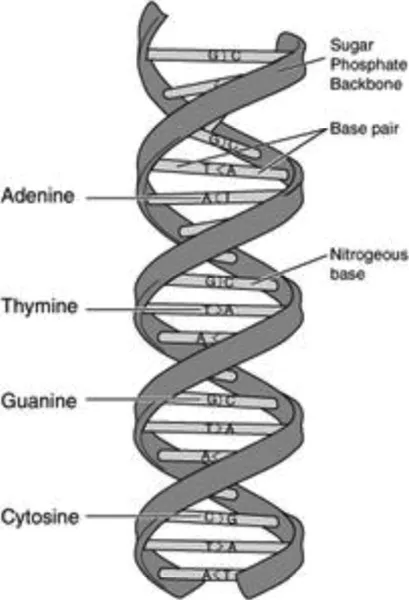

In 1956, James Watson and Francis Crick co-discovered the structure of the DNA and RNA molecules (Figure 1.3). Along with Maurice Wilkins, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. They leaned heavily on the previous findings of Chargaff and his colleagues at the time, as well as having the benefit of the X-ray crystallography work on the DNA molecule done by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. This crucial work led them to define the DNA molecular structure as a double helix [9].

Figure 1.3 Base pairing in DNA is complementary [4]. The purines (A and G) pair with the pyrimidines (T and C, respectively) to form equal-sized base pairs resembling rungs on a ladder (the sugar-phosphate backbones). The ladder twists into a double-helical structure.

1.2 The rise of biotechnology I

1.2.1 The gene

Approximately 20 years after the determination of the structure of the DNA molecule, the term “biotechnology” was established. Wikipedia states that biotechnology is “the application of scientific and engineering principles to the processing of materials by biological agents to provide goods and services”. Biotechnology has its beginnings in what we call zymotechnology, which are the processes/techniques used for the production of beer. Soon after World War I, with the advent of industrial fermentation taking a firm hold on the current larger industrial issues, the path was paved for the increase in scientific research in the area of product formation from the single cell.

By the 1970s, the term “genetic engineering” was becoming commonplace, ironically being used for the first time in Jack Williamson’s science fiction novel Dragon’s Island [10], prior to the connection of DNA as a hereditary molecule and the confirmation of its structure as a double helix. In 1972, the first recombinant DNA molecule was made by combining the DNA from the lamda virus and the SV40 virus. This initial work was done by Paul Berg, which was followed by Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen creating the first transgenic organism by inserting antibiotic resistance genes into a plasmid of E. coli [11].

Before 1983, the name Kary Mullis was little known at best. Dr Mullis was a writer of fiction, a baker, but not a candlestick maker. He was, in fact, a very good biochemist who worked for the Cetus Corporation in California for seven years after his initial wanderings. In this time he worked as a DNA chemist and eventually improved on the already existing polymerase chain reaction (PCR), although improvement is not a strong enough word for the contribution Mullis made to the PCR reaction [11].

A concept similar to that of PCR had be...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright page

- List of figures and tables

- About the author

- 1: Introduction to fermentation

- 2: Generation of a recombinant Escherichia coli expression system

- 3: Recombinant fed-batch fermentation using Escherichia coli

- 4: Escherichia coli produced recombinant protein: Soluble versus insoluble production

- 5: The future of Escherichia coli recombinant fermentation

- References

- Index