- 550 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, Eighth Edition, tackles the biological and environmental influences on behavior as well as the reciprocal interface between changes in the brain and behavior during the course of the adult life span.

The psychology of aging is important to many features of daily life, from workplace and the family, to public policy matters. It is complex, and new questions are continually raised about how behavior changes with age.

Providing perspectives on the behavioral science of aging for diverse disciplines, the handbook explains how the role of behavior is organized and how it changes over time. Along with parallel advances in research methodology, it explicates in great detail patterns and sub-patterns of behavior over the lifespan, and how they are affected by biological, health, and social interactions.

New topics to the eighth edition include preclinical neuropathology, audition and language comprehension in adult aging, cognitive interventions and neural processes, social interrelations, age differences in the connection of mood and cognition, cross-cultural issues, financial decision-making and capacity, technology, gaming, social networking, and more.

- Tackles the biological and environmental influences on behavior as well as the reciprocal interface between changes in the brain and behavior during the course of the adult life span

- Covers the key areas in psychological gerontology research in one volume

- Explains how the role of behavior is organized and how it changes over time

- Completely revised from the previous edition

- New chapter on gender and aging process

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of the Psychology of Aging by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Educational Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Concepts, Theory, Methods

Outline

Chapter 1

Theoretical Perspectives for the Psychology of Aging in a Lifespan Context

K. Warner Schaie, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Most of the editions of the Handbook of the Psychology of Aging have contained a chapter on theoretical issues, some combined with some methodological issues and/or the history of geropsychology. In this introductory chapter some of the major theoretical perspectives in studying normal aging from a lifespan perspective are summarized. This discussion is begun by challenging the often-voiced assumption that pathology is an inevitably aspect of normal aging, and then examples of theories of aging that cover the adult lifespan are described.

Keywords

Normal aging; Lifespan theories of aging; Geropsychology; Pathology

Introduction

Most of the editions of the Handbook of the Psychology of Aging have contained a chapter on theoretical issues, some combined with some methodological issues and/or the history of geropsychology (Baltes & Willis, 1977; Bengtson & Schaie, 1999; Birren & Birren, 1990; Birren & Cunningham, 1985; Birren & Schroots, 1996, 2001; Dixon, 2011; Salthouse, 2006). In this introductory chapter some of the major theoretical perspectives in studying normal aging from a lifespan perspective are summarized. This discussion is begun by challenging the often-voiced assumption that pathology is an inevitably aspect of normal aging and then examples of theories of aging that cover the adult lifespan are described.

The Role of Pathology in Normal Aging

From a lifespan perspective, many of the statements made by psychologists about normal development in the last third of life have been clouded by what can only be described as buying into common societal stereotypes that we now call ageism (Hummert, 2011; Schaie, 1988). Such ageism seems to be informed by the assumption of universal declines in cognitive competence and the development of other undesirable psychological characteristics with advanced age. They have also been informed by clinicians’ experiences in encountering primarily older clients with psychological problems rather than the large number of elderly whom we would describe as aging successfully. In a rapidly changing society we also continue to confuse differences between old and young that are a function of greater educational and other opportunity structures for the younger cohorts with age-related changes. This confusion leads to language in the scientific literature that interprets age differences that reflect complex population differences as “aging decline” (Schaie, 1993).

Assumption of Universal Decline

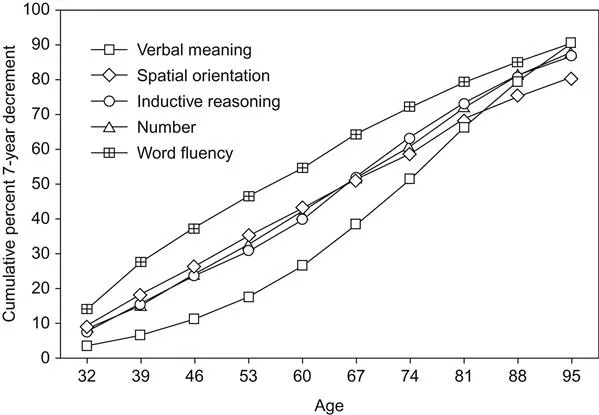

Negative stereotypes about the elderly are ubiquitous with respect to many domains of behavior and perceived attributes (Hess, 2006), even though some exceptions are found in attributed wisdom and altruistic behavior (cf. Pasupathi & Löckenhoff, 2002). Perhaps one of the most serious assumptions made by many psychologists is that of universal cognitive decline. While it is true that the proportion of individuals who show cognitive decline increases with each decade after the 60s are reached, it is equally true that many individuals do not show such decline until close to their demise, and that some fortunate few, in fact, show selective ability gains from midlife into old age. Figure 1.1 shows data from the Seattle Longitudinal Study to document this point (Schaie, 2013).

The data showing that there is no universal decline with increasing age of behavioral effectiveness however should not be interpreted as the absence of biological deficits with increasing age. In fact, disease-free aging is an infrequent experience for only a lucky few (cf. Solomon, 1999). Indeed, effective health behaviors are significantly associated with optimal aging (Aldwin, Spiro, & Park, 2006).

Successful, Normal and Pathological Aging

It is readily apparent that there are vast individual differences in patterns of psychological changes from young adulthood through old age. Scrutiny of a variety of longitudinal studies of psychological aging (cf. Schaie & Hofer, 2001) suggests that four major patterns will describe most of the observed aging trajectories, although further subtypes could, of course, be considered (Schaie, 2008). These patterns would classify individuals into those who age successfully (the super-normals), those who age normally, those who develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and finally those who become clinically diagnosable as suffering from dementia.

The most common pattern is what we could denote as the normal aging of psychological functions. This pattern is characterized by most individuals reaching an asymptote in early midlife, maintaining a plateau until the late 50s or early 60s, and then showing modest decline on most cognitive abilities through the early 80s, with more marked decline in the years prior to death (cf. Bosworth, Schaie, & Willis, 1999). They also tend to become more rigid and show some changes on personality traits in undesirable directions (Schaie, Willis, & Caskie, 2004). Among those whose cognitive aging can be described as normal, we can distinguish two subgroups. The first include those individuals who reach a relatively high level of cognitive functioning who, even if they become physically frail, can remain independent until close to their demise. The second group who only reach a modest asymptote in cognitive development, on the other hand, may in old age require greater support and be more likely to experience a period of institutional care.

A small subgroup of adults experience what is often described as successful aging (Fillit et al., 2002; Rowe & Kahn, 1987). Members of this group are often genetically and socioeconomically advantaged, they tend to continue cognitive development later than most and typically reach their cognitive asymptotes in late midlife. While they too show some very modest decline on highly speeded tasks, they are likely to maintain their overall level of cognitive functioning until shortly before their demise. They are also likely to be less neurotic and more open to experience than most of their age peers. These are the fortunate individuals whose active life expectancy comes very close to their actual life expectancy.

The third pattern, MCI (Petersen et al., 1999), includes that group of individuals who, in early old age, experience greater than normative cognitive declines. Various definitions, mostly statistical, have been advanced to assign membership to this group. Some have argued for a criterion of 1 SD of performance compared to the young adult average, while others have proposed a rating of 0.5 on a clinical dementia rating scale, where 0 is normal and 1.0 is probable dementia. Earlier on, the identification of MCI required the presence of memory loss, in particular. However, more recently the diagnosis has been extended to decline in other cognitive abilities and clinicians now distinguish between amnestic and non-amnestic MCI patterns. There has also been controversy on the question of whether individuals with the diagnosis of MCI inevitably progress to dementia, or whether this group of individuals represents a unique entity; perhaps one that could be denoted as unsuccessful aging (cf. Petersen, 2003).

The final pattern includes those individuals who, in early or advanced old age, are diagnosed as suffering from dementia. Regardless of the specific cause of the dementia these individuals have in common dramatic impairment in cognitive functioning. However, the pattern of cognitive change, particularly in those whose diagnosis at post mortem turns out to be Alzheimer’s disease, is very different from the normally aging. When followed longitudinally, at least some of these individuals show earlier decline, perhaps starting in midlife. But other individuals may have become demented because of increased and sometimes profound vascular brain lesions.

Lifespan Theories of Psychological Aging

There have been few comprehensive theories of psychological development that have fully covered the period of adulthood (Schaie & Willis, 1999). The broadest approaches have been those of Erikson (1982), Erikson, Erikson, and Kivnick (1986), and Baltes (1997). Baltes’ selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) theory represents a dialectical lifespan approach. Psychological gains and losses occur at every life stage, but in old age losses far exceed the gains. Baltes considers evolutionary development incomplete for the very last stage of life, during which societal supports no longer fully compensate for declines in physiological infrastructure and losses in behavioral functionality (see Baltes, 1987; Baltes & Smith, 1999; Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999). SOC, however, can also be seen as strategies of life management, and thus may be indicators of successful aging (Baltes & Freund, 2003). For a fuller exposition of SOC theory and review of relevant empirical studies, see Riedinger, Li, and Lindenberger (2006). The SOC theory has recently been expanded to a co-constructionist biosocial theory (Baltes & Smith, 2004; Willis & Schaie, 2006; see below). Theoretical models limited to the domain of cognition have also been proposed by Schaie and Willis (2000), Willis & Schaie (2006), and Sternberg (1985). I will here describe more fully, the Eriksonian, and the Schaie and Willis stage theories, as well as the more recent co-constructive theory.

Erikson’s Stage Model

Traditional psychodynamic treatments of the lifespan have been restricted primarily to the development of both normal and abnormal personality characteristics. With the exception of some ego psychologists (Loevinger, 1976), however, Erik Erikson remains the primary theorist coming from a psychoanalytic background who has consistently pursued a lifespan approach. Although Erikson’s most famous concept, the identity crisis, is placed in adolescence, the turmoil of deciding “who you are” continues in adulthood, and identity crises often recur throughout life, even in old age (Erikson, 1979). Moreover, Erikson (1982) takes the position that “human development is dominated by dramatic shifts in emphasis.”

In his latest writing, Erikson (influenced by his wife Joan) redistributed the emphasis on the various life stages more equitably. He argued that the question of greatest priority in the study of ego development is “how, on the basis of a unique life cycle and a unique complex of psychosocial dynamics, each individual struggles to reconcile earlier themes in order to bring into balance a lifelong sense of trustworthy wholeness and an opposing sense of bleak fragmentation” (Davidson, 1995; Erikson et al., 1986; Goleman, 1988).

The intimacy crisis is the primary psychosocial issue in the young adult’s thoughts and feelings about marriage and family. However, recent writers suggest that this crisis must be preceded by identity consolidation that is also thought to occur in young adulthood (cf. Pals, 1999).

The primary issue of middle age, according to Erikson, is generativity versus stagnation (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1998; Snarey, Son, Kuehne, Hauser, & Vaillant, 1987). Broadly conceived, generativity includes the education of one’s children, productivity and creativity in one’s work, and a continuing revitalization of one’s spirit that allows for fresh and active participation in all facets of life. Manifestations of the generativity crisis in midlife are career problems, marital difficulties, and widely scattered attempts at “self-improvement.”

Successful resolution of the generativi...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Concepts, Theory, Methods

- Part II: Bio-psychosocial Factors in Aging

- Part III: Behavioral Processes

- Part IV: Complex Processes

- Author Index

- Subject Index