- 492 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Deep Shale Oil and Gas

About this book

Natural gas and crude oil production from hydrocarbon rich deep shale formations is one of the most quickly expanding trends in domestic oil and gas exploration. Vast new natural gas and oil resources are being discovered every year across North America and one of those new resources comes from the development of deep shale formations, typically located many thousands of feet below the surface of the Earth in tight, low permeability formations. Deep Shale Oil and Gas provides an introduction to shale gas resources as well as offer a basic understanding of the geomechanical properties of shale, the need for hydraulic fracturing, and an indication of shale gas processing. The book also examines the issues regarding the nature of shale gas development, the potential environmental impacts, and the ability of the current regulatory structure to deal with these issues. Deep Shale Oil and Gas delivers a useful reference that today's petroleum and natural gas engineer can use to make informed decisions about meeting and managing the challenges they may face in the development of these resources.

- Clarifies all the basic information needed to quickly understand today's deeper shale oil and gas industry, horizontal drilling, fracture fluids chemicals needed, and completions

- Addresses critical coverage on water treatment in shale, and important and evolving technology

- Practical handbook with real-world case shale plays discussed, especially the up-and-coming deeper areas of shale development

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Deep Shale Oil and Gas by James G. Speight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Natural Resource Extraction Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Gas and Oil in Tight Formations

Abstract

Natural gas and crude oil from shale and tight formations offer additional energy-producing resources that can be recovered from shale formations that typically function as both the reservoir rock and the source rock. In terms of chemical makeup, shale gas is typically a dry gas composed primarily of methane but some formations do produce wet gas while crude oil from tight formations is typically more volatile than many crude oils from conventional reservoirs. The shale formations that yield gas and oil are organic-rich shale formations that were previously regarded only as source rocks and seals for gas accumulating in the strata near sandstone and carbonate reservoirs of traditional onshore gas development. On the other hand, the crude oil from shale formations is a light highly volatile crude oil that contains more of the volatile hydrocarbons (C1–C4) than many conventional crude oils. In addition, the gas and oil storage properties of shale are quite different to conventional reservoirs. In the case of shale formations, the natural gas and crude oil present in the matrix system of pores—similar to that found in conventional reservoir rocks—are accompanied by gas or oil that is bound to, or adsorbed on, the surface of inorganic minerals in the shale. The relative contributions and combinations of free gas and oil from matrix porosity and from desorption of adsorbed constituents is a key determinant of the production profile of the well.

It is the purpose of this chapter to introduce the reader to the definitions and terminology used in the area of natural gas and crude oil from shale reservoirs.

Keywords

Origin; Shale; Shale reservoirs; Conventional gas; Unconventional gas; Natural gas; Coalbed methane; Energy security; Tight gas; Tight sands

1 Introduction

The generic terms crude oil (also referred to as petroleum) and natural gas apply to the mixture of liquids and gases, respectively, commonly associated with petroliferous (petroleum-producing, petroleum-containing) geologic formations (Speight, 2014a) and which has been extended to gases and liquids from the recently developed deep shale formations (Speight, 2013b).

Crude oil and natural gas are the most important raw materials consumed in modern society—they provide raw materials for the ubiquitous plastics and other products as well as fuels for energy, industry, heating, and transportation. From a chemical standpoint, natural gas and crude oil are a mixture of hydrocarbon compounds and nonhydrocarbon compounds with crude oil being much more complex than natural gas (Mokhatab et al., 2006; Speight, 2007, 2012a, 2014a). The fuels that are derived from these two natural products supply more than half of the world's total supply of energy. Gas (for gas burners and for the manufacture of petrochemicals), gasoline, kerosene, and diesel oil provide fuel for automobiles, tractors, trucks, aircraft, and ships (Speight, 2014a). In addition, fuel oil and natural gas are used to heat homes and commercial buildings, as well as to generate electricity.

Crude oil and natural gas are carbon-based resources. Therefore, the geochemical carbon cycle is also of interest to fossil fuel usage in terms of petroleum formation, use, and the buildup of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Thus, the more efficient use of natural gas and crude oil is of paramount importance and the technology involved in processing both feedstocks will supply the industrialized nations of the world for (at least) the next 50 years until suitable alternative forms of energy are readily available (Boyle, 1996; Ramage, 1997; Speight, 2011a,b,c).

In this context, it is relevant to introduce the term peak oil which refers to the maximum rate of oil production, after which the rate of production of this natural resources (in fact the rate of production of any natural resource) enters a terminal decline (Hubbert, 1956, 1962). Peak oil production usually occurs after approximately half of the recoverable oil in an oil reserve has been produced (i.e., extracted). Peaking means that the rate of world oil production cannot increase and that oil production will thereafter decrease with time; even if the demand for oil remains the same or increases. Following from this, the term peak energy is the point in time after which energy production declines and the production of energy from various energy sources is in decline. In fact, most oil-producing countries—including Indonesia, the United Kingdom, Norway, and the United States—have passed the peak crude oil production apex several years or decades ago. Their production declines have been offset by discoveries and production growth elsewhere in the world and the so-called peak energy precipice will be delayed by such discoveries as well as by further development or crude oil and natural gas resources that are held in tight formations and tight shale formations (Islam and Speight, 2016).

However, before progressing any further, a series of definitions are used to explain the terminology used in this book.

2 Definitions

The definitions of crude oil and natural gas have been varied and diverse and are the product of many years of the growth of the crude oil and natural gas processing industries. Of the many forms of the definitions that have been used not all have survived but the more common, as illustrated here, are used in this book. Also included for comparison are sources of gas—such as gas hydrates and other sources of gas—that will present an indication of future sources of gaseous energy.

2.1 Crude Oil

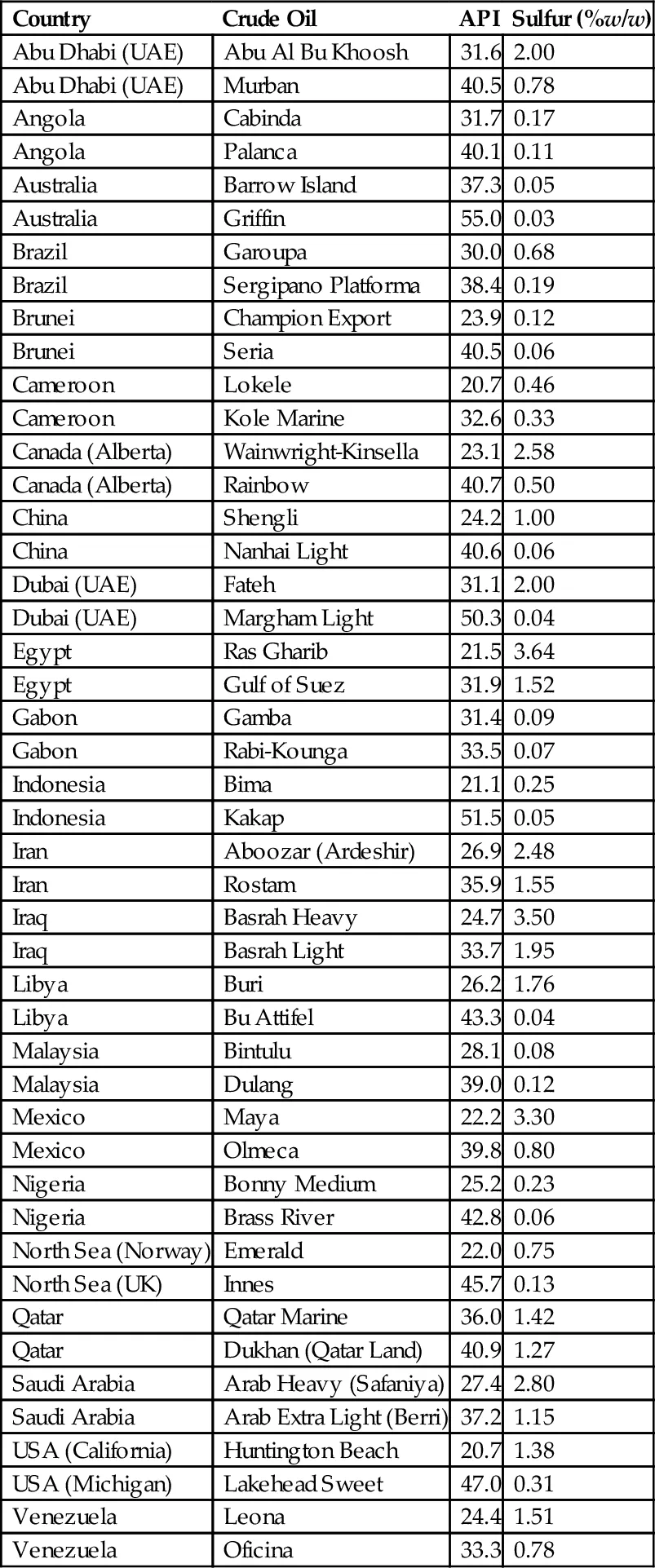

The term crude oil (and the equivalent term petroleum) covers a wide assortment of naturally occurring hydrocarbon-type liquids consisting of mixtures of hydrocarbons and nonhydrocarbon compounds containing variable amounts of sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen as well as heavy metals such as nickel and vanadium, which may vary widely in volatility, specific gravity, and viscosity along with varying physical properties such as API gravity and sulfur content (Tables 1.1 and 1.2) as well as being accompanied by variations in color that ranges from colorless to black—the lower API gravity crude oils are darker than the higher API gravity crude oils (Speight, 2012a, 2014a; US EIA, 2014). The metal-containing constituents, notably those compounds consisting of derivatives of vanadium and nickel with, on occasion iron and copper, usually occur in the more viscous crude oils in amounts up to several thousand parts per million and can have serious consequences for the equipment and catalysts used in processing of these feedstocks (Speight and Ozum, 2002; Parkash, 2003; Hsu and Robinson, 2006; Gary et al., 2007; Speight, 2014a). The presence of iron and copper has been subject to much speculation insofar as it is not clear if these two metals are naturally occurring in the crude oil or whether they are absorbed by the crude oil during recovery and transportation in metal pipelines.

Table 1.1

Selected Crude Oils Showing the Differences in API Gravity and Sulfur Content

| Country | Crude Oil | API | Sulfur (%w/w) |

| Abu Dhabi (UAE) | Abu Al Bu Khoosh | 31.6 | 2.00 |

| Abu Dhabi (UAE) | Murban | 40.5 | 0.78 |

| Angola | Cabinda | 31.7 | 0.17 |

| Angola | Palanca | 40.1 | 0.11 |

| Australia | Barrow Island | 37.3 | 0.05 |

| Australia | Griffin | 55.0 | 0.03 |

| Brazil | Garoupa | 30.0 | 0.68 |

| Brazil | Sergipano Platforma | 38.4 | 0.19 |

| Brunei | Champion Export | 23.9 | 0.12 |

| Brunei | Seria | 40.5 | 0.06 |

| Cameroon | Lokele | 20.7 | 0.46 |

| Cameroon | Kole Marine | 32.6 | 0.33 |

| Canada (Alberta) | Wainwright-Kinsella | 23.1 | 2.58 |

| Canada (Alberta) | Rainbow | 40.7 | 0.50 |

| China | Shengli | 24.2 | 1.00 |

| China | Nanhai Light | 40.6 | 0.06 |

| Dubai (UAE) | Fateh | 31.1 | 2.00 |

| Dubai (UAE) | Margham Light | 50.3 | 0.04 |

| Egypt | Ras Gharib | 21.5 | 3.64 |

| Egypt | Gulf of Suez | 31.9 | 1.52 |

| Gabon | Gamba | 31.4 | 0.09 |

| Gabon | Rabi-Kounga | 33.5 | 0.07 |

| Indonesia | Bima | 21.1 | 0.25 |

| Indonesia | Kakap | 51.5 | 0.05 |

| Iran | Aboozar (Ardeshir) | 26.9 | 2.48 |

| Iran | Rostam | 35.9 | 1.55 |

| Iraq | Basrah Heavy | 24.7 | 3.50 |

| Iraq | Basrah Light | 33.7 | 1.95 |

| Libya | Buri | 26.2 | 1.76 |

| Libya | Bu Attifel | 43.3 | 0.04 |

| Malaysia | Bintulu | 28.1 | 0.08 |

| Malaysia | Dulang | 39.0 | 0.12 |

| Mexico | Maya | 22.2 | 3.30 |

| Mexico | Olmeca | 39.8 | 0.80 |

| Nigeria | Bonny Medium | 25.2 | 0.23 |

| Nigeria | Brass River | 42.8 | 0.06 |

| North Sea (Norway) | Emerald | 22.0 | 0.75 |

| North Sea (UK) | Innes | 45.7 | 0.13 |

| Qatar | Qatar Marine | 36.0 | 1.42 |

| Qatar | Dukhan (Qatar Land) | 40.9 | 1.27 |

| Saudi Arabia | Arab Heavy (Safaniya) | 27.4 | 2.80 |

| Saudi Arabia | Arab Extra Light (Berri) | 37.2 | 1.15 |

| USA (California) | Huntington Beach | 20.7 | 1.38 |

| USA (Michigan) | Lakehead Sweet | 47.0 | 0.31 |

| Venezuela | Leona | 24.4 | 1.51 |

| Venezuela | Oficina | 33.3 | 0.78 |

Table 1.2

API Gravity and Sulfur Content of Selected Heavy Oils

| Country | Crud... |

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- About the Author

- Preface

- Chapter One: Gas and Oil in Tight Formations

- Chapter Two: Reservoirs and Reservoir Fluids

- Chapter Three: Gas and Oil Resources in Tight Formations

- Chapter Four: Development and Production

- Chapter Five: Hydraulic Fracturing

- Chapter Six: Fluids Management

- Chapter Seven: Properties Processing of Gas From Tight Formations

- Chapter Eight: Properties and Processing of Crude Oil From Tight Formations

- Chapter Nine: Environmental Impact

- Conversion Factors

- Glossary

- Index