- 386 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis

About this book

Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis is a comprehensive reference that not only synthesizes the current literature but also offers practical protocols that industrial and academic scientists can immediately put to use in their daily work. Increasing interest in green chemistry has led to the development of numerous environmentally-friendly methodologies for the synthesis of organic molecules of interest. Amongst the green methodologies drawing attention, mechanochemistry is emerging as a promising method to circumvent the use of toxic solvents and reagents as well as to increase energy efficiency.The development of synthetic strategies that require less, or the minimal, amount of energy to carry out a specific reaction with optimum productivity is of vital importance for large-scale industrial production. Experimental procedures at room temperature are the mildest reaction conditions (essentially required for many temperature-sensitive organic substrates as a key step in multi-step sequence reactions) and are the core of mechanochemical organic synthesis. This green synthetic method is now emerging in a very progressive manner and until now, there is no book that reviews the recent developments in this area.- Features cutting-edge research in the field of mechanochemical organic synthesis for more sustainable reactions- Integrates advances in green chemistry research into industrial applications and process development- Focuses on designing techniques in organic synthesis directed toward mild reaction conditions- Includes global coverage of mechanochemical synthetic protocols for the generation of organic compounds

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Practical Considerations in Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis

Abstract

Keywords

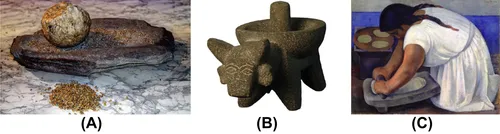

Ball mill; Contamination from wear; Ex situ and in situ reaction monitoring; Mechanochemistry; Milling parameters; Organic synthesis; Solid-state analysis1.1. A Historical Perspective

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Chapter 1. Practical Considerations in Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis

- Chapter 2. Carbon–Carbon Bond- Forming Reactions

- Chapter 3. Carbon–Nitrogen Bond-Formation Reactions

- Chapter 4. Carbon—Oxygen and Other Bond-Formation Reactions

- Chapter 5. Cycloaddition Reactions

- Chapter 6. Oxidations and Reductions

- Chapter 7. Applications of Ball Milling in Nanocarbon Material Synthesis

- Chapter 8. Applications of Ball Milling in Supramolecular Chemistry

- Chapter 9. Experiments for Introduction of Mechanochemistry in the Undergraduate Curriculum

- Author Index

- Subject Index