eBook - ePub

Forest Plans of North America

- 482 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forest Plans of North America

About this book

Forest Plans of North America presents case studies of contemporary forest management plans developed for forests owned by federal, state, county, and municipal governments, communities, families, individuals, industry, investment organizations, conservation organizations, and others in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The book provides excellent real-life examples of contemporary forest planning processes, the various methods used, and the diversity of objectives and constraints faced by forest owners.

Chapters are written by those who have developed the plans, with each contribution following a unified format and allowing a common, clear presentation of the material, along with consistent treatment of various aspects of the plans. This work complements other books published by members of the same editorial team (Forest Management and Planning, Introduction to Forestry and Natural Resource Management), which describe the planning process and the various methods one might use to develop a plan, but in general do not, as this work does, illustrate what has specifically been developed by landowners and land managers. This is an in-depth compilation of case studies on the development of forest management plans by the different landowner groups in North America.

The book offers students, practitioners, policy makers, and the general public an opportunity to greatly improve their appreciation of forest management and, more importantly, foster an understanding of why our forests today are what they are and what forces and tools may shape their tomorrow. Forest Plans of North America provides a solid supplement to those texts that are used as learning tools for forest management courses. In addition, the work functions as a reference for the types of processes used and issues addressed in the early 21st century for managing land resources.

- Presents 40-50 case studies of forest plans developed for a wide variety of organizations, groups, and landowners in North America

- Illustrates plans that have specifically been developed by landowners and land managers

- Features engaging, clearly written content that is accessible rather than highly technical, while demonstrating the issues and methods involved in the development of the plans

- Each chapter contains color photographs, maps, and figures

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forest Plans of North America by Jacek P. Siry,Pete Bettinger,Krista Merry,Donald L. Grebner,Kevin Boston,Chris Cieszewski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco, New Jersey, United States of America

Steven W. Kallesser Gracie & Harrigan Consulting Foresters, Inc., Far Hills, New Jersey, USA

Absract

Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco is a 381-acre Boy Scout camp located in the northwestern portion of New Jersey that exhibits many of the planning opportunities characteristic of small, low-intensity private forest landowners and private recreation areas. Through proper forest planning, consulting foresters have been able to improve the owner’s ability to deliver its program at the camp, address issues endemic to highly stocked mid-successional oak forests, and improve biodiversity. This case study examines the role of conservation planning within the Boy Scout organization as it pertains to individual camps, challenges of working for charitable not-for-profit corporations, and the role that foresters can play with smaller landowners particularly in a state or area lacking a robust forest products industry.

Keywords

Forest planning

Recreation

Small low-intensity private forest

Golden-winged warbler

Boy Scouts of America

Abbreviations

BSA Boy Scouts of America

DEP Department of Environmental Protection

EQIP Environmental Quality Incentives Program

NJ New Jersey

NJSA New Jersey Statutes Annotated

WLFW Working Lands for Wildlife

Management Setting and Background

Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco is the oldest continuously operating Boy Scout summer camp in the state of New Jersey (Jenkins, 2012). It is currently owned and operated by the Northern New Jersey Council, Boy Scouts of America (hereafter “the Council”), having been purchased by a predecessor entity in several transactions in 1928 and 1930. The property is currently understood to be 380.8 acres (ac) (154.1 hectares (ha)), of which 342.9 ac (138.8 ha) are woodland, with 17.3 ac (7.0 ha) of pond, 12.7 ac (5.1 ha) under an electrical transmission right-of-way, and 7.9 ac (3.2 ha) being non-forested camp facility areas.

The camp is located within the Ridge and Valley geologic province of northwest New Jersey and at the foot of the Kittatinny Ridge. The camp has an extensive history of past management. The forest was likely within seasonal hunting routes of the Minisink subgroup of the Delaware tribe, given its close proximity to known villages along the Delaware River and proximity to an important gap in the Kittatinny Ridge. As such, the forest would have had a history of low- and moderate-intensity wildfires as part of its hunting regimen. Four or five early homesites were located on the property, with two of these being associated with very small sustenance farms. These farms were abandoned prior to 1878. Aside from a minor amount of land clearing associated with the activities and from wood extracted for fuel and farm buildings, very little history of management is apparent until about 1854. At that time, the railroad was extended to Newton, the nearby seat of Sussex County. At about that time, demand was ramping up for fuel for iron furnaces and other industrial developments. The extensive forests of the Ridge and Valley and Highlands provided this fuel and other valuable wood products. By 1874, three sawmills were located within one-half mile of the camp boundary. One of those sawmill owners had title to most of the property and owned a second sawmill on the Paulins Kill that made axe handles. One of the old farmsteads has evidence of being used as a logging camp, likely during the 1880s. In the 1910s or early 1920s, the property was likely heavily cut for charcoal production. The forest is currently composed of mature hardwood trees, the vast majority of which are about 90 to 95 years old. This relatively recent history is confirmed through the earliest photographs and postcards of the camp showing mostly saplings with occasional larger trees of poor growth form.

In the summer of 1927, the camp was leased from a contract purchaser. At that point, campsites were cleared, trails were built, and a dining hall was constructed mostly from American chestnut (Castanea dentata) salvage. The title to the land was obtained by the Boy Scouts from the contract purchaser in 1928 and, with some additional land purchases, totaled about 980 ac (396.6 ha) in 1930. The Council continued to construct log cabins from chestnut logs until 1931 when it was forced to lay off its camp ranger. By 1942, the Council had begun to barter timber with local sawmills in exchange for dimensional lumber and other wood products in order to build cabins, lean-tos, and other buildings throughout the camp. Such records of annual forestry reports exist through 1967. Following this period, there appears to have been several individual tree selection harvests, the last of which was primarily a salvage of trees in 1989 due to a gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) outbreak. Generally speaking, the Council appears to have obtained informal advice from government agents during most of this time. The Council’s promotional material routinely touted the involvement of persons from the NJ Department of Conservation, the USDA Soil Conservation Service, as well as a wide variety of educators, academics, and people from the conservation not-for-profit community.

The forest at the camp was first assessed by Gracie & Harrigan Consulting Foresters, Inc. in 1999 during a forest inventory in advance of a forest management plan that was written in 2000. The 2000 Plan was most likely the first written forestry plan for the camp. The reason for developing a plan for the property at that time involved an effort to reduce the property taxes for the Council. In accordance with the Farmland Assessment Act of 1964, as amended (NJSA 54:4-23.1 et seq.), a property may qualify for assessment based on an agricultural valuation if the property is able to meet certain agricultural activity and income tests annually. Wood products are considered agricultural in nature. However, for properties that are principally forested, a “woodland management plan” must be prepared and approved by a forester who therein is approved to practice forestry by the NJ Department of Environmental Protection Forest Service. A forester must also annually attest to the fact that the landowner is adhering to the recommendations in the plan.

At the time of the preparation of the 2000 Plan, mapping problems became apparent to the Council and its consulting foresters. Although the camp had been surveyed at the time of its purchase, and portions of the camp were resurveyed in 1965, no unified map existed. To complicate matters, in 1970 the federal government condemned nearly 600 ac (242.81 ha) of the camp property to be used for the Tocks Island dam project (now known as the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area). What had existed in terms of maps were never updated, and the Council’s internal maps from that point on apparently relied on amateurish deed plots and municipal tax maps. Given the unclear boundary, forest management activities were focused initially on areas well within the camp boundaries.

Forestry activities during the term of the 2000 Plan focused on projects that could be implemented by volunteers, or by contractors who were compensated through federal cost-share programs such as the Forest Land Enhancement Program, the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program, and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program. Examples of these activities included 15 ac (6.1 ha) of precommercial thinning, 26 ac (10.5 ha) of non-native invasive plant control, 2 ac (0.8 ha) where seedlings of various tree and shrubs were underplanted, and 1.25 ac (0.5 ha) in a group selection harvest system. In addition, 300 ac (121.4 ha) of the upland forest were sprayed to control gypsy moths during two successive growing seasons. Access throughout the property was improved, and intense research on resolving boundary issues was conducted, concluding with a definitive remarking of boundary lines in 2006. Unfortunately for wildlife species requiring elements of young forests, the limited age distribution of Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco is characteristic of upland forests within heavily forested areas of the Ridge and Valley and northern Highlands provinces within northern New Jersey.

Just as important to the Council were educational materials made available to scouts and scoutmasters. These were improved following the 2000 Plan. A permanent self-guided ecology and forestry interpretive trail was established in 2006. This trail identifies and interprets various forestry practices on the property and other important ecological features. Also, the Council and the consulting foresters maintain a set of “From the Forester” fact sheets that are designed to explain potentially difficult topics to merit-badge instructors and to guide them to useful areas within camp to teach on the topic.

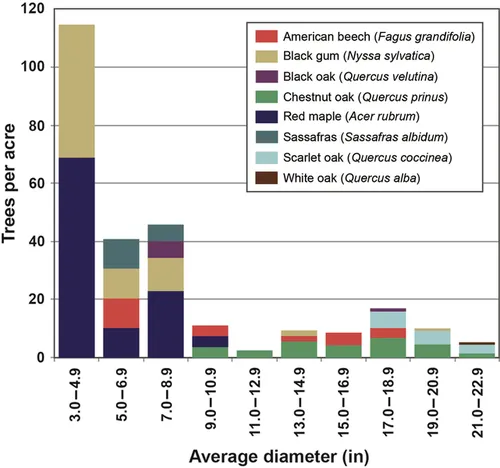

The forest was re-inventoried in 2010 to prepare for the development of the management plan. The Council opted to have a Forest Stewardship Plan developed in order to pursue cost-sharing assistance for plan development through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. At the time of the 2010 inventory, 342.9 ac (138.8 ha) of forest were identified, of which 47.2 ac (19.1 ha) are wetlands or are immediately adjacent to wetlands. Most of these lowland areas are extremely mucky and are currently impacted by beavers. Of the remaining 295.7 ac (119.7 ha), 99.6% are mid-successional, mostly having years of origin of between 1900 and 1925. Most of the upland forest is oak-hickory (76%) (Figure 1.1), with some mesic areas dominated by yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) (24%). Areas unthinned during the 2000 Plan were at high levels of full stocking, with relative densities of 84% to 100%. Other areas that had been thinned, had experienced high mortality during the 1987–1989 gypsy moth infestations, or had experienced mortality from hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), were at lower levels of full stocking with relative densities ranging from 63% to 70%. The forests are generally considered two-aged. A typical age class and species distribution of the upland forests is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.1 Hardwood forests typical of the Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco property. Photograph courtesy of William Kallesser.

Figure 1.2 A typical two-aged distribution of the upland forests of the Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco property.

Planning Environment and Methodology

Local councils of the Boy Scouts of America are organized to serve youth within a defined geographic area. The Council is governed by a board of directors. The directors, some of whom are officers, are elected annually by representatives of institutions that sponsor scouting units (e.g., Boy Scout troops, Cub Scout packs, etc.), directors, and members-at-large. The board establishes certain standing committees whose members include directors and other volunteers. These committees are often composed of various subcommittees with more specific purposes. Each Council’s board of directors also hires a scout executive who functions as the chief executive officer. The scout executive manages a professional staff whose responsibilities are to serve as professional advisors to the various committees and ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Units

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1: Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco, New Jersey, United States of America

- Chapter 2: Eddyville Tree Farm, Oregon, United States of America

- Chapter 3: Michael Family Forest, Texas, United States of America

- Chapter 4: Pike Lumber Company’s Sam Little Forest, Indiana, United States of America

- Chapter 5: Poole and Pianta Woodlot, West Virginia, United States of America

- Chapter 6: Rib Lake School Forest, Wisconsin, United States of America

- Chapter 7: Shirley Town Forest, New Hampshire, United States of America

- Chapter 8: Arcata Community Forest, California, United States of America

- Chapter 9: Ejido Borbollones, Durango, Mexico

- Chapter 10: Harvard University Forest, Massachusetts, United States of America

- Chapter 11: Dubuar Memorial Forest, New York, United States of America

- Chapter 12: McPhail Tree Farm, South Carolina, United States of America

- Chapter 13: Molinillos Private Forest Estate, Durango, Mexico

- Chapter 14: Ross Forests, Tennessee, United States of America

- Chapter 15: Willow Break LLC, Mississippi, United States of America

- Chapter 16: Blue Ridge Parkway, Virginia and North Carolina, United States of America

- Chapter 17: Chesapeake Forest Lands, Maryland, United States of America

- Chapter 18: Durango State University Forest Las Bayas, Durango, Mexico

- Chapter 19: Garcia River Forest, California, United States of America

- Chapter 20: Indigenous Community of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacán, Mexico

- Chapter 21: Jackson Demonstration State Forest, California, United States of America

- Chapter 22: Mission Municipal Forest, British Columbia, Canada

- Chapter 23: San Pedro El Alto Community Forest, Oaxaca, Mexico

- Chapter 24: Sand Hills State Forest, South Carolina, United States of America

- Chapter 25: Sessoms Timber Trust, Georgia, United States of America

- Chapter 26: South Willapa Bay Conservation Area, Washington, United States of America

- Chapter 27: Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge, New Hampshire, United States of America

- Chapter 28: Weaverville Community Forest, California, United States of America

- Chapter 29: Yale School Forests, New England, United States of America

- Chapter 30: Bayfield County Forest, Wisconsin, United States of America

- Chapter 31: Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest, Georgia, United States of America

- Chapter 32: City of San Francisco, California, United States of America

- Chapter 33: Forest Management Unit 13—Forest Management License (FMU) 3, Manitoba, Canada

- Chapter 34: Fort Wainwright, Alaska, United States of America

- Chapter 35: Green Diamond Resource Company, California, United States of America

- Chapter 36: Northwest Oregon State Forests, United States of America

- Chapter 37: Revelstoke Community Forest—Tree Farm License (TFL) 56, British Columbia, Canada

- Chapter 38: South Puget Planning Unit, Washington, United States of America

- Chapter 39: Weyerhaeuser, North Carolina, United States of America

- Chapter 40: Yakama Reservation, Washington, United States of America

- Chapter 41: French-Severn Forest, Ontario, Canada

- Chapter 42: Martel Forest, Ontario, Canada

- Chapter 43: Prince Albert Forest Management Agreement (FMA), Saskatchewan, Canada

- Chapter 44: Rayonier, Inc., Southern United States of America

- Chapter 45: San Juan National Forest, Colorado, United States of America

- Chapter 46: Tongass National Forest, Alaska, United States of America

- Chapter 47: Western Oregon Districts, Bureau of Land Management, United States of America

- Chapter 48: Whitefeather Forest, Ontario, Canada

- Chapter 49: Synopsis of Forest Management Plans of North America

- Index