- 758 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Biological Research on Addiction examines the neurobiological mechanisms of drug use and drug addiction, describing how the brain responds to addictive substances as well as how it is affected by drugs of abuse. The book's four main sections examine behavioral and molecular biology; neuroscience; genetics; and neuroimaging and neuropharmacology as they relate to the addictive process.

This volume is especially effective in presenting current knowledge on the key neurobiological and genetic elements in an individual's susceptibility to drug dependence, as well as the processes by which some individuals proceed from casual drug use to drug dependence.

Biological Research on Addiction is one of three volumes comprising the 2,500-page series, Comprehensive Addictive Behaviors and Disorders. This series provides the most complete collection of current knowledge on addictive behaviors and disorders to date. In short, it is the definitive reference work on addictions.

- Each article provides glossary, full references, suggested readings, and a list of web resources

- Edited and authored by the leaders in the field around the globe – the broadest, most expert coverage available

- Discusses the genetic basis of addiction

- Covers basic science research from a variety of animal studies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biological Research on Addiction by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Adicción en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section II

Neuroscience

Chapter 17 Common Mechanisms of Addiction

Chapter 18 Neuroadaptive Changes that Result from Chronic Drug Exposure

Chapter 19 The Dark Side of Addiction

Chapter 20 Integrating Body and Brain Systems in Addiction Neuroscience

Chapter 21 Brain Sites and Neurotransmitter Systems Mediating the Reinforcing Effects of Alcohol

Chapter 22 The Mesolimbic Dopamine Reward System and Drug Addiction

Chapter 23 Molecular and Functional Changes in Receptors

Chapter 24 Serotonin and Behavioral Stimulant Effects of Addictive Drugs

Chapter 25 The Role of Glutamate Receptors in Addiction

Chapter 26 Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Addiction

Chapter 27 Common Molecular Mechanisms and Neurocircuitry in Alcohol and Nicotine Addiction

Chapter 28 The Role of Brain Development in Drug Effect and Drug Response

Chapter 29 Molecular Targets of Ethanol in the Developing Brain

Chapter 30 Addiction, Hippocampal Neurogenesis, and Neuroplasticity in the Adult Brain

Chapter 31 Neurogenesis and Addictive Disorders

Chapter 32 Neural Mechanisms of Learning

Chapter 33 Memory Reconsolidation and Drugs of Abuse

Chapter 34 Binge Drinking and Withdrawal

Chapter 35 The Neural Basis of Decision Making in Addiction

Chapter 36 Addiction and the Human Adolescent Brain

Chapter 37 Neuropsychological Precursors and Consequences of Addiction

Chapter 38 Human Neurophysiology

Chapter 39 Incentive Salience and the Transition to Addiction

Chapter 40 The Neurobiological Basis of Personality Risk for Addiction

Chapter 41 Neuroeconomics and Addiction

Chapter 42 Common Neural Mechanisms in Obesity and Drug Addiction

Chapter 43 Brain Mechanisms of Addiction Treatment Effects

Chapter 44 Genetics of Ecstasy (MDMA) Use

Chapter 45 Genetics of Nicotine Addiction

Chapter 17

Common Mechanisms of Addiction

Kathryn J. Reissner and Peter W. Kalivas, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Outline

Introduction

Risk Factors

Relapse Vulnerability: Stress, Context, and Drug Cues

Neurocircuitry of Addiction

Decision-making and Cognitive Control

Cellular Correlates

Dopaminergic Signaling

Glutamatergic Signaling

Conclusions

Introduction

The enduring effects of drugs of abuse that are associated with addiction manifest in many ways, including changes in behavior, metabolic brain activity, and cell signaling and physiology. The most readily observable adverse consequences of addiction are the behavioral manifestations of the disease, e.g. loss of employment, relationships, and medical health. The pursuit of drug use despite these consequences represents a major factor in the diagnosis of addiction and is common among all major drugs of abuse. Research into the neurobiology of addiction over the last decade has also illuminated enduring cellular changes induced by drugs of abuse that are thought to provide neural substrates for the behavioral pathologies. Importantly, these cellular changes provide avenues for development of candidate pharmacotherapies for addiction that can supplement and support behavioral modification therapies. However, an important question is to what degree are the enduring cellular changes induced by drugs of abuse similar or different across all classes of drugs? Further, are changes similar when a single drug is abused, compared with multiple drugs of different classes? Identifying these similarities and differences provides insight not only into mechanisms of addiction but also into the merit of candidate pharmacotherapies for addiction. In this chapter, we will assess commonalities among risk factors for addiction, as well as among enduring changes induced by drugs of abuse. These commonalities extend across all levels of analysis, from personality traits, to decision-making ability and cognitive control, to gene expression and other cellular changes associated with addiction to different classes of abused drugs.

As addressed in chapters throughout this edition, addiction may range from substance abuse to gambling, food, internet, sex, and other behaviors. However, unless specified otherwise, all discussion in this chapter will focus on addiction to drugs of abuse; nonetheless, ongoing research will continue to elucidate whether the anatomical and cellular substrates of addiction to drugs of abuse may or may not generalize to other addictions as well.

Risk Factors

Because the development of an addictive disorder occurs in stages bridging social use to compulsive abuse, it is of interest to identify risk factors that influence the transition from casual use to abuse and addiction. Risk factors for addiction may be identified as specific genetic loci or as behavioral traits (endophenotypes) conferring vulnerability to addiction. While research focused on genetic risk factors for addiction can yield important clues, this field remains in a relatively early stage. To date, particular progress has been made in identification of genetic polymorphisms for alcohol and nicotine abuse. For example, polymorphisms in genes responsible for metabolism of alcohol are associated with increased risk of dependence; however, this increased risk appears to be alcohol specific. Genetic variants in chromosomal regions encoding multiple acetylcholine receptor subunits are associated with increased risk of nicotine dependence. In particular, a variant in the α5 acetylcholine receptor subunit that confers increased risk toward nicotine dependence has also been correlated with a paradoxical decreased risk of alcohol and cocaine dependence. Despite the complicated nature of identification of specific genetic risk factors for substance abuse disorders, the heritability of generalized addiction is clear. Numerous family and twin studies have illustrated predisposition to dependence regardless of substance type. Further discussion of these points can be found in the review by Bierut, recommended in the section for further reading.

Beyond genetic variants that encode for increased vulnerability or protection from addiction, behavioral endophenotypes have also emerged as elements that may confer a more generalized addiction risk. In particular, impulsivity has been identified as a risk factor for development of a substance abuse disorder as well as compulsive relapse following abstinence. This observation is supported by findings in the clinical treatment of human addicts, as well as in preclinical animal models of addiction. Increased measure of impulsive behavior has been associated with cocaine, amphetamine, nicotine, and alcohol abuse, as well as other addiction disorders including gambling and internet use. Interestingly, existing evidence indicates that impulsivity may reflect greater propensity toward psychostimulant dependence (e.g. rather than heroin and other opiates), although further studies are required to validate this observation. Moreover, it is critical to distinguish trait impulsivity as a risk factor for addiction from the development of use-dependent impulsivity (discussed in more detail below).

Because “impulsivity” can encompass a variety of definitions, consensus of what defines impulsivity is critical. Dalley, Everitt, and Robbins (2011, see recommended further reading) loosely defined impulsivity as the tendency to act prematurely without foresight. The clinical Barratt Impulsivity Scale measures impulsivity by self-report in categories of attention, motor action, and nonplanning. Preclinical laboratory behavioral measures focus on categories of impulsive action and impulsive choice (see Winstanley et al., in the section for further reading). These measures allow for investigation of whether the degree of impulsivity is a predictor of degree of later drug use. Indeed, in the case of self-administration in animal models of abuse, measurement of pre-drug impulsive choice and/or action correlates with subsequent alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine abuse. Further studies will be required to investigate whether this correlation extends as hypothesized to other drugs of abuse, as well as addictions beyond drugs of abuse.

A model proposed in 2011 by Dalley, Everitt, and Robbins (see further reading) posits that a propensity toward impulsivity leads to more compulsive drug-seeking following drug use. That is, an innate trait (impulsivity) may confer risk toward an inability to control the urge to obtain drug following protracted use, despite a conscious desire to abstain. The compulsive drive to obtain drug represents one of many deficits in decision-making and cognitive control associated with drug abuse across virtually all classes of drugs, described in detail in the following sections. Thus, the neurocircuitry and cellular substrates for this impaired ability are of considerable interest both for understanding common mechanisms of addiction and for identification of candidate avenues for pharmacotherapies. In this way, as in the case of impulsivity measures, animal models of drug dependence and drug-seeking provide invaluable tools by which to probe these mechanisms. While these models are discussed in detail in chapters throughout this edition, discussion of animal models of drug abuse are of merit here.

Relapse Vulnerability: Stress, Context, and Drug Cues

As discussed above, it could be difficult to differentiate behaviors as innate traits versus consequences of chronic drug use. Preclinical animal models are of particular use in delineating these, to allow for comparison of behaviors both before and after chronic drug use. Examples of noncontingent, experimenter-administered models of drug abuse include behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference (CPP). Behavioral sensitization reflects increased locomotor responsiveness to an acute drug challenge following a drug history, and CPP allows for comparison of preference for chambers associated with drug versus vehicle administration. While sensitization is largely a phenomenon observed in response to psychostimulants, CPP has been reported following exposure to virtually all drugs of abuse. These models are highly useful but lack an element of motivated drug-seeking.

One of the most widely utilized preclinical models of psychiatric conditions is the reinstatement model of addiction. In this model, animals are trained to self-administer a reinforcing drug of choice, typically for a period of a few weeks. Self-administration occurs via operant conditioning, in which an action (lever pressing, nose poke) results in an intravenous drug infusion, typically paired with the presentation of drug-paired cues (e.g. light and tone). Following the self-administration phase, an extinction period follows, in which lever pressing no longer results in drug or drug-paired cues. After a period of weeks of extinction training, during which operant responding declines to very low levels, reinstatement of lever pressing is achieved by presentation of a drug prime, reinstatement of drug-paired cues, reintroduction to drug environment, or a stressor. The relationship between stress and addiction is further discussed in Stress and Addiction. Reinstatement of lever pressing is designed to model relapse in the abstinent drug abuser, thereby allowing a means by which to study the mechanisms of relapse-related behaviors. These triggers for reinstatement have been validated for reinstatement to many drugs of abuse, including psychostimulants, opiates, nicotine, cannabinoids, and alcohol. Use of the reinstatement model of addiction allows for experiments designed to investigate the neurocircuitry and cellular mechanisms for drug-seeking behaviors and has proved fundamental to the current understanding of mechanisms of addiction.

Neurocircuitry of Addiction

Because the brain structures composing the limbic system are responsible for reward processing and learning reward associations, including the perception of reward by drugs of abuse, drug abuse is increasingly considered to represent a maladaptive engagement of reward processing. Thus, engagement of neural nuclei responsible for reward processing is believed to represent a common mechanism of addiction to drugs of abuse.

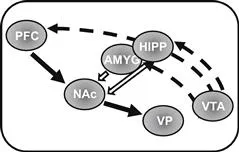

The immediate rewarding effects of drugs of abuse (as for natural rewards) are in large part mediated by a rapid and robust increase in dopamine (DA) transmission from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to structures in the corticolimbic system, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala, and hippocampus (Fig. 17.1).

FIGURE 17.1 Basic neurocircuitry of addiction. Dopaminergic projections (dashed arrows) from the VTA form connections predominantly to the PFC, hippocampus (HIPP), amygdala (AMYG), and NAc. Glutamatergic projections (solid arrows, filled and open) are sent from the HIPP, AMYG, and PFC to the NAc. The solid arrow from NAc to VP represents GABAergic projections. The common final pathway (PFC to NAc to VP) is indicated by solid filled arrows. Note: shown here is a basic circuitry relevant to discussion of common mechanisms of addiction. More detailed discussion of other structures, which contribute to addiction-related behaviors, may be found in the recommendations for further reading, in particular Koob and Volkow (2010) and Kalivas and Volkow (2005).

Activation of the VTA is a common feature of the reinforcing effects of virtually all drugs of abuse, discussed in more detail in the following section. Following extended substance ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Editors: Biographies

- List of Contributors

- Section I: Behavioral Biology, Preclinical Animal Studies of Addiction

- Section II: Neuroscience

- Section III: Genetics

- Section IV: Neuropharmacology/Imaging/Genetics

- Index