eBook - ePub

Informatics for Materials Science and Engineering

Data-driven Discovery for Accelerated Experimentation and Application

- 542 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Informatics for Materials Science and Engineering

Data-driven Discovery for Accelerated Experimentation and Application

About this book

Materials informatics: a 'hot topic' area in materials science, aims to combine traditionally bio-led informatics with computational methodologies, supporting more efficient research by identifying strategies for time- and cost-effective analysis.

The discovery and maturation of new materials has been outpaced by the thicket of data created by new combinatorial and high throughput analytical techniques. The elaboration of this "quantitative avalanche"—and the resulting complex, multi-factor analyses required to understand it—means that interest, investment, and research are revisiting informatics approaches as a solution.

This work, from Krishna Rajan, the leading expert of the informatics approach to materials, seeks to break down the barriers between data management, quality standards, data mining, exchange, and storage and analysis, as a means of accelerating scientific research in materials science.

This solutions-based reference synthesizes foundational physical, statistical, and mathematical content with emerging experimental and real-world applications, for interdisciplinary researchers and those new to the field.

- Identifies and analyzes interdisciplinary strategies (including combinatorial and high throughput approaches) that accelerate materials development cycle times and reduces associated costs

- Mathematical and computational analysis aids formulation of new structure-property correlations among large, heterogeneous, and distributed data sets

- Practical examples, computational tools, and software analysis benefits rapid identification of critical data and analysis of theoretical needs for future problems

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Informatics for Materials Science and Engineering by Krishna Rajan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Materials Informatics

An Introduction

Krishna Rajan, Dept. of Materials Science & Eng. and Bioinformatics & Computational Biology Program – Iowa State University, Ames IA, USA

1 The What and Why of Informatics

The search for new or alternative materials or processing strategies, whether through experiment or simulation, has been a slow and arduous task, punctuated by infrequent and often unexpected discoveries. Each of these findings prompts a flurry of studies to better understand the underlying science governing the behavior of these materials. While informatics is well established in fields such as biology, drug discovery, astronomy and quantitative social sciences, materials informatics is still in its infancy. The few systematic efforts that have been made to analyze trends in data as a basis for predictions have in large part been inconclusive, not least of which is due to the lack of large amounts of organized data and even more importantly the challenge of sifting through them in a timely and efficient manner.

When combined with a huge combinatorial space of chemistries as defined by even a small portion of the periodic table, it is clearly seen that searching for new materials with tailored properties is a prohibitive task. Hence the search for new materials for new applications is limited to educated guesses. Data that does exist is often limited to small regions of compositional space. Experimental data is dispersed in the literature and computationally derived data is limited to a few systems for which reliable data exists for calculations. Even with recent advances in high-speed computing, there are limits to how the structure and properties of many new materials can be calculated. Hence this poses both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is to deal with extremely large disparate databases and large-scale computation. It is here that knowledge discovery in databases or data mining, an interdisciplinary field merging ideas from statistics, machine learning, databases, and parallel and distributed computing, provides a unique tool to integrate scientific information and theory for materials discovery. The key challenge in data mining is the extraction of knowledge and insight from massive databases. It takes the form of discovering new patterns or building models from a given data set. The challenge is to take advantage of recent advances in data mining and apply them to state-of-the-art computational and experimental approaches for materials discovery.

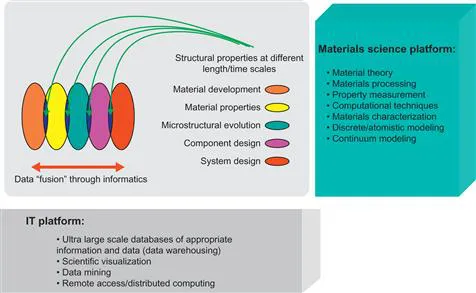

A complete materials informatics program will have an information technology (IT)-based component that is linked to classical materials science research strategies. The former includes a number of features that help informatics to be critical in materials research (Figure 1.1):

• Data warehousing and data management: This involves a science-based selection and organization of data that is linked to a reliable data searching and management system.

• Data mining: Providing an accelerated analysis of large multivariate correlations.

• Scientific visualization: A key area of scientific research that allows high dimensional information to be assessed.

• Cyber infrastructure: An information technology infrastructure that can accelerate the sharing of information, data, and most importantly knowledge discovery.

Figure 1.1 The role of materials informatics is pervasive across all aspects of materials science and engineering. The mathematical tools based on data mining provide the computational engine for integrating materials science information across length scales. Informatics provides an accelerated means of fusing data and recognizing in a rapid yet robust manner structure–property relationships between disparate length and time scales. (From Rajan, 2005.)

2 Learning from Systems Biology: An “Omics” Approach to Materials Design

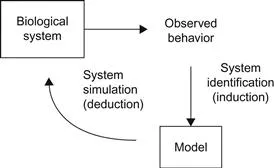

The concept of complexity in biology and how to assess the links between information at the molecular level to that at the living organism level (e.g. genomics, proteomics, etc.) is the foundation of systems biology. The understanding of systems biology provides an excellent paradigm for the materials scientist. Ultimately one would like to take an “atoms applications” approach to materials design. How do we organize atoms and build systematically structural units at increasing length scales to ultimately the final engineering component or structure? At present we need to rely on extensive prior knowledge with experiments, computation, and ultimately even failure analysis to understand the complex network of interactions of materials behavior that govern the performance of an engineering system. The problem is that even with advanced experimental and computational tools, the rate of discovery is still slow, only punctuated by unexpected findings (e.g. superconducting ceramics, conducting polymers) that stimulate new areas of research and development. The iterative approach as shown in Figure 1.2 is common to many fields as one tries to link observations with models. The challenge is to develop models that capture the system behavior by accounting for all the different levels of information that contribute to the system’s behavior.

Figure 1.2 Logic of information flow and and knowledge discovery in classical research methodology. The example provided here addresses the use of qualitative reasoning to simulate and identify metabolic pathways. (From King et al., 2005.)

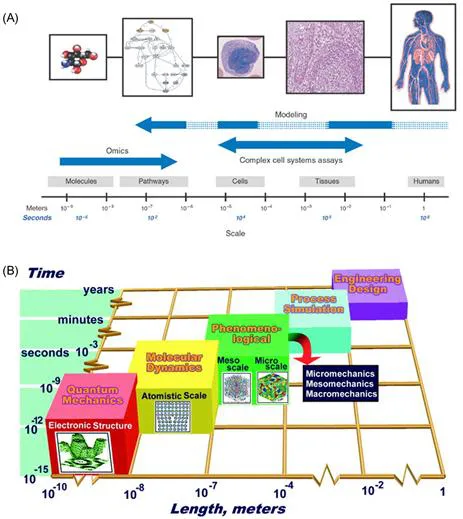

The goal of modern systems biology is to understand physiology and disease from the level of molecular pathways, regulatory networks, cells, tissues, organs and ultimately the whole organism (Butcher et al., 2004). As currently employed, the term “systems biology” encompasses many different approaches and models for probing and understanding biological complexity, and studies of many organisms from bacteria to man. A similar paradigm exists for materials, e.g. atoms to airplanes (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Comparison of length scale challenges in designing drugs for the life sciences (a; from Butcher et al., 2004) and designing materials for the engineering sciences (b; from Noor et al., 2000). Note the overlap in the length scales that govern engineering design/human body.

As aptly described by Butcher et al., the “omics” (the bottom-up approach) focuses on the identification and global measurement of molecular components. Modeling (the top-down approach) attempts to form integrative (across scales) models of human physiology and disease although, with current technologies, such modeling focuses on relatively specific questions at particular scales, e.g. at the pathway or organ levels. An intermediate approach, with the potential to bridge the two, is to generate profiling data from high-throughput experiments designed to incorporate biological complexity at multiple levels: multiple interacting active pathways, multiple intercommunicating cell types, and multiple different environments.

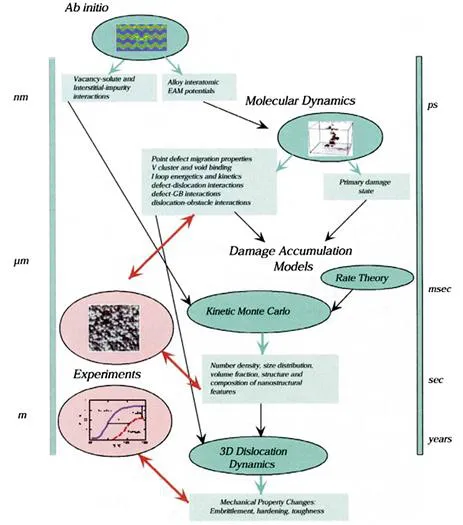

A similar challenge occurs in materials science, identifying pathways of how chemistry, crystal structure, microstructure, processing variables, and component design and manufacturing “communicate” with each other to ultimately define performance. This forms the materials science equivalent of the biological regulatory network (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 An example of a “regulatory network” linking diverse sets of information from both theory and experiment in the study of materials degradation due to irradiation. (From Wirth et al., 2001.)

Because biological complexity is an exponential function of the number of system components and the interactions between them, and escalates at each additional level of organization (Figure 1.5), such efforts are currently limited to simple organisms or to specific minimal pathways (and generally in very specific cell and environmental contexts) in higher organisms. The same can be said of complexity in materials science.

Figure 1.5 Identification of regulatory pathways using network graphing and simulated annealing methods. (This figure has been reprinted from Ideker et al., 2002, by permission of Oxford University Press, and Aitchison and Galitski, 2003.)

Even if our ability to measure molecules and their functional states and interactions were adequate to the task, computational limitations alone would prohibit our understanding of cell and tissue behavior at the molecular level. Thus, methodologies that filter information for relevance, such as biological context and experimental knowledge of cellular and higher level system responses, will be critical for successful understanding of different levels of organization in systems biology research.

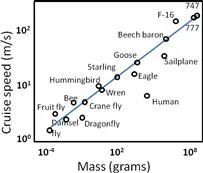

Informatics is the enabling tool to facilitate this process. For instance, Csete and Doyle (2002) have provided a very appropriate analog between biological and engineering systems that can help to put materials informatics in perspective. A striking example of converging information across length scales is shown in Figure 1.6, where one is comparing cruise speed to mass M over 12 orders of magnitude, from 747 and 777, to fruit flies. This provides a good example of how, if one can integrate and identify key metrics (data), functional relations between variables across many scales can be developed. Here, a well-known elementary argument shows good correspondence with the data and yields explanations for deviations.

Figure 1.6 A scaling diagram of design behavior or aeronautical systems (both biological and artificial). (Adapted from Csete and Doyle, 2002.)

Such theories are largely irrelevant to complexity directly, but an understanding of them leads to what is relevant. The scaling theory described by the above figure does not distinguish between flight in the atmosphere and in a laboratory wind tunnel. In the latter context, a much simpler “mutant” 777 with nearly all of its 150,000-count “aeronome” knocked out would have roughly the same lift, mass, and cruise speed, and thus (from an allometric scaling viewpoint) would exhibit no deleterious laboratory “phenotype”. Redundancy does not explain this finding. Rather, the mutant has lost control systems and robustness required for real flight outside the lab. Allometric scaling emphasizes the essentia...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface: A Reading Guide

- Acknowledgment

- Chapter 1. Materials Informatics: An Introduction

- Chapter 2. Data Mining in Materials Science and Engineering

- Chapter 3. Novel Approaches to Statistical Learning in Materials Science

- Chapter 4. Cluster Analysis: Finding Groups in Data

- Chapter 5. Evolutionary Data-Driven Modeling

- Chapter 6. Data Dimensionality Reduction in Materials Science

- Chapter 7. Visualization in Materials Research: Rendering Strategies of Large Data Sets

- Chapter 8. Ontologies and Databases – Knowledge Engineering for Materials Informatics

- Chapter 9. Experimental Design for Combinatorial Experiments

- Chapter 10. Materials Selection for Engineering Design

- Chapter 11. Thermodynamic Databases and Phase Diagrams

- Chapter 12. Towards Rational Design of Sensing Materials from Combinatorial Experiments

- Chapter 13. High-Performance Computing for Accelerated Zeolitic Materials Modeling

- Chapter 14. Evolutionary Algorithms Applied to Electronic-Structure Informatics: Accelerated Materials Design Using Data Discovery vs. Data Searching

- Chapter 15. Informatics for Crystallography: Designing Structure Maps

- Chapter 16. From Drug Discovery QSAR to Predictive Materials QSPR: The Evolution of Descriptors, Methods, and Models

- Chapter 17. Organic Photovoltaics

- Chapter 18. Microstructure Informatics

- Chapter 19. Artworks and Cultural Heritage Materials: Using Multivariate Analysis to Answer Conservation Questions

- Chapter 20. Data Intensive Imaging and Microscopy: A Multidimensional Data Challenge

- Index